Page content

Tools for the Times

Modern Shop Reproduces Antique Implements

text by Ed Crews

photography by Tom Green

Guests rarely see Colonial Williamsburg's twenty-first-century toolmaking shop. Tucked in a corner of a modern maintenance area, it is out of the way, little known, not on tours, and seldom visited. But within its doors is a mechanical wonderland where craftsmen George Wilson and Jon Laubach use today's technology to accurately reproduce an array of eighteenth-century tools and objects. Historic Area interpreters use Wilson and Laubach's creations—saws, surgical instruments, surveying equipment, and apothecary weights, among other things—to make the colonial world come alive.

"We do things here that can't get done anywhere else. No museum in the world has a facility like this," Wilson said in an interview.

Jay Gaynor, director of Historic Trades, said, "We con-stantly will need new tools because we need to replace worn-out ones, we learn more about the tools we should be using, and we take on new technologies and projects that require new tools. Trades cannot fulfill its mission without historically accurate and fully functional tools."

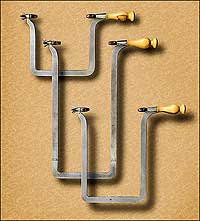

The Toolmaking Shop began operations formally in 1986. The early operation was modest. Today, it occupies a large, well-lit, comfortable space packed with power and hand tools, and raw materials. There are lathes, anvils, grinders, workbenches, clamps, saws, planks, and beech wood.

Colonial Williamsburg launched the shop as part of a 1980s initiative to upgrade the quality and authenticity of reproduction tools, Gaynor said. Nothing was readily available on the market. Historic Trades had neither the capacity nor the time to make such items. External vendors lacked the historical knowledge or were uninterested in the Historic Area's low-volume requirements.

"It was at that point that we realized a behind-the-scenes toolmaking operation would be the most practical, reliable, and financially efficient way to acquire the desired tooling," Gaynor said.

George Wilson, left, and Jon Laubach with a table full of saws in the modern shop where they make many of the tools for Historic Trades.

So Colonial Williamsburg called on Wilson and Laubach to start the project. They had ideal backgrounds. Both came to Williamsburg in 1970 as craftsmen. Wilson was the master musical instrument maker, Laubach a journeyman gunsmith. Wilson had proven his problem-solving and technical skills outside his area of expertise when he worked on the reproduction of a 1700s fire engine in the early 1980s. And he and Laubach tackled construction of a large cider press for Carter's Grove. Having worked with them, Earl Soles, then craft program director, knew he had the right men for the venture.

To anyone familiar with Historic Area trades, it may seem a little odd that their tools come from a modern facility. According to Laubach, though, no other practical solution exists.

"We need modern skills and modern equipment," he said. "There is no way we could supply the tools as quickly as they are needed or in the numbers needed if we didn't work this way. Understand, though, that we often cannot do a job entirely on a machine. We frequently rough out something on a machine and then have to finish by hand or make an entire item by hand."

Gaynor says their ability to do that is superb. It reflects their modern skills, mastery of eighteenth-century techniques, and appreciation for the form, function, and feel of antique tools.

"They both have excellent understandings of what eighteenth-century tools should feel like and their design and aesthetic qualities," Gaynor said. "One of the other problems we had with outside sources for tools is that with few exceptions, they didn't understand eighteenth-century tool design and aesthetic vocabularies, and what they made looked like something made in the twentieth century following a blueprint of an eighteenth-century object—maybe, to sum it up, too 'mechanical.'"

Laubach and Wilson often have to determine from scratch how a craftsman 200 years ago made something they want to reproduce. Sometimes their guides are an object or a period print.

"At times, there is a lot of detective work," Wilson said. "Often there's no record of how a craftsman did something. Tradesmen kept their practices secret. We have to do some reinvention to know how to do it today. This can involve some trial and error and a few blind alleys."

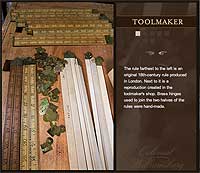

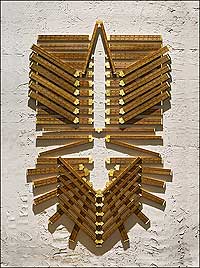

Boxwood rules in rows of stripes and chevrons, the metal stamps to mark the numbers and measures, the hinges, the pins, all handmade, each rule requiring twenty-five hours of work.

"We often learn as we go along," Laubach said. "We once had to make a marble mortar and pestle. Neither one of us had chiseled marble. So we had to learn."

Almost every new project, no matter how superficially simple, brings a set of complex issues. For example, Wilson and Laubach recently began making twenty-four-inch folding rulers known as "rules" in the 1700s.

A folding rule is a low-tech object as common in colonial times as in our own. Making authentic copies, however, proved difficult. The two men began by carefully studying an original rule produced in London. They noted that the rule's eighteenth-century maker carefully marked the distance gradations. He paid less attention to numbering; several figures are askew.

The first challenge involved finding boxwood, the rule's basic material. In the eighteenth century, it was available and often underwent a long, careful drying process. Today, sources are limited. Williamsburg eventually found a suitable variety. Hinge components also had to be located, although the shop is hand filing the tiny attachments. Each rule requires guide pins to ensure the two folding arms stay snugly together when not in use. Given the thinness of the rule and the small size of the pins, it takes careful placement and fitting—time, patience, and attention to detail. Each rule can require about twenty-five hours of work.

"These rules really were challenging due to the detail and accuracy required. We had to be consistent with the graduated measurements of the rule—all of which had to be done by hand," Wilson said.

Laubach and Wilson work to imbue everything they make with the look, feel, and spirit of eighteenth-century America. That's reflected in all they do, in ways large and small, in every item that goes out the shop doors.

"We want every item we make to look like it came from the colonial period," Laubach said. "We even look for tool marks left by the original craftsman. If that's what we see, then when an object leaves our shop, that's the way it will look."

Ed Crews, a Richmond-based writer, contributed to the spring 2006 journal an article on Colonial Williamsburg's basketmakers.

For further reading: