Page content

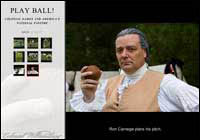

Play Ball!

Colonial Games and America's National Pastime

by Ed Crews

Photos by Dave Doody

Trap-ball, and such variants as stool-ball and base-ball, are common ancestors of our baseball. In a game of trap-ball, Wilhemina Grow strikes the lever in the trap, which flips the ball in the air. She then swings away, hoping no one makes a catch for an out.

At St. Mary's City in Maryland, interpreters re-create the bat-and-ball games Polish workers are reported to have played at Jamestown in 1609.

Baseball's origins skip a long and crooked base path back to the Middle Ages, passing through a cricket match in the colonies, played, from left, by Peter Stinely, Frank Megargee, Mike Luzzi, Bill Rose, Cash Arehart, Rick Gilliland; watched by Dennis Watson.

Games with balls and bats were favored recreations among soldiers during the Revolution. General Washington, here Ron Carnegie, played catch with his officers, from left, Dale Smoot, Justin Chapman, Tom DeRose, and Stewart Pittman.

Abner Doubleday, left, was a Civil War general but not, despite popular belief, the father of baseball.

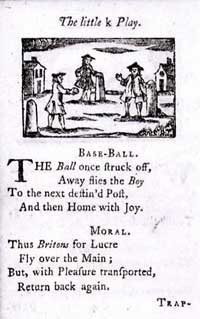

A Pretty Little Pocket-Book, intended for the Amusement of Little Master Tommy, and Pretty Miss Polly. . . . J. Newbery, 1760. Early Printed Collections, The British Library, Library of Congress exhibition - John Bull & Uncle Sam: Four Centuries of British-American Relations.

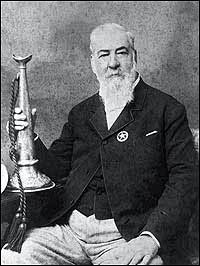

Laying better claim to the title of Father of Baseball is Alexander Cartwright, whose innovations include nine men and nine innings, three outs, and a diamond-shaped playing field.

The search for the beginnings of baseball has followed some false leads, wandered down a few crooked byways, and led occasionally to surprise. The next turn in the road could carry the game's historians to playing fields in seventeenth-century Virginia. According to baseball historian Frank Ceresi, there we may discover that the game's earliest American roots took hold in the soil of early Jamestown or maybe elsewhere in the Old Dominion's Tidewater.

Ceresi is author of Baseball in Washington, a look at the game in the nation's capital. He is writing a book on baseball treasures in the Library of Congress and consults with museums and Sotheby's auction house about sports memorabilia. "I think all the seeds of the game have not been discovered," he said. "In the records of the Northern Neck and Jamestown you're going to find things. This will be the next wave in the study of this topic."

Ceresi's theory is novel, but logical. It reflects scholarship that traces baseball to folk games settlers brought from the British Isles. Because the British came early to Virginia, it requires but a small leap of imagination to reach the possibility that the Mother of Presidents also may be the birthplace of the national pastime. Polish workers, some of whom were glassblowers, reportedly played a bat-and-ball game at Jamestown in 1609. Native Americans reportedly watched. But that contest, though it illustrates that people of the 1600s loved and played bat-and-ball games, is not regarded as the roots of baseball.

We know, too, that the inhabitants of early Virginia and other English colonies, like Plymouth, loved folk games that required bats, balls, and base running. They played enthusiastically, sometimes in the face of official disapproval. But children hit balls and caught them just as Little Leaguers do today. Revolutionary War soldiers filled time between battles with stick-and-ball recreation. Plantation owners competed at cricket, apparently a cousin—not a forerunner—of baseball. General George Washington relaxed by playing catch with his staff.

The long-standing interest in baseball's past has a lot to do with its cultural roots," Ceresi said. "Baseball is part of American history and culture, and that feeds into the interest folks have with the intricacies of the game and the people who played it."

Baseball fans care about the genealogy of what Walt Whitman called "our game." But interest sometimes leads to fabrication. Witness the wrongheaded and resilient Doubleday Myth.

In 1908, sporting goods mogul Albert Spalding announced that Union Civil War General Abner Doubleday invented baseball in 1839 at Cooperstown, New York. Spalding's claim derived from flimsy evidence. His story also smacked of economic self-interest, as well as pointed to the country's robust nationalism and distrust of immigrants and foreign ideas at the time. Historians today are not sure that Doubleday ever saw a baseball or a baseball game.

Nevertheless, the Doubleday Myth thrived for decades, promoted on stamps and bubblegum cards and in textbooks, movies, sportscasts, newspapers, and magazines. The National Baseball Hall of Fame today is in Cooperstown largely because of Spalding, but the Doubleday story began to crumble in the late 1940s. As it did, some people credited Native Americans with creating the game. Others argued for the Dutch. Still others saw English roots in the game of rounders—a game, like cricket, that seems to be a cousin or brother to baseball and not a parent.

Another group of researchers focuses exclusively on nineteenth-century events. Among these people, the title Inventor of Baseball goes to Alexander Cartwright. In the 1840s, he gave the game its diamond-shaped playing field, nine-man teams, three-out innings, and nine-inning games. He also helped found the first modern baseball team—the Knickerbocker Nine.

Since the 1960s, researchers have looked past the nineteenth century and into the eighteenth and seventeenth centuries for the game's earliest forms.

Today, sport is a serious, well-organized big business. As historian Allen Guttmann noted in his book A Whole New Ball Game: An Interpretation of American Sport, uniform rules, data collection, rigorous training, and bureaucracy distinguish modern athletic competition.

In America and Europe during the 1600s or 1700s, recreation was unstructured, ad hoc, and sometimes violent. Rules varied by tradition, region, and local circumstances. Rough-and-tumble competition was widespread, and common people loved it. Authority here and abroad tended to tolerate—if not condemn—it.

The first colonists at Jamestown and Plymouth had little time for pleasure. Life was hard and survival demanded almost all their strength, focus, and time. But the settlers did play games, and as life slowly became easier, free time increased. People played more. For the Pilgrims, the country's original killjoys, that was a problem. Having a good time often seemed to them like a bad idea. That explains why an irate Governor William Bradford broke up a baseball-like game in Plymouth among workmen on Christmas Day 1621. A contemporary report said: "he found them in the streete at play, openly; some pitching the barr & some at stoole-ball, and shuch like sports. So he went to them, and took away their implements. . . ."

Pilgrim hard-heartedness melted a little when it came to children, though. "New England parents also allowed their children to play with dolls and toys," historian Benjamin G. Ruder wrote in American Sports: From the Age of Folk Games to the Age of Spectators. "When young boys had the leisure time and were orderly, authorities usually permitted them to play informal football, bat and ball, and stool-ball matches. Nonetheless, the conscientious Puritan always worried that recreation would become an end in itself."

John Adams persisted in the Puritan ethic. "I was not sent to this world to spend my days in sport, diversion and pleasure," he wrote. "I was born for business; for both activity and study."

If he eschewed ball games, others embraced them. William Byrd, a Virginia plantation owner, loved cricket. He played often with James River neighbors. "About 10 o'clock," one of his diary entries reads, "Major Harrison, Hal Harrison, James Burwell and Mr. Doyly came to play at cricket. Isham Randolph, Mr. Doyly and I played with them three for a crown. We won one game, they won two."

Cricket was mainly an upper-crust pastime in the 1700s. People from other social classes enjoyed trap-ball, stool-ball, and base-ball.

Children particularly loved trap-ball. Trap-ball's appeal is its simplicity. Any number of people can play the game. It requires a bat, ball, and "trap," a wooden box with a seesaw. The batter puts the ball over the seesaw and steps on it. As the ball rises, he hits it. Fielders try to become batters by catching a fly or retrieving a grounder and hitting the trap with the ball.

Ball games also were popular with Continental soldiers. Records tell of troops walking miles to find a level playing field. Diaries mention spirited games resulting in cut lips, dislocated jaws, and brawls. "The day was so bad and so much labor going on, that we had no exercise, but some ball play—at which some dispute arose among the officers, but was quelled without rising high," a soldier wrote in September 1776.

The ball and bat-and-ball games of colonial America had several versions. Take stool-ball. It was played widely across the British Isles for years. Colonial Williamsburg's Junior Interpreters today play a simple form. Players form a circle around a stool. They try to hit the stool with a ball. A player who bats the ball away with his hand defends the stool. Players in the circle may pass the ball to others in the circle or throw it at the stool. Whoever hits the stool becomes its defender.

Stool-ball also had a more complicated form. This involved several stools with several defenders. A pitcher tried to hit a stool. Using his hand, a defender batted away the ball. When that happened, the defenders ran around the stools. The pitcher retrieved the ball and tried to hit a runner between stools. If he succeeded, he became a defender. The ball-struck defender became the pitcher. Some variations of the game equipped the defender with a bat.

A soft-spoken California fan and self-styled amateur historian, David Block spent years examining baseball's genesis. He looked at thousands of books, images, and documents, some dating to the medieval period. He questioned every popular assumption about the game and accepted nothing he could not prove. The result is Baseball Before We Knew It: A Search for the Roots of the Game, a book published in 2005 by the University of Nebraska Press. Fans, critics, historians, sportswriters, and publications from the New York Times and Sports Illustrated have praised it. For Block, links between folk games and the national pastime are logical and documented, but not as firm as he might like. "We can only surmise the links to modern baseball," he said during an interview. "I'm merely hazarding an estimation on the characteristics that are similar between baseball and early games."

Block thinks stool-ball, trap-ball, and base-ball, played in the 1700s, are particularly noteworthy in the early evolutionary stages of baseball. Stool-ball involved pitching, running bases, and defending bases. Trap-ball had batting. Ultimately, base-ball had these traits and more. "Base-ball is baseball at its crudest, most primitive stage," Block said.

The first printed reference to base-ball appeared in an English children's book, A Little Pretty Pocket-Book, in 1744:

The ball once struck off,

Away flies the boy.

To the next destined post,

And then home with joy.

An accompanying illustration shows boys using posts for bases and a pitcher with a ball. At that point, the game has no bat. But it got one before century's end, according to a German reference book published in 1796 and written by Johann Christoph Friedrich Gutsmiths that describes "das englische Base-ball."

That game naturally had some differences with today's version. A good example is the practice of putting a base runner out by "soaking"—hitting—him with the ball. Another dissimilarity is the possible presence of more than four bases.

Far more striking are the similarities between base-ball and baseball. A batter got three chances to hit a ball. If he succeeded, he ran bases counterclockwise past as many as he safely could, aiming to reach home. Only one runner could occupy a base. To get a runner out, the defending team could catch a fly, touch a runner, or throw to a base. To Block, the connection between this game and the national pastime is significant.

"The characteristics introduced in A Little Pretty Pocket-Book, and elaborated by the Gutsmiths work, have attained full maturity in our modern game," Block wrote. "No other pastime more directly contributed to the development of American baseball than its diminutive eighteenth-century English namesake."

Block said American base-ball stopped borrowing elements from other folk games, although refinements continued through the 1840s with Cartwright's contributions.

Fans may enjoy knowing baseball's origins, but does it otherwise matter? Kids will still join Little League. Players will play. Fans will cheer. Block still will root for the Oakland As and Ceresi the Washington Nationals. Nevertheless, Block believes that knowing the facts has value in and of itself. The quest should continue if only to set the record straight.

Ceresi believes that finding baseball's origins is more than a matter of verification. He says that the game is a microcosm of American life that tells us much about the country's larger history whether the topic is sports, civil rights, labor relations, or immigration and assimilation.

"People need to know their heritage," he said. "When people get into genealogy, the deeper they go, the more their interest grows. It's the same way with the national pastime."

Ceresi is right about how deeper knowledge can lead to greater interest. Every year, hundreds of guests join Colonial Williamsburg's junior interpreters in trap-ball games on Palace Green.

"Guests—groups and individuals—can and do play with us," said Jordan Bristow, a young volunteer who interprets the life of colonial children. "They love the game. Sometimes they'll play it for a long, long time."

Several years ago, the junior interpreters demonstrated trap-ball at a Norfolk minor league baseball game. The home team got involved. Then, the visiting team wanted a few at bats. Eventually, the umpires had to break up the trap-ball competition so the real baseball game could start.

Ed Crews, is a longtime baseball fan. He still believes that the Dodgers belong in Brooklyn and cheers for the Atlanta Braves, the New York Yankees, and anybody playing against the New York Mets. Ed contributed to the Winter 2008 journal story about Colonial Williamsburg's Canadian horses.

Suggestions for further reading: