"Throw down your arms, ye villains, ye Rebels, Disperse!"

by Dennis Montgomery

Online Extra

Sidebar: Fields of Fire—Four Views of the Fatal Day

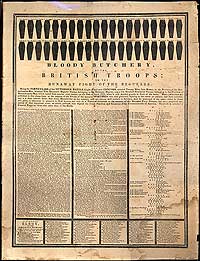

This coffin-ranked Salem, Massachusetts, broadside reported the Americans' overheated version of the fighting and events of April 19, 1775. It exists in at least two contemporary forms and in commemorative facsimiles.

You remember the Shot Heard 'Round the World. It was fired when a few New England minutemen, roused from their beds by a hard-riding Boston silversmith, mustered at Lexington—or was it Concord?—one brave morning, shouldered their muskets, and faced down a troop of marauding redcoats.

Not exactly.

"Not exactly" was an expression still fashionable during my high-school years in small-town, 1960s West Tennessee, an epoch as remote as was the place, a time when the textbook The United States: Story of a Free People taught:

In April 1775, General Gage, the military governor of Massachusetts sent out a body of troops to take possession of military stores at Concord, a short distance from Boston. At Lexington, a handful of "embattled farmers," who had been tipped off by Paul Revere, barred the way. The "rebels" were ordered to disperse. They stood their ground.As far as they go, some points of that paragraph are accurate, just not all the important ones. Look at the Paul-Revere, the embattled-farmers-barring-the-way, and the stood-their-ground stuff.

Not exactly.

Accounts of what happened that day went doubtful before the gunsmoke lifted. Contradiction bedeviled eyewitness relations. No one knows now precisely what happened, or why, and few knew then. The Boston News-Letter said:

The reports concerning this unhappy affair, and the causes that concurred to bring on an engagement, are so various, that we are not able to collect anything consistent or regular, and cannot therefore with certainty give our readers any further account of this shocking introduction to all of the miseries of a Civil War.Consider the fracas at Concord's North Bridge—the second skirmish of April 19. The object of the redcoats' march was a cache of banned military stores at that town, where the Provincial Congress had been sitting.

General Thomas Gage occupied Boston, a port closed in retaliation for its Tea Party. The crown had abolished the colony's government, the congress was extralegal, and its in-your-face war preparations were rebellious. With mixed success, and infuriating the already sulky Massachusetts men, Gage had staged similar raids in the countryside. This was but another, and not much of a surprise, either.

When his army column, about 800 soldiers strong and commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Francis Smith, arrived, the colonials had hidden most of the stores thanks to a warning Revere provided not at the end of his Midnight Ride but during a canter three days before. He knew Sunday the British were coming; he just couldn't say it would be Wednesday. Revere passed the word that sabbath to John Hancock, the congress's president, who was staying in Lexington, four or five miles from Concord, with his kinsman the Reverend Mr. Jonas Clarke, along with Samuel Adams, the legislature's secretary. Hancock passed the word to Concord, and Revere went home. On his way, Revere arranged the "one if by land, two if by sea" signal.

This patriotic portrayal of the Lexington fight gives defiant Americans the better end of the engagement. Engraved in the 1790s by Cornelius Tiebout after a Elkanah Tisdale rendering.

Before Smith marched, Concord Tories told Gage where they thought the stores were moved, but the soldiers found little. Smith settled for toppling the town's liberty pole, knocking the trunions off three iron cannons, digging up a brass gun at the gaol, and throwing barrels of flour and 5,000 musket balls into Concord River. He burned gun carriage wheels, and wooden trenchers and spoons, and he was done.

Smith's troops tried to avoid collateral damage. His officers paid for their tavern breakfasts, and his soldiers refrained from searching places from which residents shooed them. If a building or two had not accidentally taken fire—blazes a bucket brigade of Regulars and townspeople doused—Smith might have gotten away unmolested.

But about 400 militiamen watching from a hill got to worrying he was burning all Concord, charged their muskets, and went down to see—under orders not to fire first.

It was about 10 a.m. Before them was North Bridge, guarded by 120 Regulars—maybe 200—commanded by Captain Walter Laurie, detailed to protect the span while other redcoats searched woods and farms for the hidden stores. Concord's green spread about a mile beyond. The militia had to cross the bridge to get into town. Laurie, retreating to the Concord side, gave orders to pull up the planks, but none to shoot, and put his men into formation.

He reported, "I imagine myself, that a man of my Company (afterwards killed) did first fire his piece," but his comrade, Lieutenant William Sutherland, "has since assured me, that the Country people first fired." Other witnesses, however, blamed Laurie's dead man, too.

Ralph Waldo Emerson, in "The Concord Hymn," credited "the shot heard round the world" to "embattled farmers." If he meant by that the opening shot of the Revolution, he was mistaken. As we shall see, this was not, by a long shot, the first of the day. Moreover, Laurie's soldiers were the only men "barring the way" of anyone, and it is hard to see that anyone but they, outnumbered at least two to one, are properly describable as embattled. But Emerson wrote in 1837, when time had washed away the bridge and watered down interest in historical verisimilitude.

After whoever pulled his trigger first, militia Major John Buttrick shouted, "Fire fellow soldiers, for God's sake, fire," and muskets rattled on either side. Before the redcoats broke, two miltiamen were dead, as were two Regulars. A provincial later hatcheted to death a wounded Regular sprawled on the ground.

Buttrick's rebels pursued Laurie until Regular reinforcements sallied from town. The farmers retreated, and resumed eyeballing Smith. About noon, having assembled carriages for his wounded, Smith put his men on the road back to Boston with little to show for his time but starting a war—hours before at Lexington.

Artist Grant Wood, better known for his American Gothic painting, took a surrealistic, vaguely forbidding view of "The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere."

Just as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote eighty-five years later in "The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere," "on the eighteenth of April, in Seventy-five" the Boston patriot's "cry of alarm" reached "every Middlesex village and farm." But Revere never got to Concord that night, and, anyway, an alarm was out by the time he reached Lexington.

News that the Regulars were up to something had twice that evening reached Lexington, which straddles the road to Concord, when Revere rode in. It came from the Cambridge committee of safety, which said a patrol of eight or nine British officers was on the way. Clarke suspected them of "some evil design," probably, he thought, the arrest of his guests Hancock and Adams. The Lexington militia set a guard around Clarke's house.

When Smith, about 10 p.m., began to ferry troops—twenty-one companies in boats across the Charles River from Boston to Cambridge—rebel sparkplug Dr. Joseph Warren dispatched Revere with a warning, after sending tanner William Dawes on the same errand by another route.

Revere got to Lexington before Dawes, about midnight, by which time, the British officers, who seem to have been reconnoitering, had passed on the Concord road. Not to shortchange Revere: he brought first word that 800 more soldiers were coming.

Before Smith had his troops on the march—there were delays—the countryside had heard of their approach, and Smith knew it. Alarm guns and bells sounded. Beacon fires burned. Smith's errand was bootless before it began. He might as well have turned back before someone got hurt.

Lexington's militia captain, John Parker, forty-five, a Roger's Ranger in the French and Indian War, said he learned about 1 a.m. that Regular officers were stopping colonials on the road and was "informed that a number of the regular troops were on their march from Boston" in order to take the provincials' stores at Concord. Parker said he

ordered our militia to meet on the common in Lexington, to consult what to do, and concluded not to be discovered nor meddle nor make with said regular troops (if they should approach) unless they should insult or molest us, and upon their sudden approach, I immediately ordered our militia to disperse and not to fire. Immediately said troops made their appearance and rushing furiously, fired upon and killed eight of our party, without receiving any provocation therefor from us.

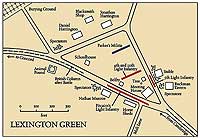

A map of the forces at Lexington when the Revolution began shows Parker's militia, the blue line, was in no position to block the redcoat march. Pitcairn divided his force, the red lines, to disperse the Americans rather than leave armed men to his rear.

Parker's account telescopes two miltia musters that night. The first was about 1 a.m. When no Regulars showed, Parker, supposing a false alarm, dismissed his men, subject to the recall of the drum. Revere left for Concord and rode into the grasp of the reconnoitering Regular officers. Another rider carried the warning to Concord. The second muster was just before dawn.

Smith's orders said nothing about arresting Hancock or Adams, or stopping in Lexington. Anyway, Hancock and Adams decided to skedaddle before Smith arrived, and Lexington had nothing left of interest to the redcoats for Parker's men to bar the way to. They might as well have gone back to bed.

Scouts and others began running into an advance redcoat contingent, six light infantry companies led by marine Major John Pitcairn. Pitcairn's orders were to hurry through Lexington to secure Concord's bridges for Smith's slower grenadiers. At about 4 a.m., outside Lexington, Pitcairn surprised two or three rebels. Lieutenant Sutherland rode up with Lieutenant Jesse Adair. A fleeing provincial turned and shot. The musket charge did not detonate. The first shot of the Revolution was a flash in the pan.

Pitcairn ordered his men to load their weapons but "on no account fire or even attempt it, without orders" and to proceed at double time in double ranks. Lexington knew now Pitcairn was close. At about 4:30 a.m., drummer William Diamond was beating Parker's recall. Men—none of them minutemen, just militiamen—were tumbling out of taverns and homes to form on the green. Clarke said:

The commanding officer thought best to call the company together,—not with any design of the commanding officer opposing so superior a force, much less of commencing hostilities; but only with a view to determine what to do, when and where to meet, and to dismiss and disperse.There were perhaps seventy-seven of them, maybe thirty-eight in ranks, when Pitcairn came up. They were out the way, well off the Concord road to Pitcairn's right, on the triangular green, a stone wall behind them. They had a right to be there, but no particular purpose, and they stood in harm's way. Pitcairn could not troop by and leave an armed force to his rear, which the veteran Parker should have realized. Pitcairn turned, detached two parties, and advanced.

Witnesses said Parker shouted, "The first man who offers to run shall be shot down," and, "Stand your ground. Don't fire unless fired upon. But if they want to have a war, let it begin here." Not exactly. Parker swore the contrary. Clarke, too.

"The rude bridge that arched the flood" at Concord—a picture of a commemorative replacement above—was the subject of Ralph Waldo Emerson's poem "The Concord Hymn," written for celebrations July 4, 1837.

About then, Pitcairn yelled, "Disperse, ye rebels, disperse," or "Lay down your arms, you damned rebels, and disperse," or "Throw down your arms, ye villains, ye Rebels." Most of those rebels were already scrambling to get out of the way. Fifty signed a deposition saying: "Whilst our backs were turned on the troops, we were fired on by them. . . ."

Pitcairn reported:

They began to file off towards some stone walls on our right flank. The Light Infantry, observing this, ran after them. I instantly called to the soldiers not to fire, but surround and disarm them, and after several repetitions of those positive orders to the men, not to fire, etc. some of the rebels who had jumped over the wall fired four or five shots at the soldiers, which wounded a man ...and my horse was wounded in two places ...and at the same time several shots were fired from a meeting house on our left.

Warren, to fix first-fire blame on the redcoats, collected depositions from participants and witnesses in the next eight days. Some thought the shot came from a Regular officer's pistol. Some thought a Regular officer gave the order to fire. It may be that a weapon discharged by accident. No one on either side owned up to any shot heard round the world.

Some of Smith's officers, knowing Concord would be warned once more, and saying it really was feckless to continue now, urged him to turn about for Boston's barracks. But Smith had his orders. The troops gave three huzzahs, discharged a victory volley, and struck off.

When their Concord work was done, Smith's soldiers had to retrace their route through a hornet-hot countryside. On the way back to Lexington, the militia, ranks growing by the minute, ambushed the Regulars four or five times. Thirty-one redcoats were killed. The rest broke and ran, halted by officers who got in front and turned with bayonets fixed.

A relief column of 1,000 Regulars, led by General Hugh, Earl Percy, and pulling two six-pound cannons from Boston, met them, hours late, at Lexington and saved a rout. But the Regulars had to pass a fifteen-mile gauntlet of angry colonials to Cambridge and the Charles for the boats to Boston. About 3,600 provincials came out to kill them. Regular Lieutenant Robert MacKenzie wrote:

We were fired at from all quarters, but particularly from the houses on the roadside, and the Adjacent Stone walls. Several of the Troops were killed and wounded in this way, and the soldiers were so enraged at suffering from an unseen Enemy, that they forced open many of the houses from which the fire proceeded, and put to death all those found in them.Smith lost 73 dead, 174 wounded, 26 missing; the rebels 49 dead, 39 wounded, and 5 missing. The Americans broke off the engagement near Cambridge.

Word of the fighting reached Williamsburg ten days later, relayed from Philadelphia, in a collection of fragmentary, garbled, and doubtful communiqués. One thing, at least, was certain.

As the last report said: "It is now full time for us all to be on our guard, and to prepare ourselves against every contingency. The Sword is now drawn, and God knows when it will be sheathed."

Dennis Montgomery contributed to the October-November 1999 journal the story "The World Turned Upside Down," the song the British probably didn't play when they surrendered at Yorktown six years after these events.

Suggestions for further reading:

- Jonas Clark, A Sermon Preached at Lexington, April 19, 1776 ...to Which is Added a Brief Narrative of the Principal Transactions of that Day (Boston, 1776)

- David Hackett Fischer, Paul Revere's Ride (New York, 1994)

- Allen French, The Day of Concord and Lexington (Boston, 1925)

- Massachusetts Provincial Congress, A Narrative of the Excursion and Ravages of the King's Troops (Worcester, MA, 1775)

- Arthur Bernon Tourtellot, Lexington and Concord: The Beginning of the War of American Revolution (New York, 1959)