Page content

Virginia’s Very Own Navy

by Edwards Park

Photo by Tom Green

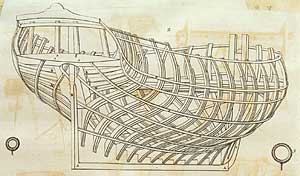

This drawing in William Falconer's Universal Dictionary of the Marine, 1780, exposes the complexity of ribs and beams beneath the sheathing of an eighteenth-century ship.

It is May 1776. Two bluff-bowed, armed merchant vessels crammed with troops, butt through the Atlantic near the end of a voyage from Glasgow to Boston. Each small ship carries a cargo of Scottish Highlanders, British soldiers shipping out to America to crush what now-after a year-appears to be a serious rebellion.

On a dank day off the Grand Banks a sail shimmers on the horizon. A smart little brig veers toward the transports, quickly overhauls them, and signals them to heave to and send their captains over to receive orders. This is their unlucky day-the brig Andrea Doria of the new American Continental Navy has captured them. The brig's skipper, Captain Nicholas Biddle, loads all 217 soldiers, plus many wives and children, aboard the transport Oxford, puts small crews aboard both his prizes, and heads for home.

Easier said than done.

Great Britain has reacted to America's revolution as any sea power would, with a blockade. It's pretty thin, for the British Admiralty hasn't yet beefed up its American Squadron. Thirty of His Majesty's warships are patrolling a coastline stretching from Florida to Nova Scotia. But they keep a tight hold on the much-used seaports of New England, the Chesapeake and Delaware Bays, and Charleston, South Carolina.

Biddle heads for Cape Cod, either to slip around into Boston or past it into Narragansett Bay. But off the shoal waters of Nantucket five British warships give chase.

Those odds are too tough. Biddle signals "disperse" to his prize crews and bears off in Andrea Doria. By the time he's evaded battle and coped with rough seas, he's lost contact with his prizes. And aboard Oxford those Highlanders-never a type to amicably accept forced restraint-realize that the warden of their floating prison is out of sight. They lose no time breaking loose. With the original British hands, they retake the ship from the small American prize crew.

Quickly, they change course for Virginia, for in its waters they may find Lord Dunmore, who has shifted the seat of Virginia's government from the Governor's Palace at Williamsburg to an armed vessel. He and his followers have been using it to disrupt the rebellion by harassing American ships, raiding villages of the Chesapeake Bay, bombarding Norfolk, and burning that city's waterfront.

The first sail the soldiers spot, however, is not Dunmore's. It's an armed vessel of the newly authorized Virginia Navy, under the command of James Barron. He spies the transport's British colors, raises an unofficial American flag, sweeps into range, and brings his guns to bear. His broadside crashes into Oxford.

The British instantly answer with well-served guns, and Oxford drives straight at the American ship, aiming to hook on with grapnels and board with cutlasses-and Highlanders. Captain Barron sees that the Britisher's deck is aswarm with 200 of the world's best troops, eager for a hand-to-hand Donnybrook. His own crew numbers less than seventy. He veers off, orders up chain shot for his guns, and looses the next broadside on his vessel's upward roll. Aimed high, his cannon tear up Oxford's rigging and bring down her mainmast. She's dead in the water with no choice but to strike her colors. Barron's prize crew sails her into Jamestown.

Photo by Dave Doody

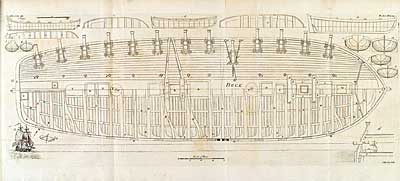

Thirteen wheeled canon bristle from the port side of a gun deck presented in Falconer's Dictionary.

Barron's victorious vessel was probably a brig, possibly a sloop. Her name may well have been Liberty. But perhaps it was Adventurer. Or Cruizer. Such uncertainties typify accounts of all our colonial-later state-navies, which sprang up soon after the shooting war started in Massachusetts. That spring of 1775, eleven of the thirteen colonies-all but New Jersey and Delaware-authorized their own navies to supplement General Washington's. While Continental ships were abuilding, the Virginia navy was in action, patrolling coastal waters, including the Chesapeake Bay.

Virginia's large fleet lacked today's public affairs officers, so its records are confusing. Its captains probably avoided publicity as assiduously as do twenty-first-century submarine skippers-partly because most American seafarers back then cut their teeth on highly competitive trade, partly because they faced the world's most powerful naval power, and the less the British knew about them, the better.

How in the world could a disorganized baker's dozen of separate colonies, strung along a thousand-mile coast, even pretend to rebel against a mighty nation on its way to becoming a huge and successful empire-especially since only about a third of those rebels really cared about rebellion?

Americans who served in Vietnam can attest that probably the most important military reason was Britain's inability to find and round up the full rebel force and bring it to a pitched battle. To the thousands of splendid British and German troops who were shipped to America, the assignment must have seemed a piece of cake: squelch a pesky uprising. But the rebels were unidentifiable, striking from ambush, then fading into the gullies and cliffs, the marshes and tangled forests. Through biting cold, smothering snow, flooding rains and howling tempests, while Britain's powerful and efficient army holed up in New York and Philadelphia and its mighty ships of the line swung at anchor, the rebellion went on. The war, one of the least popular in Britain's history, seemed endless.

The Royal Navy, with all its fleets totaling 130 huge line-of-battle ships and another hundred frigates, faced special frustrations. In 1775, its American Squadron was far too small to protect Halifax; rescue Boston, which was besieged by Yankee farmers; and maintain its patrol. And when it got into action, its captains soon learned that chasing an American vessel was apt to lead them into unmarked coastal shoals where the rebels knew every sandbar and reef. Though a British seventy-four-gun man-of-war could hurl tons of hot iron with a few of her broadsides, she wasn't much use when she ran aground. Anyway, she found few targets for her great artillery. A shipyard perhaps, or a coastal village-but there a bombardment might damage Loyalists as well as rebels. And it hardly seemed worth a twenty-four-pound ball to fire at a sneaky galley trying to row past in the dark with muffled oarlocks.

So, many a sleek Chesapeake Bay schooner, armed with a handful of six-pounder cannon, did run the blockade, easily outsailing the great ships and slipping away to the West Indies to trade tobacco for gunpowder-and cash or credit to support the Revolution. And if one of these elusive vessels captured a British merchantman on the way, so much the better for the Americans.

In Virginia, George Mason, author of the Virginia Bill of Rights, was so outraged by Lord Dunmore's fierce and unpredictable raids on Tidewater properties like his beloved Gunston Hall, that he set his people to building fast, shallow-draft vessels sturdy enough to carry a few guns. Mason was a strong backer of the Virginia navy, which was being debated at the Convention in Williamsburg. He hoped to keep the ex-royal governor out of the Potomac.

Like the new Continental Navy, Virginia's fleet was a hodgepodge of vessels, some enlisted from coastal trade, a few captured, many built beside the forests of oaks growing straight and tall around the bay. As those who sail the bay well know, the great estuary is tricky, a long, narrow, north-south waterway, quick to shoal near its shores, often the host of southwest or northwest winds. It was the same in earlier times, only cleaner and richer in seafood, and eighteenth-century boatbuilders were adept at turning out clean-lined sloops and schooners with the fore-and-aft rig that allowed them to sail close to the wind and change tacks in a flash. A ponderous square-rigger trying to sail up to Annapolis against a northwest wind had best drop anchor and wait for the breeze to swing around the compass. But an agile fifty-foot single-masted sloop or sixty-foot double-masted schooner simply sheeted home her sails, heeled down a bit, and tore ahead, spray flying. Armed with what guns they could carry, these speedy craft often slipped through the Capes and into the Atlantic for a little privateering.

Some larger vessels—two-masted square-rigged brigs able to carry more, and heavier, guns—took shape in the yards. Captured merchantmen could be converted there to ships of war. And a remarkable procession of small craft splashed off the ways in record time. Many were designated galleys, often with the lateen sails seen in the Mediterranean. As their name suggests, galleys were easily rowed with long sweeps if the wind failed-but almost all small vessels could be rowed when a ship's only power was God's wind and men's muscle.

Photo by Dave Doody

Virginia built warships at the Chickahominy River site

American naval tactics were simple: evade blockaders and keep trade alive, for it was paying the bills of revolution. Fight when you have a distinct advantage. As for tangling with a British warship, forget it. Those great vessels, bristling with eighteen- and twenty-four-pounders, were to be eluded, not fought. If you were trapped and faced with a final, desperate moment of truth, you struck your colors and steeled yourself to face British retribution: rotting in a prison ship, a moldy, rat-infested hulk anchored in the Hudson or Thames and forgotten by the world.

The Virginia navy found that the fortunes of war at sea often fluctuated as wildly as they had in the Oxford affair. Vessels were lost to the enemy, showed up under British colors, then recaptured. The Chesapeake tasted piracy as vessels raided plantations under pretense of patriot-or loyalist-needs. And in winter gales, the balmy West Indies lured captains from dull, cold duty.

In 1777, with France soon to become an overt ally of the infant United States, the Old Dominion dared send some ships across the Atlantic for trading. One was the brig Liberty, presumably the same vessel in which James Barron had dismasted and captured Oxford. Since then, the vessel had suffered problems with one of her captains, a man with the gentle name of Lilly, but not the personality to match. His warrant officers filed a protest against his "Arbitrary Tyrannical unmanly & illiberal behavior." His deportment caused so many seamen to jump ship that he ended up having to persuade four of those Scots Highlanders—now prisoners of war—that a career in the Virginia navy was exactly what they'd always wanted.

Now, Liberty went off to France under Thomas Herbert, called Silverfist because of the metal gripper that took the place of his left hand—presumably lost in action. The brig arrived in Nantes, unloaded 105 hogsheads of tobacco and 7,000 staves, and set out for some privateering in England's front yard. If John Paul Jones could do it, reasoned Silverfist, why not me? And indeed he took prizes, but he was maimed again in the process when one of his guns was dismounted by an enemy ball and broke his knee.

Silverfist was as tough as Lilly was nasty. But the outstanding captain in the Virginia navy was Barron. He came from an old Virginia family, and his career of commanding his state's ships started a family tradition of seagoing and naval service. He joined up on Christmas Day, 1775, as a captain, and by war's end he was serving as commodore of the Virginia fleet.

Barron was living in Hampton, his schooner Liberty—in those days that was a much-used name for vessels—moored near at hand. A nighttime gale tore in from the Atlantic, bringing with it a British schooner, Fortunatus, a large, well-armed vessel serving as tender for a frigate. Early in the morning she was spotted by Barron's brother, Richard, who mounted up and, acting the part of Paul Revere, galloped to James's house with the news that the British were not coming-they were here, and on the point of leaving.

James threw on some clothes and called up volunteers, who piled aboard Liberty, set sail, and overhauled the other schooner inside Cape Henry. Barron's guns were firing canister—bags of thirty-two musket balls—which savaged the British crew. Their captain, a brave Royal Navy lieutenant, agreed to strike when Barron put the matter to him. How they heard one another in the midst of such a conflict is ever a mystery to students of naval history. Liberty hauled alongside Fortunatus to board. The Americans found, in Barron's words, that "the Lieutenant and four men, were all the crew then able to use a sponge, or a rammer, to load a gun."

That spring of 1779 saw the arena of warfare shift from north to south. Because of poor management in faraway London, the British had bumbled their efforts to coordinate land and sea forces for a powerful offensive. Naval command in America had become a swamp of politics, and the war effort—despised in Britain anyway—seemed to grind to a listless halt. Then a new face appeared as acting CO of Britain's American Squadron. Sir George Collier wanted to hit the Chesapeake hard, wipe out its shipyards, and burn those cursed schooners. That would put a crimp in privateering and the tobacco trade.

Early in May 1779, Collier led a fleet of six warships, escorting twenty-eight troop carriers to Virginia. The ships swept between Cape Charles and Cape Henry and anchored as a thunderstorm roared around their masts. Next day the fleet steered to larboard through Hampton Roads and veered into the Elizabeth River past Norfolk. The troops disembarked: British redcoats, German mercenaries in their blue regimentals, and American Loyalists supposedly wearing green jackets, but often clad in whatever came to hand: 1,600 men in all, under the command of Brigadier Edward Mathew.

They captured Norfolk and Portsmouth and stayed in the area for two weeks, ravaging the shipbuilding industry which, in four years of war, had mushroomed, especially near the mouth of the bay. An unknown British source left a self-congratulatory description:

Night appeared grand beyond Description, tho' the light was a melancholy one: Five Thousand Loads of first seasoned Oak Knees for ship building, an infinite Quantity of Plank, Masts, Cordage, & numbers of beautiful Ships of War on the Stocks were all the Time in a blaze, & all totally consumed, not a vestage remaining, but the Iron Work, that such things had been.

Collier wanted to stay, bottling up the Chesapeake and devastating

every village up and down the bay. But General Clinton wanted Mathew's

troops back in New York, so the enemy fleet sailed north. The British

estimated the damage they had done at more than a million pounds sterling,

a hefty sum in those days. The Virginia navy licked its wounds and cleaned

up those of its vessels that had escaped by being deliberately sunk,

far up the rivers and creeks.

Britain scored heavily with this Chesapeake

raid and tried it again in late 1780. To reinforce this second raid,

the famous fighting general Benedict Arnold, who had just "turned

his coat" from the blue of the American Continentals to the gilded

scarlet of a British brigadier, arrived at the Capes with a small

fleet and a contingent of troops. They brought Arnold's brand of

warfare—daring strikes made with dazzling speed—to inland

areas by sailing up the James to plunder and destroy.

Mariner's Museum, Newport News, Virginia

The brig Andrea Dora is portrayed in action against an English counterpart.

Governor Thomas Jefferson reported to George Washington that "they landed at Burwells ferry below Williamsburg and near the Mouth of the Chickahominy," and a detachment of "the cowardly plunderers" entered Williamsburg. Richmond, recently made seat of government instead of vulnerable Williamsburg, was burned.

Driven far up the Chickahominy, Virginia's meager fleet was bottled up. A plan to torch Arnold's fleet with a fire ship, which Jefferson deemed a fine idea, stirred such excitement that word of it leaked out and the plan was regretfully aborted.

Inevitably, the Royal Navy cleared Virginia of rebel shipping, and the vessels that it missed sailed for the West Indies and Europe. In the summer of '81, as the veteran army of Cornwallis established a seemingly impregnable base at Yorktown, Captain John Cox, backed by St. George Tucker, raided Bermuda, cleaned out every grain of its stored powder, and deposited it in the Williamsburg Magazine. That was about the last important victory of Virginia's wartime navy.

For two years after the surrender at Yorktown, desultory warfare dragged on, and the French navy supposedly answered the need to safeguard trade. But American skippers found the alliance uneasy. All welcomed news of the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1783.

Barron held the rank of commodore until his death, four years later. His two sons were United States Navy officers. The younger, James, became a commodore himself, but was court-martialed. He'd commanded the frigate Chesapeake when the British Shannon inexcusably fired on her in 1807, forcing her to strike-an act of plain piracy that helped bring on the War of 1812. His son, another James, was made a midshipman at age three in honor of his father and grandfather.

Long-time contributor Edwards Park wrote "To Bathe or Not to Bathe: Coming Clean in Colonial America," for the autumn 2000 journal.