Page content

War of Words

How the Stamp Act sparked the American Revolution

by Gordon S. Wood

Colonists expressed their displeasure with the tax in a variety of ways, including this button on which the No Stamp Act message encircles a portrait of British Prime Minister William Pitt.

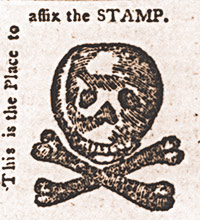

The 1765 Stamp Act created a direct tax of one penny per sheet on newspapers, which reacted angrily with a skull-and-crossbones protest stamp of their own.

When the tax was repealed in 1766, Landon Carter of Richmond County, Va., celebrated with a set of special teaspoons inscribed with REPEAL OF THE AMERICAN STAMP ACT.

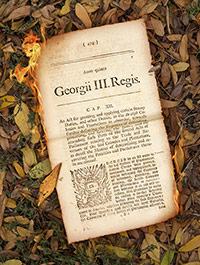

This year marks the 250th anniversary of the Stamp Act, the controversial tax imposed by the British Parliament on the American colonists in 1765. Levied on legal documents, bonds, deeds, almanacs, newspapers, college diplomas, playing cards — indeed, on nearly every form of paper used in the Colonies, the stamp tax ignited a firestorm of opposition that swept through the Colonies with unprecedented force. In each Colony, the stamp agents were mobbed and forced to resign. Except in Georgia, the law was effectively nullified before it could be put into effect.

The Stamp Act sparked more than riots and mobs. It precipitated one of the greatest constitutional debates in Western history. Much of the imperial debate was carried out in pamphlets — inexpensive booklets ranging in length from 5,000 to 25,000 words and printed on anywhere from 10 to a hundred pages or so. Easy and cheap to manufacture, these pamphlets were the instant media of their day, perfect for rapid exchanges of arguments and counter-arguments.

This dispute between the Colonists and Britons, and among Americans themselves, involved all of the fundamental issues of politics and government — power and liberty, rights and constitutions, popular consent and representation, statutes and fundamental law, and the problem of sovereignty. Once begun, this decadelong contest escalated through several stages until it climaxed with the Americans' Declaration of Independence in 1776. The argument was both exhilarating and eye-opening. It forced both the British and the Colonists to confront their differing experiences in the empire during the previous century, exposing divergences that had heretofore been largely hidden from view. By the time the debate was over, Americans had not only sharpened their understanding of the limits of public power, they had also prepared the way for their grand experiment in republican self-government and constitution-making.

The transatlantic discourse of texts published in Boston, Philadelphia or Williamsburg soon appeared in London and were quickly reprinted, and vice versa, triggering yet more pamphleteering. Printers and booksellers, often themselves political partisans, played a crucial role in these rapid-fire exchanges by preparing the works for publication, advertising them in newspapers, distributing them to subscribers and other book buyers, and posting copies to other vendors in other locales.

Although the print runs for these political pamphlets could be relatively small, often as few as 500 copies, their reach was multiplied many times over by their circulation in coffeehouses, clubs and other gathering places and by extensive republication in newspapers and periodical digests. The pamphlets concerned with the American controversy from both sides of the Atlantic numbered well over a thousand. Some were brief and inconsequential, but others important and breathtaking. A few of them — those written by Edmund Burke and Thomas Paine, for example — contain some of the most significant statements about politics ever made.

Once the British government sensed the stirring of Colonial opposition to the Stamp Act, it enlisted a number of English pamphleteers to explain and justify Parliament's taxation of the Colonies. Among them was Thomas Whately, the subminister who had drafted the Stamp Act. He argued that the Colonists, like Englishmen everywhere, were subject to acts of Parliament through a system of "virtual" representation. Even though the Colonists, like "nine tenths of the people of Britain," did not in fact choose any representatives to the House of Commons, they were, he wrote, undoubtedly "a part, and an important part of the Commons of Great Britain: they are represented in Parliament in the same manner as those inhabitants of Britain are who have not voices in elections."

During the 18th century, the British electorate made up only a tiny portion of the nation; probably only 1 in 6 British adult males had the right to vote, compared with 2 out of 3 in America. In addition, Britain's electoral districts were a confusing mixture of sizes and shapes, the complicated product of centuries of history. Some of the constituencies were large, with thousands of voters, but others were small and more or less in the pocket of a single great landowner. Many of the electoral districts had few voters and some so-called rotten boroughs had no inhabitants at all. The town of Dunwich continued to send representatives to the House of Commons, even though it had long since slipped into the North Sea.

At the same time, some of England's largest cities, such as Manchester and Birmingham, which had grown suddenly in the mid-18th century, sent no representatives to Parliament. Whately and other Britons justified this hodgepodge of representation by claiming that people were represented in England not by the process of election, but by the mutual interests that members of Parliament were presumed to share with all Englishmen for whom they spoke, including those — like the Colonists — who did not actually vote for them.

Americans immediately rejected claims that they were virtually represented in the same way that the nonvoters of cities like Manchester and Birmingham were. In the most notable Colonial pamphlet written in opposition to the Stamp Act, Considerations on the Propriety of Imposing Taxes (1765), Daniel Dulany of Maryland admitted the relevance in England of virtual representation, but he denied its applicability to the Colonies. America, he said, was a distinct community from England; it could not be represented by the agents of another community.

Others, such as the Swiss-born Georgian John Joachim Zubly, challenged the very notion of virtual representation. If the people were to be properly represented in a legislature, Zubly said, not only did they have to actually vote for the members of the legislature, they also had to be represented by members whose numbers were proportionate to the size of the population they spoke for. What purpose is served, asked another famous pamphleteer, James Otis of Massachusetts, by the continual attempts of Englishmen to justify the lack of American representation in Parliament by citing the examples of Manchester and Birmingham? "If those now so considerable places are not represented, they ought to be."

In the New World, electoral districts were not the products of history that stretched back centuries, but rather were recent and regular creations that were related to changes in population. When new towns in Massachusetts and new counties in Virginia were formed, new representatives were sent customarily to the respective Colonial legislatures. As a consequence, many Americans had come to believe in a very different kind of representation from that of the English. Their belief in actual representation made the process of election not incidental but central to representation. Actual representation stressed the closest possible connection between the local electors and their representatives.

For Americans, it was only proper that representatives live in the localities they spoke for and that residents have the right to instruct their representatives. Americans thought it only fair that localities be represented more or less in proportion to their population. Despite its shortcomings by today's standards, the Americans' practice of actual representation was the fullest and most equal participation of the people in the processes of government that the modern world had ever seen.

In 1766, Benjamin Franklin's testimony before the House of Commons (quickly published as a pamphlet) helped to justify Parliament's repeal of the Stamp Act. To cover its embarrassing retreat, Parliament also passed the Declaratory Act, which asserted its right to legislate for the Colonies "in all cases whatsoever." This was a robust assertion of parliamentary sovereignty — that is, the doctrine that there had to be in every state one final, supreme, indivisible law-making authority.

Although the Colonists had instinctively denied Parliament's right to levy an "internal" tax over them because they were not represented in the House of Commons, they were willing to admit the authority of Parliament to regulate their trade. After all, it had been doing so for a century or more. Mistakenly believing that this concession meant that they would accept "external" taxes levied on imports, British officials led by Chancellor of the Exchequer Charles Townshend in 1767 imposed levies on glass, paper, paint and tea imported into the Colonies. But the Colonists no more accepted these Townshend Duties than the Stamp Act, and they exploded once more in opposition with riots and nonimportation agreements.

It was left to John Dickinson, the most popular patriot pamphleteer of that decade, to explain in his Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania (1768) that America opposed all forms of parliamentary taxation, "external" as well as "internal" taxes. Still, Dickinson conceded Parliament's right to impose duties to control the flow of Colonial commerce but not to raise revenue; the intention behind the duty was crucial. By 1768, the Colonists were still trying to explain their previous experience in the empire, admitting that Parliament had some authority over the Colonies but not the authority to tax.

To counter all the Colonists' halting and fumbling efforts to divide parliamentary power, the British offered a simple but powerful argument based on the doctrine of sovereignty.

If the Colonists accepted "one instance" of Parliament's authority, then they had to accept all of it, wrote a sub-cabinet official, William Knox, in 1769 in one of the most important British pamphlets of the debate. And if they denied Parliament's authority over the Colonists "in any particular," then they must deny it in "all instances" — meaning that the union between Great Britain and the Colonies must be dissolved. "There is no alternative," Knox concluded. The Colonists were either totally under Parliament's authority or they were totally outside it.

Since tyranny in British history had always come from the Crown, good Whigs like Knox found it inconceivable that anyone in his right mind would want to escape from Parliament's libertarian protection. Many American Whigs who remained loyal to Britain in 1776 felt the same way. After all, Parliament was the august author of the Bill of Rights of 1689, the historical guardian of the people's property and the eternal bulwark of their liberties against the encroachments of the Crown.

Gov. Thomas Hutchinson, speaking to the Massachusetts legislature early in 1773, made the same argument as Knox had, and the response by the House of Representatives (this exchange was published as a pamphlet, one of the most fascinating of the period) was not what he expected. Given the choice between being completely under Parliament's authority or being independent, the House chose independence.

In 1774, in response to the Boston Tea Party, Parliament passed the Coercive Acts or, as the Americans came to refer to them, the Intolerable Acts. These closed the Port of Boston, altered the Massachusetts charter, modified judicial procedures and venue for trials, changed the rules for quartering troops, restricted the Colony's town meetings and appointed the commander in chief of the British army in America to be the governor of the province. These extraordinary assertions of parliamentary power convinced many Americans that the Massachusetts House in the previous year had been right and that Parliament should have no authority whatsoever over the Colonies. Prominent patriots, including James Wilson and Thomas Jefferson, wrote a number of important pamphlets in 1774 that set forth a radically new conception of the empire. Each of the 13 Colonies, they contended, was totally independent of Parliament, but each retained an allegiance to the king as the common link in the empire.

Because the Colonists by 1776 had concluded that they were tied solely to the king, their Declaration of Independence needed to break only from the British monarch. All of the indictments of British authority in the Declaration were leveled solely at King George III. "He has refused... He has forbidden... He has plundered..." went each of the indictments against George III. The Declaration never directly mentioned Parliament, even though it had been Parliament that enacted the Stamp Act, the Townshend Duties, the Coercive Acts and most of what the Colonists had objected to throughout the pamphlet debate. The closest the Declaration came to suggesting Parliament's participation was when it charged that the king "has combined with others to subject us to a Jurisdiction foreign to our Constitution." Since Jefferson and many members of the Continental Congress were lawyers, they wanted their declaration to be scrupulously legal and in accord with the imperial relationship they had arrived at by 1774.

With the issuing of the Declaration of Independence the extraordinary trans-Atlantic pamphlet contest of the preceding dozen years came to an end. Swords rather than pens would decide whether that independence could be sustained. From this rich imperial debate Americans thought they had learned how to make their own governments and their own constitutions, how to protect popular rights and liberty, and how to separate and divide the powers and spheres of government. But they soon realized that there were more lessons to be learned and the debate among themselves continued for another decade.

Gordon S. Wood is Alva O. Way Professor of History Emeritus at Brown University. He is the author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning The Radicalism of the American Revolution and editor of The American Revolution: Writings from the Pamphlet Debate 1764 -1776. Recently published by The Library of America, this annotated two-volume edition includes 39 of the best and most significant of these pamphlets — written by American Patriots, American Loyalists and Britons — which, together, chart the course of the war of words that preceded the War of Independence.