Online Extras

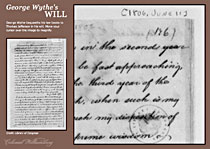

Zoomable George Wythe Will

Extra Images

Bust of George Wythe in Richmond’s old House of Delegates chamber. To Jefferson, he was “one of the greatest men of the age.”

William and Mary's Wren Building, where Wythe was student and teacher. First professor of law in the country, he was mentor to Jefferson, signer of the Declaration of Independence, and delegate to the Constitutional Convention.

A drawing of the second Williamsburg Capitol, where Wythe was clerk, burgess, and attorney general and where he conducted mock trials for students in the old General Court.

Library of Congress

A chief justice of the United States Supreme Court, John Marshall was just one of Wythe’s Virginia law students.

Library of Congress

Henry Clay, another of Wythe’s students, became John Quincy Adams’s secretary of state and later a United States senator.

“His Integrity Inflexible, and His Justice Exact”

George Wythe Teaches America

the Law

by Jack Lynch

Shakespeare’s quip—“The first thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers”—shows that distaste for the legal profession is centuries old. Early English Americans had little use for lawyers. The bard’s contemporary, Captain John Smith, nearly went to the gibbet at the hands of some of Jamestown’s pettifogging legal lights, but, Smith said, “he quickly tooke such order with such Lawyers, that he layd them by the heeles till he sent some of them prisoners for England.” Smith said Virginia had no “vse of Parliaments, Plaies, Petitions, Admiralls, Recorders, Interpreters, Chronologers, Courts of Plea, nor Iustices of peace,” and he had shipped off two “that had ingrossed all those titles, to seeke some better place of imployment.”

Lawyers might be of use in the corrupt Old World. But in a virtuous New World community, where concern for the greater good directed society’s actions, what was the need of courtrooms to settle disputes?

The utopian vision of a lawyerless world wouldn’t last long. It couldn’t. At the outset, Americans had discovered that conflicts arise in any society, however pure the intentions of its citizens, and some of those conflicts can be resolved only by recourse to the law. In any sufficiently large civilization, the laws will grow too copious and complicated for anyone without special training to master. In a society that grew to stretch nearly a thousand miles along the east coast of North America and was involved in settlements and international trade, experts in the law were essential.

How, though, were they to get the education they needed?

English legal education offered poor models for colonial imitation. The two medieval universities, Oxford and Cambridge, taught ecclesiastical law early in their histories, and Henry VIII established a Regius Professorship of Civil Law at each school. The Regius professors were learned scholars, but were handicapped: the laws they taught did not apply in England. Most English courts followed not the civil law, derived from ancient Roman law, but the common law, a body of precedents founded on no set of statutes but on earlier court decisions. Only in 1758 did Oxford begin offering a course in English law, with William Blackstone providing the Vinerian Lectures on the subject, and even then the universities had no interest in preparing lawyers to practice.

English lawyers prepared for the bar by studying at the Inns of Court in London. These fifteenth-century institutions were founded as law student dormitories, and at their best offered lectures and the opportunity to participate in mock trials and other exercises. By the eighteenth century, their serious teaching functions had lapsed, and they were little more than social clubs in which students passed a few years and emerged with the right credentials. Still, English lawyers had to go through the rite of passage if they hoped to be admitted to the profession.

This was all very well for England, but there were no Inns of Court in America. A would-be lawyer in the colonies had three ways to get his training. One was to travel to the mother country, where, as legal historian Charles E. Consalus says, “about 60 colonists attended the Inns of Court before 1760, and about 115 more went between 1760 and 1776.”

If a lengthy and expensive sojourn in London was out of the question, a simpler possibility was self-education: a student could hope to pass the bar without the benefit of a single lecture. Patrick Henry, twenty-four, took this approach, secluding himself with the Virginia statutes and the classic legal text Coke upon Littleton, emerging six weeks later to be examined in Williamsburg by lawyers Robert Carter Nicholas, Edmund Pendleton, John and Peyton Randolph, and George Wythe. Wythe declined to approve him, but Henry was narrowly admitted to the Virginia bar in September 1760.

Not everyone had Henry’s intelligence or dedication; self-education suited only the most motivated autodidacts. Besides, even those who had the discipline might not have access to the books required. Then, the most common solution was to apprentice with an established lawyer, someone who had a library and practical experience. The system was far from perfect; most lawyers were happier giving their apprentices busywork than an education. Thomas Jefferson wrote to his friend Thomas Turpin in 1769: “I always was of opinion that the placing a youth to study with an attorney was rather a prejudice than a help.”

Things began to change after independence, and it was Jefferson who set the changes in motion. In 1779, when he was governor of Virginia, he had some authority over the College of William and Mary. His autobiography describes his projects at the school:

I effected, during my residence in Williamsburg that year, a change in the organization of that institution by abolishing the Grammar school, and the two professorships of Divinity & Oriental languages, and substituting a professorship of Law & Police, one of Anatomy Medicine and Chemistry, and one of Modern languages; and the charter confining us to six professorships, we added the law of Nature & Nations, & the Fine Arts to the duties of the Moral professor, and Natural history to those of the professor of Mathematics and Natural philosophy.

There was nothing unusual about professors of medicine, languages, and mathematics. But the “professorship of Law & Police”—police here in its eighteenth-century meaning, “the regulation and control of a community; the maintenance of law and order, provision of public amenities, etc.”—was an innovation. At the time of independence there were nine colleges in the colonies, in order of their founding: Harvard; William and Mary; Yale; the College of Philadelphia, later the University of Pennsylvania; the College of New Jersey, now Princeton; King’s College, now Columbia; the College of Rhode Island, now Brown; Queen’s College, now Rutgers; and Dartmouth. None had a professor of law. Under Jefferson’s guidance, William and Mary changed that.

Jefferson’s choice for the new post was George Wythe, whose two-story brick home still stands on the western side of Williamsburg’s Palace Green, just north of Bruton Church. Born in 1726, Wythe—pronounced with—was a former William and Mary student, had read the law with his uncle Stephen Dewey, and been a Williamsburg resident since 1748, when a committee of the House of Burgesses appointed him its clerk. He had begun practicing law in the county courts in 1746, and the General Court, which sat at the Capitol. In 1753 he had been named attorney general, the third most powerful post in the colony. The following year he was elected to the House of Burgesses, representing Williamsburg, returning in 1758 for the college and in 1761 for Elizabeth City County.

Jefferson met him about 1760. It was William Small, William and Mary’s professor of natural philosophy, who introduced the sixteen-year-old student to the legal luminary, and the three men—Small, Wythe, and Jefferson—often passed evenings with Governor Francis Fauquier, where they would spend hours in talk, “& to the habitual conversations on these occasions,” Jefferson recalled, “I owed much instruction. Mr. Wythe continued to be my faithful and beloved Mentor in youth, and my most affectionate friend through life.” From 1762 to 1767, Wythe tutored him in the law. Jefferson would call him a second father.

Wythe became Williamsburg’s mayor, clerk of the House, and a member of the William and Mary board of visitors in 1768. In August 1775 he was elected a delegate to the Second Continental Congress. Fascinated by constitutional questions, he had by this time come to think America should separate from Britain; John Adams numbered him among the “independence men.” Eleven months after his appointment to the Continental Congress, he put his name to the Declaration of Independence—though whether he signed it himself or authorized a clerk to sign for him is unclear. In 1777, he became speaker of Virginia’s General Assembly, and in 1787 a delegate to the federal Constitutional Convention.

Naturally, Jefferson thought highly of his former tutor. After Wythe’s death—he was poisoned by embezzling grandnephew George Wythe Sweeney in Richmond in 1806—Jefferson wrote:

No man ever left behind him a character more venerated than George Wythe. His virtue was of the purest tint; his integrity inflexible, and his justice exact; of warm patriotism, and, devoted as he was to liberty, and the natural and equal rights of man, he might truly be called the Cato of his country, without the avarice of the Roman; for a more disinterested person never lived. Temperance and regularity in all his habits, gave him general good health, and his unaffected modesty and suavity of manners, endeared him to every one.

From the beginning of their acquaintance, Jefferson was impressed with not only his character but his intellect. That’s what prompted him to recommend Wythe for the post of professor of law and police at William and Mary.

The appointment came in December 1779, and on January 17 Wythe took up his position. By all accounts, Wythe was a first-rate teacher. As legal historian Charles R. McManis writes:

Instruction was given not only by lectures, but also by moot courts . . . and by mock legislative sessions in which committees drew up bills and debating them, with Wythe presiding as Speaker of the House and teaching parliamentary procedure in a simulated real-life atmosphere.

The Virginia government had moved to Richmond in 1780, and Wythe conducted these exercises in the old Capitol. In the classroom he had his students read legal treatises and summarize them in their commonplace books. He trained his students not only in Virginia law but in English common law, legal philosophy, and what we now call political science.

In 1789, when Ralph Izard planned to send his son to William and Mary, Jefferson told him, “I can not but approve your idea of sending your eldest son, destined for the Law, to Williamsburg.” Jefferson had kind words for the professors of mathematics, natural philosophy, and languages, but, he wrote:

The pride of the Institution is Mr. Wythe, one of the Chancellors of the State, and Professor of Law in the College. He is one of the greatest men of the age . . . gives lectures regularly, and holds Moot Courts and Parliaments, wherein he presides, and the young men debate regularly in Law and Legislation, learn the rules of Parliamentary Proceeding and acquire the habit of public speaking. . . . I know no place in the world, while the present professors remain, where I would so soon place a son.

Apart from Jefferson, his pupils included James Monroe, later to be the fifth president of the United States; Edmund Randolph, the first United States Attorney General and the second Secretary of State; federal Judge St. George Tucker, who annotated Sir William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Law of England for use in the United States; Henry Clay, the ninth Secretary of State; and John Marshall, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court from 1801 to 1835, and among the greatest jurists in American history.

Wythe was an energetic administrator. As conceived, Wythe’s course would be part of a young man’s general education—an undergraduate should know about the law, Jefferson and the others believed, but there was no way he could specialize in the subject. Under Wythe’s leadership, though, William and Mary became the first college to establish a separate program in legal education.

In a dispute with the college’s administrators, Wythe resigned in late in 1789, but went on teaching students at his home. Jefferson, who had just returned from his ambassadorship to France, wrote to his secretary William Short that “it is over with” William and Mary unless Wythe could be induced to return to the faculty. Four years later, Jefferson began to think of creating a university to replace the college. In 1791, Wythe moved to Richmond to assume new duties as judge on the state’s High Court of Chancery.

Former student St. George Tucker took the William and Mary chair in 1790—he, too, would quit in a fight with the administration—but the program Wythe put in place continued, and beginning in 1793, the college offered a new degree, bachelor of law. The first recipient was William H. Cabell, who would become Virginia’s governor.

Nevertheless, the William and Mary model did not catch on. The Litchfield School in Connecticut, which had been training lawyers since 1773, had grown out of the apprenticeship system; it taught law as a trade, without connection to a liberal arts college. And Harvard, which in 1816 became the second college to offer education in law, followed Litchfield in treating legal studies as a trade. Law would eventually become a graduate program, separate from the undergraduate college, and the bachelor of laws degree gave way to a doctor of laws degree.

As more law schools were founded in the early nineteenth century, they followed Harvard. William and Mary eventually adopted the postgraduate model; the Civil War forced the law school to close, and, when it reopened in the twentieth century, it followed Harvard’s pattern.

Wythe’s influence long outlived him. His bachelor of law program didn’t last, but he established the study of law as an academic subject. And his roster of distinguished students, many of whom went on to shape not just the study of law but the laws themselves, shows that Wythe’s legacy remains relevant today. In his devotion to the law, to its underlying philosophy, and especially to his students, Jefferson’s “second father” made himself the father of American jurisprudence.

Extra Images

The George Wythe house stands as a handsome monument in all seasons to its namesake's celebrated noble character.

Jack Lynch, author of Becoming Shakespeare: The Unlikely Afterlife That Turned a Provincial Playwright into the Bard (Walker & Co., 2007) is associate professor of English at Rutgers University. He contributed to the autumn 2009 journal “‘The Greatest Practical Approach to Exactness’: The Problem of Apportionment and Washington’s First Veto.”

Suggestions for further reading:

- Charles E. Consalus, “Legal Education during the Colonial Period, 1663–1776,” Journal of Legal Education 29, no. 3 (1978): 295–310.

- Robert M. Hughes, “William and Mary: The First American Law School,” William and Mary Quarterly, 2d series, vol. 2, no. 1 (Jan. 1922): 40–48.

- Charles R. McManis, “The History of First Century American Legal Education: A Revisionist Perspective,” Washington University Law Quarterly 59 (1981): 597–659.

- Alfred Zantzinger Reed, Training for the Public Profession of the Law: Historical Development and Principal Contemporary Problems of Legal Education in the United States with Some Account of Conditions in England and Canada (New York, 1921).

- Steve Sheppard, ed., The History of Legal Education in the United States: Commentaries and Primary Sources, 2 vols. (Pasadena, CA, 1999).