Page content

Working in Harness

The Saddler's Shop

Text by Ed Crews

Photos by Dave Doody

In the Taliaferro-Cole Shop, from left, Eric Myall, Jim Kladder, Jim Leach, and Jay Howlett make and repair saddles and harnesses.

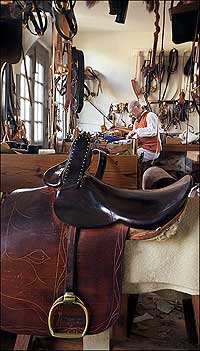

Jim Kladder stitches a piece, a finished lady's sidesaddle in the foreground. Few women, and those only of the highest class, rode.

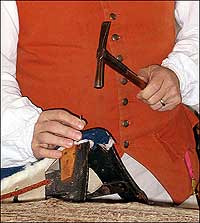

Using a double creasing iron, Myall adds an ornamental line to a harness strap. When heated, the iron leaves a dark line in its wake.

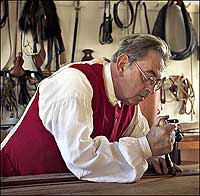

On the pigskin handle of a long driver's whip for a two- or four-horse carriage, Kladder smooths the stitched seam with a piece of bone.

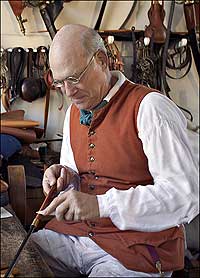

Howlett "round closes" a fire bucket with an awl and thread made from hemp. A flexible boar's bristle is attached to the end of each thread to help stitch through the tough leather.

A skillful saddle and harness maker with an ingratiating manner and a head for business could earn an excellent living in colonial America. His clients typically were rich and typically wanted the best. In the eighteenth century, supplying "the best" to the equestrian set usually meant comfortable profits.

For that you have the word of Jim Kladder, who oversees saddle and harness making in Colonial Williamsburg's Taliaferro-Cole Shop. Kladder says: "Horses were not as common as people think. They were expensive. Originally, owners had to import them, as they weren't native to this part of the world. The more horses you owned, the more the costs went up. Some Virginia planters had as many as six horses. Owners kept horses for various reasons, like riding, racing, and breeding. Almost always, saddle makers dealt with the 'carriage trade.'"

In British North America, customer relations were a function of personality and the ability to "read" people. And, like all eighteenth-century crafts, mastering the skills to produce saddle and harness, the system of straps connecting an animal to a vehicle, was the product of a lengthy apprenticeship in cutting, stitching, and assembly that usually began around age thirteen.

Among the skills the apprentice had to master were the uses of the special knives saddle makers cut leather with. The round knife, which has a half-moon blade, was particularly versatile and important. According to Colonial Williamsburg apprentice Jay Howlett, it still is.

"I often tell visitors I have three tools that I use on every job. The stitching awl, round knife, and dividers," Howlett says. "The round knife is a bit tricky at first but irreplaceable once you are accustomed to it."

Craftsmen cut leather following measurements or a pattern. Shop masters zealously guarded their patterns because they set his goods apart from the competition's. Patterns typically were made of wood or leather, and occasionally from paper, which was expensive. Masters started apprentices on small jobs working with small pieces of leather. That kept expenses low when the inevitable early learning mistakes occurred.

Apprentices began their training in stitching by producing the thread that a shop would use. It often was made from flax or hemp, which was coated with beeswax. Craftsmen used steel needles as well as tools that could punch holes in leather or slit the material. They also employed a "clam," a clamp that held leather, but left hands free to stitch. When it came to stitching leather, craftsmen often worked hard to produce a neat and attractive effect known in the trade as "finish." Finish reflected pride of craft, skill, and a thorough knowledge of the material.

Saddlers did not make the wooden tree or frame—the skeleton—of the saddle. They came from frame makers who lived in the colonies, or England, concentrated in Lancaster. English producers considered beech wood particularly fine saddle-tree material. Frame makers covered the tree with cheesecloth to prevent spitting. Saddle makers bought the frames and assembled the components on them. That assembly added up to a product.

An accomplished saddle and harness maker needed a deep, intuitive understanding of leather. This knowledge, known as a "good hand," was not so much learned as absorbed. The absorption could take years and could require a leather craftsman to handle hundreds, maybe thousands of hides. The hides could vary in appearance, strength, and grain, depending on the animal and the tanning. Leather could be stiff or soft, smooth or rough, waterproof or absorbent. Colors varied from white to red, black, and tan. Dyes could expand the palette. An apprentice came to appreciate the potential in each piece of leather he touched.

With an appreciation for a piece of leather's potential uses, a craftsman would know what type of hide to employ for a particular product. For example, hunters bounding through fields and forest wanted a "good seat" that helped them stay in the saddle. Hog skin was appropriate because its texture provided a good grip. Steer hide was less desirable as it became slick with use.

There were sidesaddles for ladies, postilions used by carriage drivers, portmanteaus for luggage, and racing saddles with pockets to add weights to handicap jockeys.

Making and repairing saddles and harnesses could provide success and status for the right fellow. Alexander Craig, one of the most successful craftsmen in the history of Williamsburg, was such a man.

Believed to be from Aberdeen, Scotland, Craig appeared in Williamsburg records during 1748, and died in 1776. He took a wife, and they brought six daughters into the world, all of whom married well. He enjoyed a reputation as an energetic and honest entrepreneur. Historians know a lot about Craig because his ledger and order book survive.

About 60 percent of Craig's work involved repairing saddles and harnesses. He also sold imported goods, ran a carting business, and made such items as collars for dogs, bear, and deer.

Today, much of Colonial Williamsburg's interpretation of the saddler's craft is based on information about Craig, Kladder says. At the Taliaferro-Cole Shop, Kladder, apprentice Howlett, and journeymen Jim Leach and Eric Myall have created an atmosphere that might make Craig or any eighteenth-century master feel at home the moment he walked in the door.

He'd notice the tools he used, rolled-up hides, finished and partially finished leather goods, and scrap baskets filled with bits of leather, because nothing is wasted. For that matter, a modern day maker of saddles and harness probably would feel the same way, because little has changed in the trade during the past two centuries.

"Saddles still are made by hand today," Kladder says. "The tools are virtually the same. Saddles and harnesses simply do not lend themselves to industrial production."

With traditional tools, techniques, and materials, the shop's craftsmen produce goods for other museums, as well as Colonial Williamsburg. They've made items for Mount Vernon, the Museum of the American Frontier, Patrick Henry's home, Red Hill, and the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library and Museum.

The shop works closely with Colonial Williamsburg's coach and livestock program, and has produced harnesses for two riding chairs manufactured by the wheelwrights. It also makes items for other Historic Area trades, including leather parts for bellows, lathe belts, and aprons. Repairs go on throughout the year, but the shop does most maintenance and production during the first quarter.

Howlett says he is attracted to the variety of the work and the detailed execution that comes from research and hands-on experience. Leach likes the connection to master craftsmen of the past. "I enjoy more than anything being able to examine original pieces and then being able to make an exact copy using the same methods as our predecessors," he says "It keeps you motivated, going, and eager for more."

Kladder has another reason. "Williamsburg is a great place to practice the craft. Look outside," he says, pointing out the window over his workbench at a carriage rolling down Duke of Gloucester Street, "and you can see your handiwork every day."

Ed Crews contributed to the winter 2003-2004 journal a profile of the foundry trade and an article on tavern music.