Page content

Jamestown Revisited

by Ivor Noël Hume

We had been possessed with a vague idea that we were going somewhere on a spree and until that moment had not realized the fact that we were on a pious pilgrimage to the birth-place of a mighty nation.

—David H. Strother, May 12, 1857

"Compared with the ruins of ancient Egypt, the ruins of Jamestown are humble," William and Mary professor and artist Louis Hué Girardin wrote shortly before the 1807 centennial.

The approach of Jamestown's four-hundredth birthday in 2007 renews in some an interest in the last centenary, the celebration of 1907, and all its failures and all its successes. It puts a mind to wondering, too, how Virginians saw their past in the century before—on the 150th anniversary, in 1857, and during the bicentennial in 1807. How well remembered was John Smith or Pocahontas then? To what extent were Jamestown and its ruined church icons of Virginia's colonial history? Less and more than you might suppose.

In 1707, Virginia's first centenary, the colony looked to a future in a new seat of government, and away from the first, ruinous Jamestown. Much of Jamestown had been destroyed during Nathaniel Bacon's 1676 rebellion, and although much had been rebuilt, the burning of its new statehouse in 1698 was the straw that dislocated the camel's back. Seventeenth-century hardships and disappointments were to be forgotten. England's new king, William, had disposed of the religious uncertainties of the reign of James II. An endowed college had been built in what had been Middle Plantation, a scattered community now being supplanted by the skillfully and formally designed new capital named for the sovereign, Williamsburg. Seventeen hundred seven, therefore, was not a year for wistful retrospection.

One hundred years later the youthful United States could congratulate itself on its achievements. It had earned its place in history, the appreciation of which invited an imagining of its rustic roots. At least it did for Professor Louis Hue Girardin at the College of William and Mary, who apparently had plenty of time for pedagogic speculation. On January 30, 1804, a new law student said he did not find the school "in so flourishing a Condition as I had anticipated."

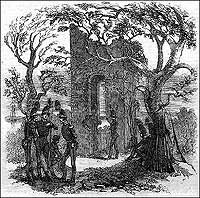

In August, Girardin took a small board and inscribed on it, in Latin, a recognition of John Smith's role in the colony's creation. This the professor took to Jamestown and hung on a tree branch overlooking the James River. While there he contemplated the "venerable ruins of the old church steeple, from the top of which venerable garlands of smilax, ivy, and other climbing and saxatile plants hang in irregular festoons." Compared with the ruins of ancient Egypt, he said, "The ruins of Jamestown are humble and inconsiderable, nor do we tread on 'Classic Ground.' Yet the emotions which the aspect of those national vestiges conveys to the soul, are powerfully enthusiastic, rapturously melancholy."

Girardin wrote this—and more like it—as a preface to a novel titled The First Settlers of Virginia, by one J. Davis, which was published in 1804 and republished in 1806.

The second edition included reviews of the first. A "young Virginian gentleman studying at Edinburgh" called the author a pedagogue whose style "is made up of pedantry, vulgarity, affectation and conceit" and said, "We never met with any thing more abominably stupid than this romantic legend about the Princess Pokahontas." Other reviews were kinder. One from the office of the president said Thomas Jefferson "has subscribed with pleasure to his Indian tale." It is evident that the legend of Pocahontas saving John Smith was already deeply ingrained in American lore.

While Davis's book was still available from his publisher at "No 1. City-Hotel, Broad-Way, New York," Virginians were preparing for the first Jamestown Jubilee, which, like the planning a hundred years later, was launched through a Norfolk-based select committee. A flotilla of sailing ships lay off Jamestown Island. The Norfolk artillery company fired salutes; there was a tented bazaar adjacent the church ruin, and College of William and Mary students practiced their oratorical skills. There were plantation balls in the course of a celebration that lasted the best part of five days. How many history buffs participated is uncertain, but the select committee reported "several hundred" when all had been done and said.

Preparing for the 1907 celebration, the planners looked to 1807 and reminded themselves that it had been a "period of pandemic patriotism" and that the fledgling United States had been twenty-six years old. Among the 1807 celebrants had been men who fought alongside George Washington and voted in the colonial General Assembly for Virginia's Bill of Rights. For them and their sons, 1807 had been the first opportunity to commemorate their accomplishment. Fifty years later, although the immediacy and the congratulatory fervor were long gone, Virginians were complacently proud that theirs was the state where it all began. It was time for another commemoration, this one organized by the Virginia Historical Society

An artist and writer for Harper's Weekly who went by the pseudonym "Porte Crayon," but whose name was David H. Strother, skillfully and engagingly captured the mood and spectacle when, on May 13, 1857, Jamestown Island was roused from its sleep by 6,000 guests. Like so many serious visitors to historic places, Strother wished he had not arrived as part of a group. "How we did wish, all those people were elsewhere enjoying themselves, that we might have this day among the tombs," he wrote. Then he said, "Doubtless there were thousands who joined us in that egotistical wish."

While Strother and a few other early arrivals were trying to read inscriptions on the time-worn tombstones, they were joined by what he called "the bone and sinew," who he thought were crewmen from one of the boats in the flotilla that lay offshore.

"Well, dear me," said one, "this is the place we've come to celebrate, is it? And here's where they were buried? They say it was a hundred years ago." "Two hundred and fifty years ago," said another. "Well, to be sure that's a good while, so I'll just take a bit of this 'ere tombstone as a 'momentum' of it."

So saying, the speaker cracked off a suitable chunk from one of the slabs. The others contented themselves with a brickbat a piece, and having pocketed their sentiments went their way toward the camp.

A large military camp lay downriver, and upstream, adjacent to what, less than a decade later, would be a Confederate fort, stood marquees and stands for dignitaries, college personnel, and Williamsburg citizens. In the fifty years since the previous celebration, when the island, mostly farmland in those days, could be reached only by boat or across an eroding causeway often submerged at high tide, a bridge had been built across the back river. It completed a straight path to the ruined church and remained the termination of Jamestown Road from Williamsburg until 1955, when National Park Service preparations for the 1957 celebrations included rebuilding the causeway and removing the bridge.

Artist Strother had arrived the old-fashioned way, up the James aboard the steamer Norfolk, and had been rowed to a landing below the church. Walking toward the tent city, he met an elderly black man mending a fishing net and apparently showing little interest in the boatloads of happy celebrants or the martial music from the military encampment. Their conversation has come down to us as a surprising vignette from the last days of slavery. But before I quote the exchange, it is pertinent to know a little more about the man who called himself Porte Crayon.

The broken remains of the church tower at Jamestown were one of the few above-ground relics of early settlement there. -Image Alchemy

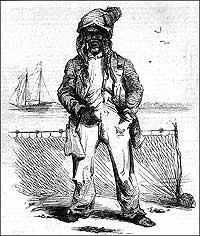

Strother met "Uncle" Lewis during the celebrations, just a few years before slavery came to an end. -Image Alchemy

Strother was born at Martinsburg, now in West Virginia, in 1816 into a farming, slave-owning family. Opposed to secession, he served as a Union army general. In the years before the Civil War he used his Harper's Weekly platform to take every opportunity to portray slaves as content and loyal to their masters—as some doubtless were. The net mender clearly was one.

"Good morning, Uncle," Strother said, "will you just stand still for a few minutes until we take your portrait?"

As the sketching progressed, the old man appeared increasingly uneasy, prompting the artist to ask whether he was tired. "No, Sir," he said, "not tired; but I was thinking of my master's business."

"And pray, what pressing business can one of your age have?" Strother said.

"I must finish mending my nets, Sir, and then catch some fish for my master's dinner."

As he continued sketching, the artist kept talking to hold the old man's attention, assuring him that as a fisherman he was emulating some of the biblical apostles, to which the net mender said:

"True, Sir, it was; as they in their high calling served our heavenly Master, so must I, while on earth, and in my humble way, serve my earthly master; 'for he that is faithful in that which is least, is also faithful in much.'"

To this Strother asked a question so patronizingly racist that anyone hearing it today would cringe in embarrassment: "So, Uncle, you expect to go to heaven when you die, and perhaps be white?"

"In that world, master," he said, "our souls will be white or black according as we have done our duty upon earth."

Strother asked him his name.

"Lewis Gilchrist," he said, then spelled it deliberately and correctly.

"Uncle Lewis," Strother said, "we have been wanting in respect to merit concealed under a rude exterior. You are a better Christian than we—perhaps a better man."

Gilchrist shook his head and smiled. Unlike thousands of others whose names and faces went with them to the grave, he looks out at us from the sketch more than a hundred years later.

His drawing pad temporarily put away, Porte Crayon continued in the direction of the action.

There were white pavilions for the ladies, booths for refreshment, kitchens, a stand for the speakers, and an extensive camp of the military from Richmond.... Drums were beating, colors flying, pots boiling, and glasses rattling; gallant looking officers on horseback, were galloping about the field; companies of soldiers were marching and manoeuvring; while the great unorganized multitude just swarmed about the pavilions, without doing anything in particular that we could conceive.

To get a better view, the artist climbed a tree and settled down thirty feet up. He could see a military contingent from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, "which demonstration from a sister state was well received and was one of the marked incidents of the day." It would be repeated more substantially in 1907 along with grandiose representations, among them buildings, some extant, from the other old colonial states.

The keynote speaker was former President John Tyler, who came from his nearby plantation, Sherwood Forest. William Clopton helped his father, elderly Judge John B. Clopton, an early Virginia Historical Society vice president, toward the dais. The ground was rough, and the day was warm, and Judge Clopton struggled. He kept asking his son to "take him to the stand." When they reached Tyler's platform, Judge Clopton said again, "Take me to the stand." His son said, "Father, we are at the stand. Here's Mr. Tyler about to speak." A little irritably, the judge said, "Oh, I don't want to hear John Tyler now. Take me to the stand where the mint julep is." From the tree, Porte Crayon could not hear, but he assured his readers that those who could "were much edified and delighted." After Tyler's oration, someone read a poem written for the occasion, and Virginia's Governor Wise delivered "a brief but spirited conclusion" before reviewing the troops. With the show over, the crowd melted away, some to Williamsburg, but most back aboard the fleet of sailing and steam vessels anchored off the island. While being rowed out to the Norfolk, a man fell overboard "and was rescued with so much difficulty, it was ascertained" that he "had a brick in his hat, which he was carrying off as a memento of the celebration."

The Norfolk was the last vessel to leave, and as paddle wheels churned out into midstream, Strother watched the penultimate rays of the setting sun shining "full upon the face of the ruined tower, lighting it with a smile as of a grinning skeleton. Another moment," he wrote, "a gray oblivious shadow covered it like a pall."

A year later, another Harper's magazine writer of equally florid prose visited the island to experience the solitude that had eluded Porte Crayon. He had done his homework. Quoting John Smith, he recalled where "two rowes of houses of framed timber, and some of them two stories, and a garret higher, three large Store-houses, joined together in length"—stood, is thus in process of degradation by the waves, which have reached within a few yards of the ruins of the church.

Most of the village, he said, had disappeared, "and the rest is slowly but perceptibly yielding to the current." Perhaps in the hope some wealthy and patriotic magazine reader would come to the rescue, the unnamed writer said that unless protected by pilings or some other engineering resource, the ground on which the first successful American settlement had its center will have disappeared forever. It will be established on the map only by its bearings, as longitude and latitude fix the place where some gallant and richly freighted ship went down.

Fifty years later the supposed site of James Fort would, indeed, be marked on maps as being out in the river at a location having verifiable latitudinal and longitudinal bearings. Although the 1858 visitor rather pointedly observed that only "one-tenth of the sum secured by the efforts of women for the purchase of Mount Vernon would suffice to keep above water the soil of Jamestown," no clarion call to battle came from the ladies of Virginia—not then or even soon.

The Mount Vernon Ladies Association, founded in 1856, had one mission, to preserve the home of the Republic's principal icon. Scruffy John Smith was not in George Washington's league. Besides, there was nothing left of Jamestown but the ruined church tower, and its creeper-clad walls were as nostalgic a memorial to the first settlers as anyone could devise.

Then came the War Between the States and the desire to glorify more recent heroes. As the Harper's writer had predicted, the not-always-gentle lapping of the James River nibbled away at the island and would, unchecked, for more than thirty years. But when help did come, it fell once again to distaff patriots to take the lead.

At first, the ladies' concern was not for Jamestown but for Williamsburg's deteriorating Bruton Parish churchyard, to which end, in 1884, resident Cynthia Beverley Tucker Coleman formed the state's first preservationist group, naming it for her deceased daughter. She called it the Catherine Memorial Society and vigorously pursued its mission. Four years later, in Norfolk, another formidable lady, Mary Jeffery Galt, launched a more broadly based campaign under the banner of her Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities. The following year the groups joined "to restore and preserve the ancient historic buildings and tombs in the State of Virginia." The intent was to preserve standing structures, and had there not been a church tower standing at Jamestown, the outcome might have been very different.

In 1894, thanks to the APVA's urging, the federal government appropriated $10,000 to construct the kind of breakwater the Harper's writer had advocated. Although it took another six years to get the project under way, in 1900 and 1901 a protective seawall was constructed along the most threatened stretch of the island's shore. It was ready in time for the 1907 Jamestown Exposition, and it survives today, a century-old monument to its engineer-builder, Colonel Samuel H. Yonge.

Thanks to him, the church tower still stands. But nothing else is as it was in 1857, when Porte Crayon made his drawings. A brick plantation house that had been home to the eighteenth-century Ambler family, and that was then occupied by an overseer and some slaves, burned for the third time in 1895. Two empty houses beside the landing are gone, and lost to the river is a brick structure identified as the old magazine. Indeed, as the nineteenth century drew to a close, only the shells of the Ambler house and church tower remained to keep company with the perennially net-mending ghost of Lewis Gilchrist.

What he may think of the multimedia, crowd-grabbing extravaganza planned for 2007, he will almost certainly keep to himself.

View the Harper's Weekly pages about the 1857 celebration at Jamestown (PDF files).

-Image Alchemy

Williamsburg-based Ivor Noël Hume contributed to the summer 2003 journal "An Oyster's Tale."