Page content

Christmas Trees, the Confederacy, and Colonial Williamsburg

by Harold B. Gill Jr.

Williamsburg's first Christmas tree, raised 163 years ago by Charles Minnigerode, portrayed by Tim Sutphin, at the Tucker House, may have looked something like the one at right.

The mists of memories shroud Colonial Williamsburg's St. George Tucker House, now a reception center and way station for donors.

In the spirit of Charles Minnigerode, each Yule season St. George Tucker House volunteers raise a Christmas tree for guests to enjoy.

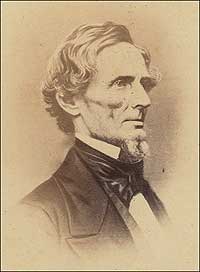

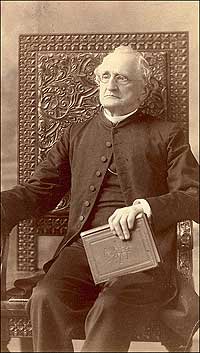

Captured here in the prime of his ministry, Minnigerode pastored at churches in Williamsburg, Norfolk, Prince George County, and Richmond.

NO ACCOUNT OF a Williamsburg Yuletide is satisfactory without the story of the city's first Christmas tree. At least the first the community's history records. Told now for 163 years, it goes like this:

European political refugee Charles Minnigerode moved to Williamsburg in 1842 to take up a professorship at the College of William and Mary. He became close to Judge Nathaniel Beverley Tucker, a professor of law, and boarded with him on Nicholson Street in what Colonial Williamsburg named, after the judge's father, the St. George Tucker House. At Christmas, Minnigerode entertained the Tucker children by sharing a homeland custom. They cut down a small evergreen, brought it inside, and raised it on a parlor table to decorate. There being no ready-made ornaments, he helped the children create their own, including popcorn strings. The next December, most Williamsburg families had Christmas trees in their parlors. A small tree, emblematic of the occasion, is now left each Yuletide on the Tucker House porch.

Who was this Minnigerode? What became of him? The story of his life is as interesting as the tale of his tree—even to the history of the restored colonial capital.

BORN KARL Minnigerode in 1814 at Darmstadt in the state of Hesse-Darmstadt, Germany, at fourteen he entered the Gymnasium, or high school, in Darmstadt, where he and the future playwright Georg Büchner met.

In 1831, Büchner entered the medical school at Strasbourg—the favorite city of expatriate German radicals, safely just on the French side of the Rhine. He became an intimate of the secret Society for the Rights of Man.

Hessian statutes required Büchner to complete his studies at a home university, which happened to be at Giessen. There, Minnigerode was studying law. They became the closest of friends.

It was the time of the rise of nationalism in Europe east of France. In the wake of the French Revolution, the values of liberalism and nationalism swept through Western Europe with Napoleon's armies. Those values found support among the small but growing urban middle classes, especially in the western German states.

Reaction inevitably set in, and those sovereignties reverted to feudalism. By the 1830s, free expression and liberalism had been killed. Enraged by the tyranny of the Grand Duke of Hesse-Darmstadt, Büchner formed a Giessen branch of the Society for the Rights of Man, and in 1836 wrote a radical pamphlet, the Hessian Peasant Courier. A police informant fingered the society. First arrested was Minnigerode, who had pamphlets in his possession. After a failed attempt to break Minnigerode out of jail, Büchner fled to Switzerland. In 1839, Büchner wrote:

Minnigerode is dead they tell me; that is, he was being tortured to death for three years. Three years! The French butchers got you done in two hours, first the judgment, then the guillotine. But three years! What a humane government we have, they can't stand blood.

But Minnigerode was alive. After eighteen months' confinement, he had been released under close surveillance. As soon as he could, he got to Bremen, where, September 1, 1839, he took a boat to America.

Minnigerode ARRIVED in Philadelphia in December and found a position teaching ancient languages and German. He anglicized his first name to Charles, and looked for work outside the German community. He saw an advertisement in a Philadelphia newspaper soliciting candidates for the chair of ancient languages at William and Mary and applied. He bested thirty other applicants. The college's board of visitors elected Minnigerode to the position in July 1842. George Blow, who supported applicant William Galt, reported to Galt's father:

Testimonials of about 30 Candidates were examined ...the Overwhelming Certificates, Letters of Recommendation and evidences of qualification, of splendid attainments and other requisites for a Professor, were so overpowering, that it left not a doubt or hesitancy in the minds of the visitors as to a choice, and on the first Ballot Mennigerode was elected...If Mennigerode deserves the tythe of what is said of him, he is one of the best educated men in this country, and unsurpassed as a Classicist, writing Hebrew, Greek, & Latin with perfect ease & elegance.

William and Mary President Thomas R. Dew wrote that Minnigerode "seems to be a very amiable little gentleman, & is deeply embrued with all the German literature." He became a popular Williamsburg citizen and an intimate of Judge Tucker's family, and made a literary name by publishing a series of articles in the Southern Literary Messenger on Greek drama.

Minnigerode had been in Williamsburg less than a year when he married Mary Carter, daughter of Commander William Carter. She was from North Carolina and likely not a member of the prominent Virginia Carter family. The couple married in Bruton Parish Church on May 13, 1843. They were so infatuated that Tucker wrote: "If they cannot break themselves of thinking there is nobody in the world but Mary and Cha-a-a rles (as she calls him) I could not bear to live in the same house with them." The Minnigerodes purchased the now-reconstructed east advance building at the Palace for a home.

A Lutheran, Minnigerode became an Episcopalian. In 1845, he submitted himself as a candidate for the priesthood. The following year Bishop John Johns ordained him to a Bruton Parish deaconate. He became a priest in 1847.

In the summer of 1846, Dew died. The visitors attempted to reorganize the school, causing faculty discontent. Most of it resigned, including the new president. The board decided to start from scratch, and in 1848 asked for the rest of the faculty's resignations.

Minnigerode accepted the pastorate of Merchant's Hope Church in Prince George County, where he remained until 1853, when he went to the Freemason Episcopal Church in Norfolk, the largest congregation in the Diocese of Virginia. In 1856, he was appointed rector of Richmond's St. Paul's Church, where he had occasionally preached as early as 1852.

In July 1852, Marianna Saunders of Richmond wrote her friend Sally Galt in Williamsburg that her mother wanted to go to St. Paul's because she had heard Minnigerode preach so often in Williamsburg that she wanted a change. She said:

Soon after we reached the church, who should come in dressed in his black gown, but the Minnigerode! I was de-lighted, for I never care to hear a more interesting preacher...It really did me good to listen to him preaching. I could almost imagine myself seated in our own quiet church.

Minnigerode stayed at St. Paul's for thirty-three years, years that embraced the War between the States, Reconstruction, and the rise of the New South.

IN 1860, England's visiting Prince of Wales attended a Minnigerode sermon. On Thanksgiving, a year later, Minnigerode conducted a solemn service for a congregation of Confederate walking wounded. Later he would say graveside rites at the city's Hollywood Cemetery for J. E. B. Stuart, commander of the rebel cavalry, and presided at the reinterment of President James Monroe in the same place, a graveyard that would be Minnigerode's place of eternal rest, as well as of his parishioner, President Jefferson Davis.

Richmond became the capital of the Confederate States of America on May 20, 1861, when the provisional Congress of the Confederacy moved from Montgomery, Alabama. St. Paul's stood, as it stands today, four blocks from the White House of the Confederacy, and across the street from the grounds of the new nation's capitol, a building states' rights advocates and presidents Thomas Jefferson and James Madison had helped design for Virginia's legislature.

When Davis arrived, he was feted with a Spotswood Hotel reception, where he and Minnigerode met. Minnigerode wrote:

Our acquaintance thus began, soon grew into friendly intercourse that became closer and closer, till an intimacy sprung up which ripened into companionship in joy and sorrow, and bound us together in the terms of mutual trust and friendship.

At the urging of Davis's wife, Varina, Minnigerode discussed church membership with Davis shortly after the inauguration. Minnigerode wrote:

He spoke very earnestly and most humbly of needing the cleansing blood of Jesus and the power of the Holy Spirit; but in the consciousness of his insufficiency felt some doubt whether he had the right to come...All that was natural and right; but soon it settled this question with a man so resolute in doing what he thought his duty. I baptized him hypothetically, for he was not certain if he had ever been baptized. When the day of confirmation came it was quite in keeping with this resolute character, that when the Bishop called the candidates to the chancel he was the first to rise.

Minnigerode maintained a close relationship with Davis, and his support of the Southern cause earned him such titles as Father Confessor of the Secession, Father Confessor of the Confederacy, and the Rebel Pastor. He wrote:

The secession of the Southern States was in defense of their constitutional rights, which were threatened by the aggressive and unconstitutional policy of the Government. That Government was a union of the separate Colonies as sovereign States, which delegated certain powers to the Central Government as the central agent of the sovereign States. The debate about their mutual relation was long, and the two views of the centralized union and a union of sovereign States existed from the beginning. But there would have been no United States at all if the State's rights had not been established by the Constitution.

His services were past standing-room-only popular. So many government officials attended that St. Paul's came to be called the Cathedral of the Confederacy. Diarist Mary Boykin Chestnut wrote that on a Sunday in March 1864 fourteen generals sat in Minnigerode's pews. Nevertheless, he attempted to walk a line between church and state. He said:

God forbid that I should speak as a mere man and not as the minister of Christ, that I should introduce politics where Religion alone should raise her voice, discuss measures and men where only principles can be laid down. It is as God's messenger that I speak and preach his gospel in faith, which is the alone principle that can steady our course and raise our hearts in hope. We preach to men under the circumstances in which we find them placed in God's providence.

Minnigerode often paid pastoral visits to the Davis household. But the parson wrote: "I never meddled with his policy or measures of his government; still less did I ever use his confidence for any personal purposes. Mr. Davis was not the man for that."

Minnigerode's oldest son, sixteen-year-old Charlie, entered the Confederate army without his father's consent and served on General Fitzhugh Lee's staff. Another son, James Gibbon Minnigerode, was a midshipman in the Confederate navy and participated in the Battle of Mobile Bay. After the war, he became an Episcopal minister, serving as rector of Calvary Protestant Episcopal Church in Louisville, Kentucky.

On January 1, 1865, when the future of the Confederacy was much in doubt, Minnigerode preached a stirring sermon at St. Paul's entitled, "He that believeth shall not make haste." He said to the congregation:

Reverses have followed us in many parts of our country, and the year opens with dark and threatening clouds, which have cast their shadow over every brow. What we need is a stout heart and a firm, settled mind: and oh! May we AS A NATION remember, "he that believeth shall not make haste...." I do pray and hope that God will have mercy upon us, and give us better minds and stout hearts and unfailing faith, that shall not make haste, that shall win the prize. But if we fall, let us fall with our faces upward, our hearts turned to God, our hands in the work, our wounds in the breast, with blessing—not curses—upon our lips; and all is not lost! We have retained our honor, we have done our duty to the last....

One Sunday a few months later, a messenger came in during the service and handed Davis a telegram from General Robert E. Lee at Petersburg. It said General Ulysses Grant had broken the Confederate lines and suggested the government abandon Richmond. Davis left the service and others followed. Minnigerode asked the rest to remain. After the city fell, he disputed with Union officials his right to lead St. Paul's congregation in prayer for the fleeing Davis.

Captured, Davis was imprisoned for treason—a charge eventually dropped—at Fort Monroe, Virginia, in solitary confinement. After petitioning President Andrew Johnson and Secretary of War Edwin Staunton, Minnigerode was the first civilian permitted to visit, allowed two calls a month, pledging his word of honor as a gentleman and Christian minister that in all the visits I am permitted to make to Mr. Jefferson Davis at Fortress Monroe, Va., I will confine myself to ministerial and pastoral duties, exclusive of every other object; that I will in no way be a medium of communication between the said Davis and the outer world; that I will observe the strictest silence as to the interviews, and will avoid all modes of publication, not only as to what passes between us but as to the fact of the visits themselves.

When Davis was bailed at federal court in Richmond, Minnigerode was at his side. After court, when they met at the Spotswood, Davis said, "Mr. Minnigerode, you who have been with me in my sufferings, and comforted and strengthened me with you prayers, is it not right that we now once more should kneel down together and return thanks?"

IN 1868, LEE, now president of Washington College in Lexington, Virginia—today's Washington and Lee University—asked Minnigerode to conduct the baccalaureate service. He continued as rector of St. Paul's, where, on July 14, 1868, he united in marriage Frank Goodwin and Letitia Moore Rutherfoord, who would be the parents of William Archer Rutherfoord Goodwin, later rector of Bruton Parish and co-founder, with John D. Rockefeller Jr., of Colonial Williamsburg. Young Goodwin was present when Minnigerode gave the invocation at the unveiling of the Lee statue on Richmond's Monument Avenue in 1890.

Minnigerode was appointed a William and Mary visitor. He retired from St. Paul's in 1889 and moved to Alexandria to become chaplain of Virginia Theological Seminary, which Goodwin entered in 1890.

Minnigerode died October 13, 1894. Granddaughter Marietta Minnigerode Andrews was an artist and author. Grandson Meade Minnigerode Jr. co-wrote the lyrics of the "Whiffinpoof Song" in 1909. Goodwin introduced to Colonial Williamsburg the custom of Grand Illumination in 1935.

Suggestions for further reading:

- Christmas Customs (will open in a new window)

- The Community Christmas Tree in America's Hometown

Listen to a Behind the Scenes Interview: Professor Minnigerode lights a tree. Bob Doares talks about playing the part of the German professor who brought the tradition of the Christmas tree to Williamsburg in the mid-19th century.

Listen (MP3, 2.8Mb) ||Historian Harold B. Gill Jr. is the journal's consulting editor. He contributed to the summer 2005 issue "The Exchange, Revisited."