Page content

Taking the Cure

Colonial Spas, Springs, Baths, and Fountains of Health

by Harold B. Gill Jr.

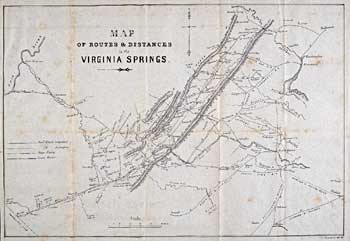

J. J. Moorman’s 1859 map showed travelers how to reach Virginia’s springs by railroad, stagecoach, horseback or canal.

-Colonial Williamsburg

In August of 1818, bedeviled by his rheumatism and his seventy-five years, Thomas Jefferson picked his way up into the Appalachians to take the Warm Springs waters. There, where Warm Springs Run clefts Little Mountain and spills into the Warm Springs Valley, the ex-president sat in the geothermally heated mineral waters three times a day for three weeks, trying to soak away his pain. But the treatment little mended his complaints, and the seating seems to have raised boils on his buttocks. On the way home to Monticello, his own little mountain, the sores reduced him, writes biographer Dumas Malone, “to the lowest state of debility.”

Jefferson was not the first to try the opinion that Virginia’s springs were fountains of health, nor the last to come away with second thoughts. Native Americans had been seeking cures in the waters for centuries, likely with results as mixed, and the tired and the infirm still repair to the soothing pools looking for relief.

That so many return may be because the springs have long attracted people for more than their medicinal powers. Scattered down the ribs of Virginia’s westernmost mountains, the springs are resorts of the well-to-do and the fashionable escaping the humid summer seaboard heat. Even before Jefferson’s day, the better sort gathered at the waters for good accommodations, good company, and good food. He noted a “table very well kept by Mr. Fry,” his host. “Venison is plenty, and vegetables not wanting.” And he was disappointed because there was “but little gay company here at this time, and I rather expect to pass a dull time.”

The belief that drinking and bathing in mineral waters are sure cures for human ailments has been common for centuries. Archaeological excavations at Bath, England, revealed that humans have enjoyed those mineral springs for at least 10,000 years. Virginia is blessed with a string of natural warm mineral baths, most tucked in the folds of the mountains that rise beyond the Shenandoah Valley. In his Notes on the State of Virginia, Jefferson wrote, “There are several medicinal springs, some of which are indubitably efficacious, while others seem to owe their reputation as much to fancy and change of air and regimen, as to their real virtues.”

Sometimes, their names were as unsettled as the understanding of their efficacy. Berkeley Springs, in what became Morgan County, West Virginia, was the first of Virginia’s warm springs to gain popularity. When George Washington first visited them in March 1748 while on a surveying expedition, they were called Warm Springs—not to be confused with old Augusta Warm Springs, the modern Warm Springs—about 130 miles southwest.

Near the borders of Pennsylvania and Maryland, they were already so frequented that Washington called them the “Fam’d Warm Springs.” But other spas had enthusiastic clientele, too. When in 1750 Dr. Thomas Walker visited Hot Springs, about 135 miles southwest, he found six invalids enjoying water “clear and warmer than new milk.”

Washington returned to old Warm Springs in 1761 in hopes of a cure for rheumatic fever. After a day, he thought his “fevers a good deal abated though my pains grow rather worse and my sleep equally disturbed.” When he arrived he found about 200 people “full of all manner of diseases and complaints; some of which are much benefited, while others find no relief from the waters.”

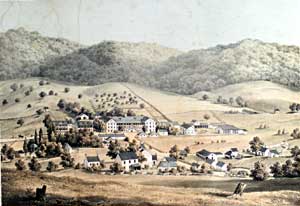

-College of William and Mary

German artist Edward Beyer’s lithograph captured the ambience of Virginia’s Warm Springs in the 1850s.

He came back in July 1769 with his wife and stepdaughter, Patsy Custis. They made the trip to see whether water would help in Patsy’s battle with epilepsy. They found the place crowded with such people as Lord Fairfax, Colonel George Fairfax, Warner Washington, James Wood, and visitors from New Jersey, Annapolis, and Alexandria. The Washingtons stayed until September 9, apparently without any substantial improvement in Patsy.

In August 1775, Philip Vickers Fithian, a traveling minister, stopped and found roughly 400 people, about half of them “visibly indisposed.” He met “Mr. Diggs of York . . . the Picture of Decrepitude.” He said Edward Biddle, “one of the Delegates for the Province of Penn. in the Con Congress is here & much disordered with the Rheumatism.”

Fithian noted that while a “splendid Ball” was in progress, “at some Distance & within hearing, a Methodist Preacher was haranguing the People. . . . In our dining Room Companies at Cards, Five & forty, Whist, Alfours, Callico-Betty &c. I walked out among the Bushes here also was—Amusements in all Shapes, & in high Degrees, are constantly taking Place among so promiscuous Company.” The waters, it seems, had special powers after all.

The next day Fithian recorded:

From twelve to four this Morning soft & continual Serenades at different Houses where the Ladies lodge. Several of the Company, among many the Parson, were hearty. Miss ——— said to be possess’d of an Estate in Maryland of ten thousand Pounds is accused by the Bloods as imperious & haughty. An Accusation against one ——— for breaking, in the Warmth of his Heart, through the Loge & entering the Lodging Room of buxom Kate ———. Unfortunate Scot, he was led to this immediately stimulated by a plentiful Use of these Vigor-giving Waters. He came to recruit his exhausted System. He was urged—he was compell’d, by the irresistable Call of renewed Nature.

No wonder the springs were popular.

The Virginia legislature, seeing the possibilities, renamed the place “Bath,” expecting it to become Virginia’s answer to Bath, England. The name was changed later to Berkeley Springs. A historian wrote in 1833 that the Berkeley Springs “are much resorted to, not only for their value as medical waters, but as a place (in the season) of recreation and pleasure.”

Warm Springs or Bath or Berkeley Springs began to lose some of its attraction when people realized that Augusta Springs—today’s Warm Springs—was warmer. The springs at Bath were about 76° Fahrenheit; at Augusta Springs about 97° Fahrenheit and Hot Springs about 120°. Jefferson said the waters at Augusta Warm Springs were the most efficacious. He thought Berkeley Springs “are more visited, because situated in a fertile, plentiful, and populous country, better provided with accommodations, always safe from the Indians, and nearest to the more populous States.”

-College of William and Mary

White Sulphur Springs, another Beyer subject, was renowned for its healing powers and then for its social attractions.

In January 1776, on his way to the Greenbrier settlements, Fithian was halted by bad weather at Augusta Warm Springs, as he called it. He recorded in his journal:

The Waters rise in several Parts boiling in windy Bubbles perpendicularly from the Ground—in the bathing Spring the Place of rising is nearly twelve Feet Square; much Water rises.

The Water is perfectly clear; not a Mote to be seen: It smells, & tastes strongly like the Washings of a foul Gun—But its distinguishing Quality, & to me exceeding surprizing, is its Warmth—Now it is quite as warm a Fluid as I should be willing to hold my Hand in for any Time longer than a Minute—If it was hotter it would give me Pain! A Fog of Smoke rises from off it as from a Coal Kiln—I drank almost a Pint of the Water; I could not drink more; I washed my Face & Hands, this was pleasant—It is not safe at this Season to bathe—.

The Place of bathing is enclosed with a strong Stone Wall I think thirty Feet diameter, in an octagonal Form; the Water is between three & four Feet deep, which make a commodious Place for bathing.

Its chief Uses are for Sores & Pains!

The men’s bathing pool at Warm Springs, unusual for its circular shape, shares the spring that feeds this stream.

-Dave Doody

When John Howell Briggs of Sussex County visited in July 1804, he found indifferent accommodations and indifferent food. Yet, he said, “the bath at the Warm Springs is most luxurious. It is inclosed with an octangular wall; about ten yards across and in the center about 5 feet 6 inches deep, shallower at the sides.”

Fithian was told that between two hundred and three hundred people visited these springs annually, and he believed “its Fame is not more extended” because the “Distance between them & the lower Settlements is so great; & the Road so mountainous & stoney; & the little Leasure which the greatest Number of the Americans yet have.” To make Augusta Warms Springs more easily accessible, a “good Coach-Road” had been built over Warm Spring Mountain. On it, Fithian found, “you may gallop a Horse, and not hurt him or yourself,” from one side to the other.

From the 1790s the mineral springs of Virginia developed into full-scale summer resorts, well on their way to becoming America’s premier vacation spots, attracting fashionable crowds from throughout the nation. The most popular season was July and August, when the gentry from the hot eastern and southern regions flocked to the rustic mountain spas. In 1791 Ferdinand-M. Bayard, a French visitor to Berkeley Springs, wrote:

In the United States, as in Europe, the watering-places are not visited by the sick alone; to them are attracted the healthiest and the most robust in search of pleasure and love; but in America, the unwholesome air of the cities, during the excessive heat of dog-days, is an additional reason for going there. The months of June, July and August are fatal to children: mature age fears their dangerous influence, and everyone seeks the freshness of the woods and mountains, and a purer air.

Most nineteenth-century spa goers visited several springs on their summer jaunts. The owners of each claimed their waters had special benefits for certain ailments. But the main attractions were amusement and socializing. The first stop was usually at Augusta Warm Springs. From there guests traveled on to Hot Springs and White Sulphur Springs, about thirty-three miles southwest, in modern West Virginia.

By virtue of its elegance, White Sulphur Springs became known as the “Queen of the Springs.” After spending a week or two at the White Sulphur, visitors usually went to Sweet Springs for a stay. Jefferson believed Sweet Springs, in Botetourt County, relieved ailments “in which the others had been ineffectually tried.”

Colonel John Fry, the innkeeper at Warm Springs, advised his guests to go “and get well charged at the White Sulphur, well salted at the Salt, well sweetened at the Sweet, well boiled at the Hot and then let them return to him and he would Fry them.” Fry was renowned for his hospitality, and the Warm Springs Hotel was noted for its excellent food and superior bathing facilities. A Baltimore lawyer, John H. B. Latrobe, said that “the Warm Springs are free and easy” and White Sulphur was noted for its “Etiquette.”

John Howell Briggs visited White Sulphur in 1804. “Tho’ there was a great deal of genteel Company here of both sexes,” he wrote, “yet I left this place, with great pleasure—for the number of invalids, afflicted with various diseases, with limbs distorted by pain, and unable to assist themselves, who were here in hopes of relief, or a mitigation of their torments, rendered an abode here, very unpleasant, to a man of feeling, unaccustomed to such scenes.”

The original Warm Springs women’s bathing pool, larger than the men’s, dates to 1836.

-Dave Doody

White Sulphur Springs reached its greatest popularity in the second decade of the nineteenth century, when James Calwell became sole proprietor. He had owned one-seventh of the White since 1795. White Sulphur Springs drew crowds even though until 1790 it could be reached only on horseback along old Indian trails. Once a road was cut through the forest, Calwell built his first lodging house. A close friend of Henry Clay, he was criticized by some because he admitted only patrons who met his high standards of conduct, but he was generally respected and was a pleasant companion.

Calwell improved the buildings, constructing a hotel and cabins and allowing private cottages. According to one visitor, the buildings at White Sulphur Springs emerged from “no plan, but bit by bit as there was need to enlarge the accommodations.” The only architect known to have planned structures at the White was the aforementioned lawyer, John H. B. Latrobe, son of Benjamin Latrobe, who designed Baltimore Row about 1830.

Calwell was noted for providing lavish entertainment in the grand ballroom. When Blair Bolling visited in 1838, he found President Martin Van Buren, the secretary of war, and “many other distinguished individuals.” The evening ended, Bolling reported, “with the usual Ball where there was a good display of Beauty and plenty of fine dressed individuals, some arogance, but upon the whole, quite an agreeable entertainment for the young and gay, as well as many of riper years.”

The guest lists included wealthy planters from Baltimore to New Orleans, but Virginians predominated. In 1833, a Philadelphia visitor said Virginians set the tone at the Springs, “distinguished by the excellence and polish of its company.” He said: “Whatever Virginia has of wealth, talent, personal elegance, or professional eminence, finds itself represented, and by a proper combination forms a gay and highly finished aggregate.”

Bolling described the place thusly:

The White Sulphur spring is covered by a circular Dome or Temple supported by twelve collumns of the planest order, a little defective in architectual proportion, being rather too tapering, upon the centre of which Dome, is a statue surmounted upon a double pedestal also circular in form, the topmost one the smallest, have the word HYGEA inscribed on its edge in guilt letters and the following inscription upon the side of the bottom, “Presented by S Henderson Esqr of New Orleans” it represents a human figure as large as life with a serpant coiled around the left arm and with a bowl in her right hand, signifying that the virtue of the water of that fountain can render harmless the wound inflicted by the bite even, of a venomous serpant and so gratful was this liberal donor on account of the benifit that he had received from the use of those waters that he not only made that handsom present to the Proprietor but had a handsom building erected on an emminence that is call the Pallase and is at present occupied by Martin Van Buren, President of the United States while on a tour, in quest of health Pleasure or Popularity but most probibly the latter.

Calwell put the administration of White Sulphur Springs in the hands of his majordomo, Major Baylis Anderson, whose main responsibility was assigning accommodations. With a single word, Anderson would admit or refuse any guest to the most sought-after spa in the South. He was, at least during the spring season of July and August, among the most powerful men below the Mason-Dixon Line. It was said that “from Baltimore down to New Orleans, from St. Louis to St. Augustine there was not another man so courted and so vilified, so autocratic and insolent, so talked about and written about, so burdened and so chivvied and withal so little appreciated as Major Anderson.” A guest wrote: “You behold him upon whose breath the fate of hundreds, nay, it has been said thousands depends, the Minister Plenipotentiary and Envoy Extraordinary of the Calwells. To him Senators bow, legislators, judges, professors are supplicants, flattered beaux and flattering belles sue for his high permission, without which all is lost.” It became common to speak of him as the “Metternich of the Mountains.”

These are newer additions to Warm Springs, a favorite Jefferson getaway and still a functioning spa.

-Dave Doody

Even with Anderson’s high-handed behavior, White Sulphur remained the prime spa for those in search of pleasure. The springs became resorts more for the wealthy to meet and socialize than for those seeking their healing powers. A guest wrote in 1856 that “there is more fun frolick life & annimation at this place than all the rest of the springs put together.”

The Virginia Springs were in their heyday from the 1830s to the 1850s, when thousands of people visited the spas annually. White Sulphur Springs alone often saw more than sixteen hundred guests a day. Virginia springs proved the equal of Europe’s and sometimes superior. They were cleaner, their surroundings airier and more natural, and, in consequence, their benefits more lasting. The mountain milieu was as important as the mineral waters in ministering to body and soul.

Harold Gill, the journal’s consulting editor, contributed to the winter 2001–2002 magazine “Colonial Americans in the Swim.”