Page content

Online Extras

Extra Images

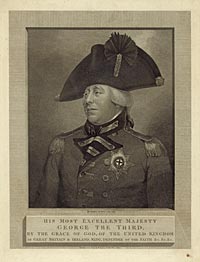

The Poisoning of King George III

Did His Medicine Drive His Majesty Mad?

by Ed Crews

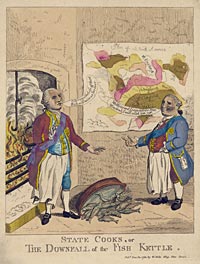

A sick king–made sicker by doses of emetic tartar–his wife, and doctor. Edward D. Way as King George III, Carrie MacDougall as Queen Charlotte, and Robert Goodman as Doctor John Willis.

There are those who think George III was nuts to drive thirteen of his American colonies out of his empire. Could it be that he was crazy? Clinically mad? Several times in his later life, the king appeared to be out of his mind, hallucinating, disoriented, chasing ladies of the court and assaulting family, physicians, and royal staff. He babbled endlessly. A physician wrote during the king’s twilight years: “His conversation in extravagance is like the detail of a dream.” His condition during these episodes—notably in 1788, 1801, 1804, and 1810—baffled and disturbed people who loved him.

In moments of lucidity, the king realized he was ill and feared the worst. In 1788, weeping and lamenting his state, he rested his head on his son’s shoulder and said, “I wish to God that I may die, for I am going to be mad.”

Since his death in 1820, historians have wondered exactly what was wrong with Britain’s monarch. Interest in the question has waxed and waned, but never really disappeared. In the 1990s, the subject revived with the release of the popular but not wholly accurate movie The Madness of King George.

Scientists, physicians, and playwrights have pondered his case, too. Some experts said he suffered from a long-term psychosis. Others saw lead poisoning as the cause. Nobody knew for sure. The patient was dead, and there was no way to examine him. All there were to study were yellowing doctor’s notes that seemed to hide as much as they revealed.

About all observers agreed on was their disapproval of eighteenth-century treatments, which were cruel and useless, and compassion for his state, especially near the end of his life.

Earlier this decade, however, science found something new. A research team working in archives and with a few strands of the king’s hair identified a likely explanation. Analysis supported the theory that George’s sufferings derived not from mental illness but from a rare hereditary metabolic condition, made worse by his medicines.

The king experienced the best-documented attack when he was fifty. By then, he had ruled for twenty-eight years, presiding over a tumultuous era in British history. Early in his reign, England won the Seven Years’ War and became the world’s greatest colonial power. A few years later, she alienated her North American colonies. That led to war, British defeat, and American independence.

Yet it did not deter British exploration and colonization elsewhere. Captain James Cook, for instance, made his first Pacific voyage, and the first convict fleet sailed to Australia. The Industrial Revolution began with James Watt awarded a patent for the steam engine. The first English cotton mill opened.

During George’s rule, English strength and pride grew, and his subjects reasonably could believe he would enjoy a long and successful reign. That expectation changed in 1788.

The early signs of disease that would lead people to believe the king mad came on in June. At the time, George reportedly suffered a severe bilious attack. His condition worsened in the weeks ahead. By October, he was seriously ill. Before long, it was doubtful he could remain on the throne.

The king went from simple discomfort to intense distress. His decline began with stomach pain, cramps, and rashes. Initially, doctors attributed the symptoms to gout or wearing wet socks or eating peas, but the patient grew worse. His stomachaches became debilitating and left him doubled over. His feet swelled. His eyes turned yellow, and his urine was brown. Mental decline ensued.

From the malady’s onset, the king appeared deranged. Increasingly erratic, he could not concentrate on affairs of state and easily became upset. One observer recorded that “the look of his eyes, the tone of his voice, every gesture and his whole deportment represented a person in a most furious passion of anger.” During one meal, he grew so agitated he lost control, grabbed his son the Prince of Wales, and threw him against a wall.

George also had trouble sleeping, and his vision blurred. He talked a lot, but his conversation was disjointed; he could not stay on topic. “He often spoke till he was exhausted, and, the moment he could recover his breath, began again, while the foam ran out of his mouth,” a member of the court wrote. He lost weight. Once, he made a “new noise in imitation of the howling of a dog.” By December, he was begging the royal staff to end his life.

Eighteenth-century medicine lacked an effective treatment for the king. Doctors did not have the insight, science, or means to heal him. They knew little about mental illness and less about the nervous system or how injury or infection could affect it. They turned to the nostrums of their age—bleeding, blistering, purging, and sedating. They kept him in an unheated room during winter. Nothing worked.

In December, a despondent royal family sought the help of Dr. John Willis, who ran an asylum and had practical experience with mental illness. Willis started professional life as a clergyman but turned to medicine. From the moment they met, the king did not like Willis any better than the other doctors on the case. George accused him of leaving a fine profession for one the king detested. “Sir, our Savior himself went about healing the sick,” Willis said. “Yes, yes. But He had not £700 for it annually,” George said.

Willis believed in humane treatment of the mentally ill, but he mixed gentleness with firmness. If the king was difficult, Willis put him in a straitjacket or had him tied to a chair and gagged. If he was cooperative, Willis gave him as much liberty as seemed practical.

George began to recover in February 1789, though it is unclear why. Given the state of medicine, it is unlikely the doctors had much to do with it. By March, his treatments were discontinued, and the patient improved.

The monarch’s illness caused what is known as the Regency Crisis when opportunists attempted to strip George of power and have his wastrel son, the Prince of Wales, serve as regent in his stead. Anti- and pro-prince forces battled mightily over the issue, but the maneuvering came to naught with the king’s recovery.

Now, George III grew more popular. Before his illness, Englishmen were not particularly attracted to him. Afterward, they warmed to him. Their affection was demonstrated in the many thanksgiving services for his recovery, the largest at St. Paul’s in April 1789.

For more than a decade, George went without further episodes, but his illness returned. He recovered from two bouts, although one in 1804 weakened him severely. A final attack in 1810 wrecked the king’s health and mental balance. His son became regent, and George descended into a decade-long private hell.

At times, he was calm, at others distraught. Often conducting conversations with people long dead, he talked constantly. He described to his dead daughter Amelia her funeral. During one of his delusions, he believed himself dead and conversed with angels. He grew his beard long and lost first his sight and then his hearing.

George died after years of suffering and isolation. Despite their grief, family and friends believed that the king finally was released from his misery. “The change,” said Princess Elizabeth, his daughter, “is a blessed one.”

Although he was out of the public eye for a decade, George was missed. The nation mourned, his funeral attracted 30,000, and the sense of loss was heartfelt.

Although people wanted to know what happened to George, a definitive answer was impossible and speculation was widespread. Beginning in the nineteenth century, many believed that the king had simply lost his mind. That position drew strength in the first half of the twentieth century from the rise of psychiatry and efforts to understand, treat, and cure mental illness.

Dr. Manfred S. Guttmacher, an American psychiatrist, took this position in his 1941 book, America’s Last King: An Interpretation of the Madness of King George III. Guttmacher believed the king’s behavior reflected a manic-depressive psychosis that lasted throughout his life.

In 1969, British psychiatrists Ida Macalpine and Richard Hunter suggested that the king suffered not from insanity but from porphyria, a rare and incurable hereditary metabolic condition not identified until the twentieth century.

Macalpine and Hunter, who were mother and son, reviewed the files on George’s illness and concluded the king had a textbook case of the disease. It is easy to see why they reached that conclusion when one reads modern descriptions of it.

porphyrias are disorders in which heme, which is in red blood cells and all tissues, does not develop correctly. Enzymes convert chemicals known as porphyrins into heme, and if the body does not properly handle those, they collect. In acute cases, this produces severe symptoms, including abdominal pain, constipation, and muscle pain. The patient’s urine can turn a deep, dark red, and sufferers often experience confusion, hallucinations, disorientation, and paranoia. Even today, porphyria victims are misdiagnosed as having a mental illness.

Research shows that almost 90 percent of those who have a gene that leads to porphyria never experience the disease. Doctors also know that such things as alcohol use, smoking, fasting, stress, and overexposure to sun can trigger it. It also is clear that the condition tends to affect women more often than men.

Though Macalpine and Hunter made a persuasive case, they did not have definitive laboratory evidence, and not everybody accepted their findings.

In 2005, The Lancet, the British medical journal, published a report supporting the porphyria theory. A research team produced evidence that showed the condition existed among George III’s descendents, suggesting a genetic link for the disorder. In addition, scientists found and tested some of the monarch’s hair clipped from his head when he died.

Attempts to extract DNA failed, but tests showed elevated levels of lead and, more significant, extraordinarily high levels of arsenic. The investigators realized quickly that this was significant—arsenic is a trigger for porphyria. Also important, the analysis showed that George probably accumulated the poison over an extended period.

“It is a very convincing explanation of the king’s attacks and could account for why he had them at such a late stage in life and why they were so severe,” Martin Warren, one of the team’s scientific detectives, told the British Broadcasting Company.

Initially, nobody knew where the arsenic originated. Study in the archives produced the answer. King George got liberal doses of emetic tartar that contained arsenic. The medicine he was given for his illness made the condition much worse. As the researchers reported in The Lancet, the original physicians’ notes “make for disturbing reading,” especially when one reads of the amount and frequency of the emetic tartar doses, the king’s violent reactions, and the deception or force often used to make him take the mixture.

The test results seem to have gained quiet acceptance. Although the case may never be decided definitively, sophisticated lab work now has offered a compelling explanation of a long-running and curious medical mystery.

George’s case still arouses sympathy. In the mid-1800s, English novelist William Makepeace Thackeray expressed well a sense of lingering sorrow still attached to the king’s final decade:

All the world knows the story of his malady: all history presents no sadder figure than that of the old man, blind and deprived of reason, wandering through the rooms of his palace, addressing imaginary parliaments, reviewing fancied troops, holding ghostly courts.

Extra Images

Ed Crews contributed to the autumn 2008 journal a story about colonial gambling.