Page content

Peter Redstone Builds a Barton Portable

“You really can fall in love with the sound of harpsichord”

Text by Ed Crews Photos by Dave Doody

About sixty years ago, a small English boy fell in love with harpsichords. The relationship, however, began badly. The affair started during World War II, when the Germans were bombing Britain, and his hometown, Southampton, was a target. It was 1940 and Peter Redstone was four. Evacuated with other children to the safety of the countryside, he moved in with a wealthy lady in Westbourne. She owned a harpsichord, the first he’d seen. The keyboard instrument was so novel, so beautiful, so enticing, Redstone burned to see how it worked. He took it apart.

“I got caught doing it,” Redstone said. “I never forgot the punishment, or the fascination I felt for that harpsichord.”

Dave Doody

Redstone, right, and harpsichordist Michael Monaco, left, demonstrate the Barton’s portability in the backyard of the St. George Tucker House.

Dave Doody

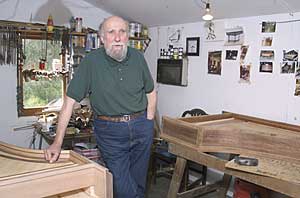

Redstone’s diminutive Claremont, Virginia, workshop gives him all the space he needs to plane, drill, and pound fine woods and brass bits into authentic re-creations of eighteenth-century harpsichords.

Dave Doody

Tensioning the harpsichord strings, perhaps a finer tuning job than a piano requires, makes the “Monaco sound” pitch-perfect.

During the next six decades, Redstone’s fascination became a passion and, finally, a vocation. Today, he builds and sells harpsichords for a living. The antique pursuit seems to fit perfectly the gentle, congenial nature of the now sixty-five-year-old craftsman. Six feet tall, thin, and bald with a white beard, Redstone has a soft voice and mellow English accent. The rough tones of Southampton were “beaten” smooth at the private and no-nonsense Bournemouth School.

He follows his trade in a cozy, bright workshop immediately behind his home in Claremont, Virginia, a James River community of one country store and 250 or so souls. The shop has one room with barely enough space for Redstone to squeeze around a half-finished instrument. The place smells of glue, varnish, and freshly cut wood chips. Often, as he works, Redstone takes inspiration from the recordings of music by such composers of harpsichord pieces as George Frideric Handel, Henry Purcell, and Domenico Scarlatti.

Here, Redstone has completed his eighty-fifth harpsichord, a commission from Colonial Williamsburg that required 400 hours of work, a reproduction of an instrument made by English craftsman Thomas Barton in 1709. Its acquisition was supported by a grant from the E. K. Sloane Fund of the Norfolk Foundation, which provides annual grants for the purchase and maintenance of keyboard instruments by charitable institutions. Established in 1950, the foundation is a permanent endowment used to help nonprofit organizations enrich life in Norfolk, Virginia, and surrounding cities, as well as to provide college scholarships.

Redstone’s Barton is comparatively small, light, and mobile and just the thing for special programming needs. To bring it to just-so perfection, Colonial Williamsburg’s staff harpsichordist, Michael Monaco, played it at every opportunity, adjusting, tuning, and making minor touch-ups.

“I give it two thumbs up,” Monaco said in an interview.

“For its size, it has no right to sound so good. Mechanically,

it works well. Its tonal quality is exceptional.”

Monaco is so struck with Redstone’s creation that he occasionally

will angle a telephone receiver toward the instrument and play

a tune or two for callers. Monaco is impressed not only with Redstone’s

creation but also with the sense of history and craft that motivates

and guides him.

“Peter really is a link to the past,” Monaco said. “He does everything according to the tradition and style of the 1700s. Nothing about his work is mass produced.”

The path in life that led Redstone to build Number 85 was long and twisting. After taking his punishment for disassembling the Westbourne harpsichord, he more or less focused on more appropriate childish interests until his teenage years. His fascination with the instrument was rejuvenated in school.

“I was in a music appreciation class, and I heard a recording of a piece by Handel played on a harpsichord. It was like getting hit on the head with a brick,” he said. “I was finished from that point on.”

Redstone wanted to make harpsichords. Finding a teacher, however, proved difficult. Harpsichords were popular from the sixteenth through eighteenth centuries. By the nineteenth century, though, the piano had overshadowed it. But the harpsichord never really disappeared and enjoyed a small revival in the twentieth century. So Redstone knew somebody was making them. He just didn’t know who they were or where they worked.

Unsure of how to get started in the craft, Redstone did a stint in the Royal Air Force, got electronics training, and eventually took a job with a fledgling computer company near London. He spent his free time touring the city’s museums, and he discovered Fenton House, home of an exceptional harpsichord collection. He also found a veteran harpsichord maker, Michael Thomas, who agreed to teach him the business. Redstone began dividing his time between twentieth-century electronics and eighteenth-century musical instrument making. Thomas taught Redstone a great deal. Redstone absorbed everything he could. In 1962, he began his first harpsichord, completing it in 1964.

Harpsichord making didn’t seem to offer long-term financial security. So Redstone took a job with RCA and came to the United States in 1967. He left that work four years later to follow his passion. During the 1980s, Redstone branched out, doing instrument repair and conservation work. That led to contacts with Colonial Williamsburg, which led to the Barton commission.

Harpsichord making has brought Redstone satisfaction. Demand for the instrument is steady but not spectacular. In a good year, he will make three instruments. Clients tend to be musicians who now find him via his website, www.ctg.net/redstone.

If harpsichord buyers are in short supply today, that was not the case in the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries, when harpsichord music, composers, and musicians were immensely popular in Europe. Historians know little of the instrument’s early creation or development. The oldest surviving harpsichord was made in Italy during the 1500s. Experts do know that the instrument became more complex and refined during the next two centuries. As it did, craftsmen began to build harpsichords with distinctive national characteristics in Italy, France, Germany, and England.

England proved a good home for instrument makers and composers. English lords and ladies owned and played harpsichords. Elizabeth I had one. The harpsichord’s popularity was as bright as its sound except for an eclipse during the killjoy rule of Oliver Cromwell.

Baroque composers played or wrote for the harpsichord. Handel was a superb player, as was Johann Christian Bach, son of Johann Sebastian Bach. One leading London harpsichord artist in the 1600s was court musician and composer Henry Purcell.

But harpsichords were expensive in Great Britain and its North American colonies. During the 1700s, Monaco said, most harpsichords in America were made in Great Britain. Because of the cost, the instrument was a status symbol. The powerful, the refined, and the wealthy made sure they had one in their homes.

Records show Virginia’s Governor John Dunmore owned one made by Jacob Kirkman, a craftsman so successful, he became rich. Thomas Jefferson owned one, which his daughter played.

Members of the early American upper class often mastered the harpsichord but were careful to play without polish. Style might suggest aspiration to professional musicianship, an unacceptable notion in a class-conscious age, which tended to look down on performers of all types, Monaco said.

Late in the eighteenth century the piano began its rise, partly because of the differences in mechanics. Harpsichords make sound with jacks that pluck strings. Pianos use hammers that strike strings. Pianos are more robust and powerful and have a greater range of musical possibilities.

Bartolomeo Cristofori of Florence, Italy, made the first piano in the early 1700s. John Isaac Hawkins of Philadelphia made the first successful low upright piano in 1800. The instrument, however, did not gain dominance over the harpsichord until roughly the 1830s. The harpsichord slid into obscurity during the nineteenth century, but found new fans in the twentieth.

The harpsichord is having a renaissance,” Monaco said. “It can bring a room to life. The harpsichord can transport people back to the eighteenth century.”

Monaco performs often at the Governor’s Palace, Geddy House, and other sites, so it is fairly easy to enjoy the lively, bright quality of harpsichord music throughout the Historic Area. He discovers the instrument connects easily with musicians, classical fans, and people who have never heard or seen a harpsichord.

“You really can fall in love with the sound of harpsichord,” Redstone said. “You just don’t find the same quality in a piano. I love Chopin, but piano music just doesn’t cause the same reaction in me that a harpsichord does.”

Redstone’s instruments are made using an authentic process and materials, including animal glue, iron strings, and oak and pine. He makes two concessions to the modern world. The jacks, which pluck the strings, are plastic; they originally were quill. The keys are made from synthetic bone instead of ivory. Redstone wants to save clients the endless maintenance that the use of such original materials would require. During the golden age of the harpsichord, he said, repairs and parts replacement took almost as much time as construction: “In the olden days, you fiddled with them constantly.”

Whenever Redstone begins a project, he thinks carefully about what the product will look and sound like when he is done.

“You need several skills to make a harpsichord,” he said. “Probably the most important one is having a vision you pursue about how the instrument will turn out musically as well as mechanically. You need woodworking skills and a good eye to look at the angles and to get something done right the first time.”

The Colonial Williamsburg project began with drawings that helped Redstone achieve a concrete vision of the product. When pressed, Redstone said he could make a harpsichord from scratch without plans. The sketches, however, allow him to explore details and refine them before the sawing begins.

Construction starts with Redstone gluing boards, assembling a frame, and putting veneer on the case. One of the most important steps, midway through the process, is creation of the soundboard. “It’s the heart of the instrument,” Redstone said. “It is made of thin pieces of spruce, which amplify the sound of the strings.”

Once the soundboard is done, keys are made, the harpsichord is strung, jacks are installed, and the stand and the lid are completed.

Watching Redstone work, you may at first think harpsichord making is little more than a sophisticated and specialized form of cabinetry. And it is true that the level of skill with tools and wood required here is great. Redstone’s vocation, however, is more than exquisite woodworking. It is art as well.

This is an art because there is no formula—simple or complex—for creating a harpsichord with great sound. The construction process always is basically the same, the stages following in a natural order, but the sound of the instrument is the product of thousands of tiny steps, decisions, and actions along the path to completion. It is impossible to gauge as the work proceeds the net effect of every saw stroke, spot of glue and veneer, and tautness of string.

“You really never know how a harpsichord will turn out until it is done,” Redstone said. “So many variables affect the final product. For example, just a few shavings off the soundboard can change the sound of the instrument entirely.”

He never is precisely sure when he will finish an instrument. That moment often takes him by surprise. The end comes without warning. The magic occurs almost instantly. When it does, a careful construction of wire, wood, and glue suddenly is a harpsichord.

“The end of a project simply comes,” he said. “It just sort of happens. When it does, I just start playing.”

Richmond writer Ed Crews contributed to the winter journal a story on Colonial Williamsburg’s youth interpreters program.