Page content

Timberheads and Talking Stools

Puppets Pulled the Strings of Eighteenth-Century Audiences

by James Breig

When readers of the Gentleman's Magazine opened the May 1738 issue of the London-based publication, they should have been greatly amused. Inside was a "humble petition" directed "to the Worshipful Licensers of the Stage." It came from the eighteenth-century actor "Punch, master of the Artificial Company of Comedians in the Hay-market." Identifying himself as a fervent Christian and obedient citizen who never acted on Sundays, he begged the licensers not to limit his performances on other days of the week. His petition, he said, was necessitated by a letter threatening to turn his body "into Tobacco-Stoppers" if he acted on Wednesdays and Fridays during Lent. Punch, as the readers knew, was a puppet.

That a "timberhead"—a term he would apply to himself in another article—could contribute to a major magazine is a clue to how popular puppetry was in the eighteenth century. Scarlatti and Haydn composed operas for puppet theaters, and Henry Fielding and Joseph Addison penned plays and poems for them. In 1728, James Ralph, an American in London, said:

I cannot view a well-executed puppet show without extravagant emotions of pleasure: to see our artists ...animate a bit of wood and give life, speech, and motion, perhaps to what was the leg of a joint-stool, strikes me with a pleasing surprise and prepossesses me wonderfully in favor of those little wooden actors.

Writing in 1801, British author and antiquary Joseph Strutt said, "It is ...certain, that puppet-shows attracted the notice of the public at the commencement of the last century, and rivaled in some degree the more pompous exhibitions of the larger theatres." Twentieth-century puppet historian George Speaight said, "Few periods of history can have been so sympathetic to puppets as the eighteenth century. Never before or since have the puppets played quite so effective and so well publicized a part in fashionable society."

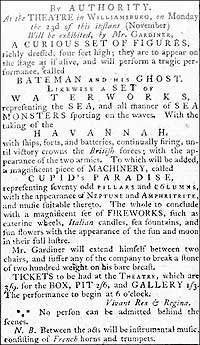

The popularity of puppets in the 1700s extended to America. Thomas Jefferson attended a puppet performance in Williamsburg while a student at the College of William and Mary. George Washington, who jotted the cost in his account book, attended a "Puppit Shew" in Williamsburg in 1776. He saw Peter Gardiner's "curious set of figures, richly dressed, four feet high," in a "tragic performance called 'Bateman and his Ghost.'" Highlights of the performance included "water works, representing the sea," a diorama, fireworks, and "instrumental music, consisting of French horns and trumpets."

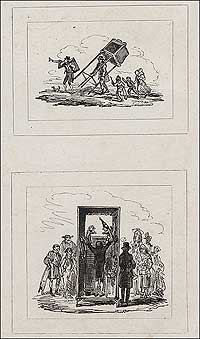

The description of the show is taken from an advertisement in the Virginia Gazette, published in Williamsburg, and demonstrates that the simple phrase "puppet show" could conceal an elaborate production. Eighteenth-century puppetry ranged from street-corner performances to theaters where entrepreneurs presented flashy productions of classical legends, Scripture stories, and parodies of contemporary society. Part of the appeal of puppets, says Joel Schechter, editor of Popular Theatre: A Source Book, is that "before the advent of mass communications, touring acting companies and puppeteers could bring their artistry to audiences in different locations, where the portable entertainment was a special event. The performers made their art accessible by going to their audience."

Carson Hudson, who directed the puppet program at Colonial Williamsburg for fifteen years and now heads Historical Diversions, a company that specializes in history education, thinks the explanation for puppets' popularity is simple: "People are fascinated by 'little things,' or miniatures of real things. You can see examples of this in model railroaders, dolls and dollhouses, toy soldiers. When you combine this with actual movement and a storyline, then you've got a combination that easily entertains people." John Bell, a professor of theater history at Emerson College, says that "the central mystery to puppets is that they are dead things which we bring to life with movement and sound. Everyone in the audience knows that the piece of leather, wood, papier-mâché, plastic, bone or Muppet fur is not a real human being or animal; and yet we all allow ourselves to imagine that the object is capable of existence." Julie Taymor, the theatrical director who created The Lion King on Broadway, says in Schechter's book that the magic of puppetry lies in being able to "really put life into inanimate objects...You know it's dead and therefore you're giving it a soul, a life."

Puppetry has a reputation as an inconsequential subdivision of show business. But that is not true now, as Broadway plays like Avenue Q and political satires testify. And it was not true in the eighteenth century. Punch's letter to the magazine proves that.

Behind its puckish premise lay a sober commentary on a serious social issue. In 1737, the Licensing Act restricted legitimate theaters in England. The crackdown targeted playwrights who were growing vitriolic toward the government, particularly Robert Walpole, the prime minister. The law required that a script be submitted to the government at least two weeks before its performance, "together with an account of the playhouse ...and the time when the same is intended to be first acted." The Lord Chamberlain could, "as often as he shall think fit, prohibit the acting" of the play. The penalty for failure to follow the law was a hefty fifty pounds—and the closing of the theater.

As a result, writes Henryk Jurkowski in A History of European Puppetry: From Its Origins to the End of the Eighteenth Century, "Puppet theatre in England became an equal partner of other forms of theatre...Writers, designers and actors . . . looked to puppetry for an alternative career, as it seemed to offer opportunities, especially to those with satirical intentions." Perhaps because the censors had little regard for puppetry, the government turned a blind eye to puppet shows. The same thing had happened a century before when Parliament shuttered the theaters; in 1643, actors issued a public complaint that while they were out of work, "puppit-plays ...are still up with uncontrolled allowance." In 1737, the opportunities offered by puppetry were seized by the likes of Fielding, who had incorporated puppets into his plays and would later include scenes about them in Tom Jones. In that novel, a character says: "I love a puppet-show of all the pastimes upon earth." The author, familiar with the potential of puppetry for satire, used that outlet after the passage of the Licensing Act, which had been occasioned in large part by his antigovernment play, Pasquin.

In this shift, Fielding might have wandered far afield. A prominent puppeteer of that period was "Madame de la Nash," about whom little is known. But one scholar recently theorized that Fielding had donned the pseudonym. If so, he wasn't the only cross-dressing puppeteer of the century. Though Fielding's transgender move was figurative, it was literal for Charlotte Charke, an actress who had appeared in Pasquin. The daughter of dramatist and poet laureate Colley Cibber, she was given to wearing men's clothing and renamed herself Charles Brown to live as a man for years. She, too, took up puppetry in the wake of the Licensing Act. The idiosyncratic corps of "motion men"—as puppeteers were sometimes called—also included a one-legged impresario named Foote. Another, Harry Roe, once conned a bailiff into not arresting him until after the show was over. At the finale, Punch announced that "the performances are obliged to be discontinued for a time ...Harry Roe's gone." The puppeteer had escaped by a backstage window.

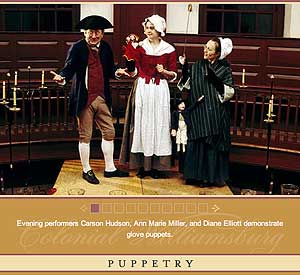

From left, Bill Rose, Dawn Lunn, Anne Marie Millar, and Carson Hudson present a Grand Medley of Entertainments in Colonial Williamsburg's Kimball Theatre.

Anthropomorphic figures of wood and other materials romp throughout recorded time and across all cultures. Rod, hand, shadow, finger, and string puppets have been used in human societies as part of religious ceremonies, theatrical presentations, and child's play. Dolls, after all, are puppets that children manipulate to enact dramas of their own creation. In the Middle Ages, puppets became more soulful when they were used in mystery and miracle plays. During the Renaissance, the wooden actors provided diversions to fair-goers. In the seventeenth century, Samuel Pepys recorded several times in his diary that he passed the hours at puppet plays, attending one twice. In 1668, he saw "an excellent play, the more I see it, the more I love the wit of it." He rated an Italian puppet show "the best that I ever saw" but panned a performance that ridiculed the Puritans.

Much of puppetry for the past century has been directed at children—Pinocchio and Howdy Doody, who are marionettes; Lamb Chop, a sock puppet; Fred Rogers' Neighborhood of Make-Believe with its traditional hand puppets; and the fuzzy Muppets of many productions which come in several forms.

One of the longest-running plays on Broadway is The Lion King, in which actors wear their puppets, like Big Bird of Sesame Street. But alongside those figures, there have been wooden heads with less-than-childish intentions and purposes. Bell pointed out that TV advertising "routinely uses puppets and not just for kids' products. Look also at political demonstrations: Puppets are constant features of these adult events and wouldn't be there if they weren't successful communicators."

Ridicule has long been a puppet prerogative. On radio, Charlie McCarthy, a ventriloquist's dummy, traded insults with W. C. Fields; on British TV in the 1980s and '90s, Spitting Images mimicked politicians through the use of sculpted figures; Conan O'Brien's late-night talk show features appearances by Triumph, the Insult Comic Dog, a rubbery puppet that chews cigars and spews scatological invective, particularly in the direction of show-business bigwigs.

Poking fun at higher-ups was common in the 1700s as well, and it was one reason puppetry appealed to the masses, according to John Mullan, co-editor of Eighteenth-Century Popular Culture: A Selection. He writes: "My hunch is that irreverence was crucial to the appeal of puppet shows, and that they frequently had some mocking relationship with polite culture." As a result, the appeal of puppet shows was thought to be to the lowest classes. In 1699, an observer said that the audience at a puppet show was "lazy, lousy-looking rascals, and so hateful a throng of beggardly, sluttish strumpets." A century later, Strutt wrote of puppet shows "without the least degree of taste or propriety...The dialogues were mere jumbles of absurdity and nonsense, intermixed with low immoral discourses passing between Punch and the fiddler."

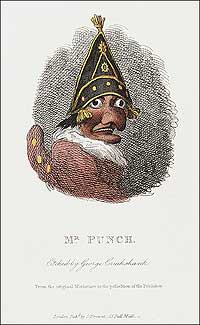

Punch was the bugs bunny of his era in renown and temperament. Schechter writes that Punch "defied law, order and decorum through his comic anarchy." Hudson says Punch's punch lines were filled with "violence, racism, sexism, and bathroom humor. The early Punch and Judy shows contained much that would offend people today."

The development of puppets in Europe in the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries is tied up in the evolution of the hunchbacked and hooked-nose figure who was born in Italy as Pulcinella, moved to France as Polichinelle, and landed in England as Punchinello, later to be shortened to Punch. He acquired a wife along the way, who was initially called Joan. In the nineteenth century, her name shifted to Judy. Punch was a knockabout comedian and wiseacre who freely wielded an ever-handy cudgel to batter his enemies, including Satan.

Punch—who was usually a string puppet in the eighteenth century, Hudson says—had his own skits, but he was employed in other settings to provide broad comic relief. He popped up even when puppet shows strove for decorum. Perhaps the most prominent practitioner of higher-class puppetry in the eighteenth century was Martin Powell, a Dubliner whose figures performed not only in taverns but also in theaters. His plays included retellings of the tales of Dick Whittington and operas based on the classical myth of Venus and Adonis, or the fall of Troy. But Powell, a smart businessman, didn't shy away from exploiting Punch's appeal. When The Creation of the World was enacted with scenes from the Bible, Punch and Joan showed up on the deck of Noah's ark to caper and quarrel.

Like many puppets of the time—and indeed into early television—Punch spoke in a high-pitched squeal that was often inarticulate. Audiences knew the story as much from the accompanying pantomime as from dialogue. The noise was achieved by the puppeteer holding a reed or leaf in his mouth and whistling through it. Madame de la Nash once announced: "As the squeaking of the puppets has been thought to be disagreeable that objection is now removed, by their speaking by natural voices."

Whether squeaking or speaking, swatting the devil or his wife, or appearing as himself or in a role, people could not get enough of Punch. Jonathan Swift mentioned Punch's voice and his fame when he rhymed in 1728:

Observe, the Audience is in Pain,Punch would sail to America, but other puppets, so to speak, gathered on the shores to greet him. Native peoples in North and South America, as in other cultures around the world, operated puppets. For instance, shamans used them in religious services. More puppets arrived with the early Europeans. In 1524, a puppet show is reported to have been performed in Mexico for Cortes's troops. There was a woman puppeteer in Peru as early as 1696. A troupe of motion men moved into Barbados in the early 1700s, while the mainland welcomed puppeteers to Philadelphia, Boston, and Williamsburg.

While Punch is hid behind the Scene,

But when they hear his rusty Voice,

With what Impatience they rejoice....

Sho'ld Faustus with the Devil behind him,

Enter the Stage they never mind him,

If Punch, to spur their fancy, shews

In at the door his monstrous Nose.

In 1742, the Pennsylvania Gazette advertised performances by moveable or "changeable Figures of two Feet high," including "a merry Dialogue between Punch and Joan his Wife." In 1769, the newspaper reported the theft of "an Apparatus of a Puppet Show, Punch Head, remarkably large." The puppets belonged to a woman named Mary Chapman.

That year, apparently for the first time, the Virginia Gazette announced that "by permission of his excellency the Governor, for the entertainment of the curious," Peter Gardiner, whose show would be seen by Washington seven years later, would present puppets in The Babes in the Woods. Tickets went on sale at the Raleigh Tavern. In 1776, Washington watched Gardiner's show. A writer in the Gazette said that "in the midst of this crash of ruin," George III "can go composedly to see a puppet show or laugh with a buffoon. O wretched England!"

But, o

lucky guests of Colonial Williamsburg when they attend A Grand Medley of

Entertainments or other eighteenth-century puppet shows re-created for the

delight of modern audiences—who seem pleased as punch to string along.

![]()

James Breig, an Albany, New York, editor and writer, contributed a story about colonial dogs to the autumn 2004 journal.

Suggestions for further reading:

- Henryk Jurkowski and Penny Francis, A History of European Puppetry: From Its Origins to the End of the Nineteenth Century (Lewiston, NY, 1998).

- Paul McPharlin, The Puppet Theatre in America: A History, 1524-1948 (Boston, 1949).

- Jane Moody, Illegitimate Theatre in London, 1770-1840 (Cambridge, 2000).

- John Mullan and Christopher Reid, eds., Eighteenth-Century Popular Culture: A Selection (Oxford, 2000).

- Joel Schechter, ed., Popular Theatre: A Sourcebook (London, 2003).

- Scott Cutler Shershow, Puppets and Popular Culture (Ithaca, NY, 1995).

- George Speaight, History of English Puppet Theatre (Carbondale, IL, 1955).