Page content

Of Sharpers, Mumpers, and Fourberies

Some Early American Impostors and Rogues

by Jack Lynch

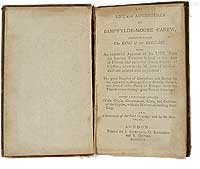

Bampfylde-Moore Carew exported himself and his crimes to the colonies, where he published his memoirs.

A new country offers new opportunities. Colonial America appealed to people because it offered them a fresh start, a chance to begin life anew. In the New World a person could establish a new identity, free from the onerous traditions and snobberies of the Old. And it pleased Americans to think of themselves as the sort of people who gave strangers the benefit of the doubt, who judged men by their characters and achievements rather than by family ties and pedigrees.

But the liberty honest folk had to reinvent themselves gave the same opportunity to the less scrupulous. Knaves and rascals learned to take advantage of this characteristically American trust: the colonies swarmed with rogues, tricksters, impostors, and con men. Their stories are often entertaining—narratives about their adventures circulated widely in their lifetimes and long afterward—but they're also informative. These cheats, or "sharpers" as they were known at the time, show how fluid identity could be in the eighteenth century.

Some of these scoundrels were imports from the mother country. Bampfylde-Moore Carew, for instance, was the wayward son of a Devonshire minister. He traveled around southwest England under such false identities as a lunatic called "Mad Tom," a sailor, a preacher, and an old woman, bilking people of their money. Caught in 1739, he was transported to Maryland, where he quickly escaped from authorities and traveled to Connecticut to resume his cheats and cons. Now a Quaker, now a shipwrecked sailor, now a sufferer from smallpox, he imposed on uncounted dupes. His inventiveness made him legendary—he was willing to take risks, even foolish ones, because it made for a better story. His association with a band of Gypsies added to his mystique hints of occult knowledge and outlandish rituals. After a crime spree across the colonies he returned to England, was captured and sent back to Maryland, escaped again, and returned once more to England.

After that it becomes difficult to disentangle fact from fiction. By some accounts he traveled with the forces of Bonnie Prince Charlie, though some historians are dubious. As often happens with larger-than-life criminals, rumors grew into legends, and speculation was passed off as fact. Several supposed confessions and memoirs, like The Life and Adventures of Mr. Bampfylde-Moore Carew, Commonly Called the King of the Beggars, told the story of the famous "mumper," in the words of the Oxford English Dictionary, "a person who sponges on others." These books went through many editions, and kept the story of Carew and his "fourberies"—deceptions, frauds, tricks, and impostures—in circulation for decades. So widespread and so lasting was his fame that as late as 1818, more than seventy years after his exploits, John Adams could write to Thomas Jefferson about Jesuits traveling the country "in as many shapes and disguises as ever a king of the gypsies, Bampfylde-Moore Carew himself, assumed."

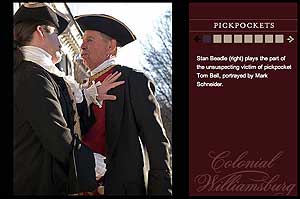

Interpreter Mark Schneider as Tom Bell makes off with Stan Beadle's watch; Latoya Redman stands by aghast.

Other early American impostors were homegrown. Stephen Burroughs, born in 1765, grew up in New Hampshire and Vermont, and tells us he spent his youth "almost perpetually prosecuting some scene of amusement." His amusements turned criminal. After two years at Dartmouth College he dropped out and began what historian Larry Cebula calls "a colorful career of thief, counterfeiter, schoolteacher, and seducer of schoolgirls." Like Carew, he was a master of the assumed identity, a trick he learned when he pretended to be someone else to avoid detection after one of his adventures.

When as a young man, Burroughs stole watermelons from a farmer, he had the audacity to join the search party that set out to find the criminal. He ran a counterfeiting operation, and smuggled phony currency from Canada into America. His wit and daring were legendary: he wrote in his popular volume of memoirs that he set fire to the prison where he was confined, resolved to escape or die. No one was killed. His mythical standing grew. "It was currently reported," Burroughs wrote, "that the devil had assisted me, in my attempts to break jail."

As Cebula says, "So great was his fame that unsolved crimes were routinely ascribed to him and other criminals sometimes gave the name 'Stephen Burroughs' when they were arrested."

The most notorious colonial impostor of all was Tom Bell. He featured in

more than a hundred newspaper articles between 1738 and 1755, making him one of

the most famous men in early America. Born in Boston in 1713, Bell was enrolled

in Boston Latin School and Harvard, and used his education to ingratiate

himself with the wealthy and powerful. During a career of fifty years,

historian Carl Bridenbaugh "pursued him in the colonial newspapers as

resolutely as Inspector Javert did Jean Valjean," and Bridenbaugh offers the

best description of this "uniquely American mountebank."

Not long after

arriving at Harvard, Bell was in trouble. In December 1732, his second year, he

was publicly admonished for stealing. A few months later he was expelled for

"other acts of theft, particularly of stealing private Letters ...and . . .

a cake of chocolate," an offense he compounded with "the most notorious,

complicated lying."

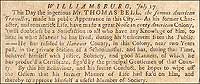

With just over £8 in hand, he faced bills of about £50. His tastes were extravagant. He owed £30 to his tailor alone. When his creditors turned to the courts to recover their money, Bell fled Boston, sailing to London, then to Jamaica. The first sign we have of his illicit adventures appears in Williamsburg in July 1738, when the Virginia Gazette ran a notice:

Tom Bell was awarded "19 Lashes at a Cart's Tail" for his crimes. Interpreter Tom Hay lays them on while, from left, Bob Shewanick, Kristin Spivey, Megan Spivey, and Jamie Spivey witness the punishment. Allison Harcourt drives the cart.

On the 2d of this instant July one Thomas Bell, alias Francis Partridge Hutchinson, who was committed to the Isle of Wight Gaol, for Felony, made his Escape...This is therefore to desire all Persons to aid and assist in taking up the said Felon, so that he may be brought to Justice.Justice caught up with him four months later in New York, when he was convicted "for falsely, unlawfully, unjustly, knowingly, fraudulently, and deceitfully, composing, writing, and inventing a false, fictitious, Counterfeit, and invented Letter . . . to Robert Levingston and Peter Levingston, ...to defraud the said Levingstons of £50 Sterling." He was sentenced to "19 Lashes at a Cart's Tail, and ...drawn through the principal Streets" of the city.

Public chastisement failed to reform him, and he continued his exploits, spawning Robin Hood-style legends as he went. Bell sometimes resorted to straightforward theft and counterfeiting, but his usual modus operandi was that of the impostor and confidence man. He impressed people with his classical learning, his genteel manners, and his fancy clothes. And he usually arrived with some tale of woe, which prompted trusting people to invite him into their homes and to offer him money or whatever else he needed. All he really needed was their trust, for he knew that was the key to all the rest. As the Pennsylvania Gazette reported in February 1743:

He has it seems made it his Business for several Years to travel from Colony to Colony, personating different People, forging Bills, Letters of Credit, &c. and frequently pretending Distress, imposed grosly on the charitable and compassionate.Many of Bell's stories are entertaining, but sometimes his behavior had grave consequences. In 1739 he fled to Speightstown, Barbados, where he passed as Gilbert Burnet, son of a late Massachusetts governor and grandson of a famous English historian, and got himself invited to high-profile social events. When he fled from a Jewish wedding carrying off the guests' money, he was captured and beaten; the spectacle of Jews beating a Christian, especially one supposedly so respectable, prompted hotheaded locals to burn down their synagogue. Bridenbaugh calls the synagogue burning "the earliest anti-Semitic riot on record in the New World."

Another time Bell nearly cost an innocent man his life. Traveling in New Jersey in 1741, he was told he looked very much like the famous Reverend John Rowland of Boston. Never one to pass up an opportunity for mischief making, he took advantage of the coincidence. Kindly New Jerseyans, delighted to meet such a prestigious clergyman, invited him into their homes, and asked him to preach on Sunday. He agreed, but, as he approached the church, he said he remembered that he had left his sermon at the house. He quickly rode home—and made off with his host family's horse, money, and papers, a capital offense. This would be bad enough, but the real Rowland was soon taken up and charged with the theft. Rowland escaped prosecution only when witnesses were able to prove he had been preaching in Pennsylvania on the day of the robberies.

What can we learn from these tales of deception and imposture? They show us that personal identity was fluid in the colonies. The self-made man is a mainstay of our early history: the archetypal American hero is born not in a palace but in a log cabin, and makes his way in the world by the force of his personality. But while we often dwell on the advantages that come from self-creation, we should remember that imposters thrive in a republic in which a person's identity is what he or she makes it.

Some of the cheats used that distinctively American idiom to justify their careers: Stephen Burroughs, for example, wrote in his Memoirs, "I consider a man's merit to rest entirely with himself, without any regard to family, blood, or connection." Stirring words—until we realize what he made of this admirably democratic sentiment, for the charlatan is the other side of the republican coin.

This may be why the con man is central in so many works of American literature. The public has adored dashing criminals since Robin Hood, but the clever outlaw who assumes identities and profits from the trust of the innocent is an essentially American figure. Herman Melville's satire The Confidence Man is but the most prominent work in a genre concerned with the need to balance trust with caution.

Some approached this balance cynically, suggesting there's no difference between honesty and deceit. Bampfylde-Moore Carew said that everyone, deep down, is a fraud. He dared his readers, "Lay thy Hand on thy Heart and consider if thou hast not impos'd upon Mankind." Dishonesty, he suggested, is the universal condition of humankind:

Perhaps my Reader is some Gentleman of the Law, if so, let him consider ...if he never took in Hand a bad Cause, and assur'd his Client of the Goodness of it...Perhaps some plodding honest Tradesman is reading my Memoirs ...but he must be much better than his Neighbours ...if he has never put off a bad Commodity for a good one, or made his Goods weigh heavier than when he bought them. In a Word, most gentle Reader, every Profession has its Fourberies and Impostures; even the Printer of these Memoirs intends to print them on a large Letter, and with a broad Margin, ...to make thee pay the more for them.By this logic, Carew's impostures were no different from American life in general: all appearances are put on to win people's trust; everyone is an impostor.

But most people

recognized that, however thin the line may be between legitimate reinvention

and deception, it is real; that one is a virtue, the other a vice. And much of

America's story from the colonial era to the present is about working to

distinguish the two, trying to preserve what is valuable about self-creation

while warding off those who would take advantage of it.

![]()

Jack Lynch, author of The Age of Elizabeth in the Age of Johnson (Cambridge University Press, 2003), is associate professor of English at Rutgers University in Newark, New Jersey. He contributed to the winter 2005 journal a story on the meaning of the phrase "the pursuit of happiness."

Suggestions for additional reading:

- Carl Bridenbaugh, "'The Famous Infamous Vagrant' Tom Bell," in Early Americans (New York, 1981), pp. 121-49.

- Steven C. Bullock, "A Mumper among the Gentle: Tom Bell, Colonial Confidence Man," William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser., 55, no. 2 (April 1998): 231-58.

- Larry Cebula, "A Counterfeit Identity: The Notorious Life of Stephen Burroughs," Historian 64, no. 2 (winter 2002): 316-33.

- Daniel A. Cohen, Pillars of Salt, Monuments of Grace: New England Crime Literature and the Origins of American Popular Culture, 1674-1860 (New York, 1993).

- Gary H. Lindberg, The Confidence Man in American Literature (New York, 1982).