Page content

In "the country wherein it hath pleased the divine providence to appoint our lot,"

Early American Jews Found Freedom to Celebrate Autumn's High Holy Days

by Robert Doares

Interpreter Stephen Moore with a shofar, the ram's horn whose blasts ring out on Rosh Hashanah, the New Year's celebration.

Autumn, by the Common Era calendar, heralds the end of the year and the approach of Advent and the Nativity for Christians. For Jews, it signals the beginning of the year and the ten days of the High Holy Days—Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. Hanukkah, the Festival of Lights, comes at the end of the secular year but, in the Jewish calendar, about one-quarter of the way through the religious year, sometimes at the end of autumn, sometimes at the start of winter. Across time and geography, the principal autumn holidays have brought together for worship the devout and the less so and engendered a sense of Jewish community, no matter how dispersed its members.

Jews reached American shores with Columbus and slowly began a hemispheric diffusion. Most American towns and cities have a Jewish presence, though sometimes small. Settlement followed a similar pattern in most locales. The first resident Jews in a place joined in occasional meetings. As numbers warranted, they organized congregations. They generally established a cemetery, then a ritual bath, or mikvah. A house of worship was less important, because services can be conducted anywhere, even in an unconsecrated space.

How or whether Jews kept these holidays in the British North American colonies is a question. There is a general dearth of firsthand, English-language accounts of holiday celebrations among colonial Jews. Perusal of a most likely American Jewish archive, thirty-five letters written between 1733 and 1748 by New York wife and mother Abigaill Levy Franks, frustrates. We know the Franks family to have been devout and to have kept the Jewish holy days. Yet Franks's correspondence makes no mention of the family's holiday observances, only of the Sabbath.

Before we get deeper into the subject, a glance at the autumn holidays.

Interpreter Bereni New sets the table with a loaf of challah, the braided egg bread used for the Sabbath and the High Holy Days.

The Jewish liturgical year begins in early autumn with Rosh Hashanah—literally "head of the year"—the Jewish New Year. It celebrates the creation of the world and begins ten days of reflection and penitence called the "Days of Awe" or the "Days of Repentance." Rosh Hashanah's date—the first day of the month of Tishri—is fixed in the Jewish lunar calendar, which is based on the lunar cycle but adjusted by formulas to compensate for the shorter lunar month. It moves about in the Gregorian calendar. Like all days, Rosh Hashanah begins the evening before its calendar date, featuring a festive meal that includes a round, braided loaf, the challah, that represents the cyclical nature of life, the seasons, and the Jewish year.

Unlike almost all other Jewish holidays, the primary observances of the High Holy Days are in the synagogue, not the home. During the observance of Rosh Hashanah in the synagogue, the sound of the shofar, or ram's horn, calls the faithful to reflect on their deeds during the past year in preparation for repentance on Yom Kippur. Thus is Rosh Hashanah also known as the Day of Remembrance, when one's fate is written in the Book of Life. During Rosh Hashanah, Jews greet one another with the wish for a good year, L'shanah tovah.

Yom Kippur is the second of the High Holy Days. Called the Day of Atonement, it is a solemn fast day and the most important date in the year. Its liturgy is the longest of any of the holidays. As with Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur commences with a dinner before sundown on its eve. At the end of the meal, festival candles are blessed, and a twenty-five-hour fast begins for those over the age of thirteen. Families then go to the synagogue for worship. Likewise, they spend most of the following day in the synagogue, praying for forgiveness for sins of the past year, personal and communal, and resolving to carry out acts of tz'dakah, or deeds of righteousness, in the coming year. The appropriate greeting for Yom Kippur is G'mar chatimah tovah, "May you be inscribed for a good year in the Book of Life."

Five days after Yom Kippur comes Sukkot, or Booths, the harvest festival also known as Tabernacles to many non-Jews, the first of three agricultural festivals. It commemorates the wanderings of the Israelites through the desert in search of the Promised Land, when they lived in sukkot, temporary shelters. Following the biblical commandment to "live in booths seven days ...that future generations may know that I made the Israelite people live in booths when I brought them out of the land of Egypt," families build and decorate a sukkah at home. In it, they eat their meals. Depending on location and weather, some observant Jews sleep in the sukkah during the week-long holiday. Emphasis on fruits and vegetables in the decoration of the sukkah and in the meals reinforces the themes of abundance and hospitality in this harvest holiday. Services in the synagogue also mark the celebration of Sukkot.

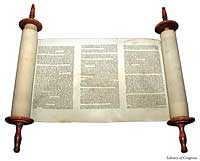

The autumn festival season ends with Simchat Torah, or Rejoicing in the Torah—the first five books of the Hebrew Bible. Though it comes at the end of the week of Sukkot, Simchat Torah is a separate holiday that celebrates the end of the yearly cycle of Torah reading and its beginning again. It is an occasion of joy and celebration, marked by the ceremonial reading of the final verses of the last book of the Torah, Deuteronomy, followed by the first verses of Genesis. Worshipers parade through the synagogue and dance with Torah scrolls.

The last holiday of the season is Hanukkah—also spelled Chanukkah or Chanukah, and meaning "dedication." Hanukkah lasts eight days, beginning on the twenty-fifth of the month of Kislev, which falls from late November to late December. The holiday commemorates the defeat of the Greek-Syrian King Antiochus, who outlawed Judaism and desecrated the Temple in Jerusalem, by the Jewish military heroes the Maccabees. Hanukkah recalls the rededication of the Temple after the Maccabees' victory.

The Talmud explains how a miracle gave Hanukkah its eight-day duration. When the Maccabees reconsecrated the Temple, they found enough holy oil to light the eternal lamp for one day. It burnt, however, for eight days, until more could be found.

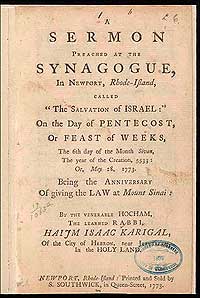

The first published Jewish sermon in the colonies was delivered by a visiting rabbi from Hebron, near Jerusalem.

Jews secured the right to practice their faith in many places under British dominion but not without generations of struggle. Varying degrees of religious toleration kept the number of Jews miniscule in most areas.

They had been expelled from England in 1290. Ferdinand and Isabella ejected them from Spain or forced them to convert to Christianity, beginning in 1492. A handful of conversos, as the often unwilling converts were called, sailed with Columbus.

Sir Walter Ralegh recruited Joachim Gaunse, a Bohemian Jewish metallurgist and mining engineer, for North Carolina's Roanoke Island colony in 1585. He is the first Jew in English North America on record. The earliest documentation of Jews in Virginia dates to the 1620s, when Elias LeGarde, Joseph Moise, and Rebecca Isaacke arrived.

Exclusion from the British Isles lasted until after 1651, when commercial policy prompted Oliver Cromwell to entice rich Jews from Amsterdam to London for the benefit of their trade interests with the Spanish Main. English restrictions on public worship and proselytizing continued until the 1698 Act for Suppressing Blasphemy made legal the practice of Judaism in England. There were 400 Jews in the country at the time.

Continental Jews had come to London, largely via Amsterdam, to escape persecution on the Iberian Peninsula and in Eastern Europe. Jews who fled Portugal after the establishment of the Inquisition there in 1536 came to be called Sephardic—Sepharad being Hebrew for Iberia—or Portuguese Jews. They spoke Ladino, a mixture of Spanish and Hebrew written in the Hebrew alphabet. Those who fled war and depredations in Central and Eastern Europe after 1630 were so-called Hoogduitse, or High-German, and Ashkenazim, Ashkenaz being the Hebrew word for the German lands. They spoke Yiddish, vernacular German mixed with Hebrew and Slavic elements and written in the Hebrew alphabet.

By the beginning of the eighteenth century, the two groups constituted a growing, if divided, Jewish community in London. Despite differences in language, culture, and socioeconomic backgrounds among the Jews, Christians tended to regard them as a single religious community. Considered as purveyors of useful capital and permitted to own land after 1723, Jews retained second-class legal status in England until the mid-nineteenth century. By contrast, in the 1740s, Jews living in the British colonies more than seven years could be naturalized.

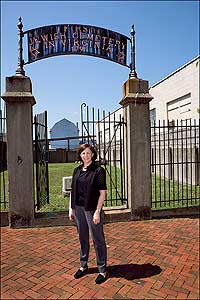

Bonnie Eisenman of the Beth Ahabah Museum stands in front of the oldest active Jewish cemetery of the South in Richmond.

Jews practiced their religion and observed their rites in eighteenth-century Britain. In 1708, French-born Protestant divine and historiographer Jacques Basnage de Beauval published in London an English-language edition of his History of the Jews, a long chapter of which detailed Jewish holiday practices. Basnage's work traced the origins of the holidays in ancient times and attempted to explain how aspects of the rituals had been modified during centuries of migration and life in the West.

Though Basnage composed his history with relative objectivity and benign curiosity, many of his contemporaries derided Judaism. In 1763, John Bilstone, chaplain of All Souls College, Oxford, published the sermon "The Ignorance of the Jewish Church, as to the Intent of their Institution considered." Bilstone regarded the Jews as a race of spiritual children, who would, in time, see their faith as a mere precursor to their adoption of Christianity. "With Regard to the Significancy of their Rites and Ordinances," he wrote, "and indeed the whole Body of Their Worship, 'tis evident these were but Types and Shadows of good Things to come."

In the British American colonies, Jews' ability to worship and to celebrate their holy days often depended on whether a community of Jews existed. The first Jews documented in most early settlements simply passed through.

When congregations formed in America, they benefited from their physical distance from the Old World and its biases and from their positions as co-builders of a new society alongside their non-Jewish neighbors. Settlement was under way by 1654 with the arrival in New Amsterdam, later New York, of twenty-three Sephardic refugees from Brazil. These established Kahal Kadosh—or Holy Congregation— Shearith Israel, the first such congregation in the thirteen colonies and the only permanent North American Jewish community of the seventeenth century. It is the oldest surviving congregation in North America. The New York congregation flourished, but other early American Jews remained itinerant, disconnected from worship other than private prayer, in part because of the requirement of minyan, a quorum of ten adult males for public services.

Though Jews arrived in Massachusetts during the seventeenth century, Puritan New England proved less attractive for them than other colonies. Most of the 250 identifiable Jews in the Atlantic seaboard colonies at the beginning of the eighteenth century resided in New York. Tolerant Rhode Island attracted Jewish families, as well, and the community there was large enough to commence building Touro Synagogue in 1759, the oldest surviving synagogue building in North America.

Pennsylvania practiced broad religious tolerance, but its oath of office kept non-Christians from public trusts through the mid-eighteenth century. Nevertheless, by the 1730s there were about a hundred practicing Jews in Pennsylvania, most in Philadelphia, some in outlying settlements. The Jewish population swelled to about a thousand during the Revolution. In 1782, the largely refugee community founded Congregation Mikveh Israel and dedicated the city's first synagogue on Cherry Street and Sterling Alley.

The Jewish presence in colonial Virginia was slight, but other southern colonies with liberal charters, particularly Georgia and the Carolinas, had large numbers of Jews among their early settlers. Forty-two Jewish immigrants to Savannah established Congregation Mickve Israel in 1733, and Charleston Jews founded Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim in 1750. Virginia's first permanent synagogue community, Kehilah ha Kadosh Beth Shalome in Richmond, coalesced after the Revolution, in 1789, but it is considered one of six colonial Jewish congregations along with others in Philadelphia, Newport, Savannah, and Charleston.

The parchment scroll of this late seventeenth-, early eighteenth-century Torah, probably from Amsterdam, contains the first five books of the Bible. The fall holiday of Simchat Torah celebrates the end of one year's reading and the beginning of a new one.

At least one eighteenth-century publication speaks to the degree of assimilation and openness of worship that Jews attained in urban colonial America. In 1766, a Dutch Sephardic scholar, Isaac Pinto, published a monograph called Prayers for Shabbath, the Beginning of the Year, and the Day of Atonements, According to the Order of the Spanish and Portuguese, with the Jewish calendar publication year 5526 on the title page.

In his preface, Pinto explained his rationale for producing an English translation of Jewish holy day prayers. He said many Jews had little or no understanding of the Hebrew words they uttered in prayer, so that "it has been necessary to translate our Prayers, in the Language of the Country wherein it hath pleased the divine Providence to appoint our Lot." He said Sephardic Jews in Europe had a Spanish translation of the Hebrew prayers, "but that not being the case in the British Dominions in America, has induced me to attempt a Translation in English, not without Hope that it will tend to the Improvement of many of my Brethren in their Devotion." Pinto's translation of the Sabbath, Yom Kippur, and other holiday prayers, printed in Manhattan by a non-Jew, would have been available to anyone in a country where was more frequently heard the greeting L'shanah tovah.

Robert Doares, an instructor in Colonial Williamsburg's department of interpretive training, contributed to the 2006 holiday journal the article "Wassailing through History."

Suggestions for further reading:

- The Letters of Abigaill Levy Franks, 1733–1748 (New Haven, 2004).

- Congregation Shearith Israel, the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue

- Jewish Encyclopedia

- Jacques Basnage and the History of the Jews by Jonathan M. Elukin