Page content

Native Numerals

Among American Indians, Numbers Counted for More than Math

by Anthony F. Aveni

Mattaponi Indian Sam McGowan notches a stick, a common way of counting among American Indians: the number of warriors slain, animal skins traded, the cycles of the calendar.

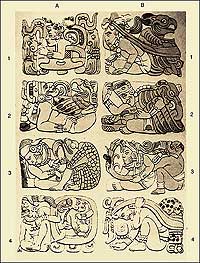

Human figures bearing animals are a Maya calculus of the time elapsed between the last creation and the current king's rule, a creation that cyclically regenerates itself with a new birth.

In Copan, Honduras, the Maya king appears on one side of a monolith. On the other side are Maya representations of time.

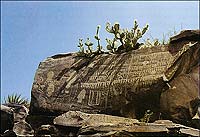

Tally marks—counting days or months, perhaps, or animals kills during hunting season—on a rock outcrop in northwestern Mexico.

Incas kept track of numbers, even transcribed their past, with knots on a string, called a quipu: "By the use of his quipu he could read off his history better and faster than a Spaniard with his book." The size and placement of the knots told the counts.

Notched counting sticks served as calendars for many Indian tribes—among them Powhatan, Chippewa, and Ojibway—often using a system of tens to group numbers.

To the Indian civilizations of America, North and South, numbers were more than abstractions. They had life and content. There were connections between measurement and things measured, a concept outlandish to the Europeans who came to colonize, and still curious to us.

I think it a pity that neglect of the view of those who would give life to number has stood in the way of scholars taking more seriously the study of mathematics in cultures other than our own. The American Indian was close to Pythagoras when it came to how numbers were understood. Yet we place little value on learning about Native American math, because it is not as sophisticated as the Old World's. Maybe instead of asking: "How were their numbers like those?" we might achieve greater knowledge by asking: "What did their numbers mean to them?"

A likely place to start looking for answers is with one of the hemisphere's most mathematically advanced peoples, the Maya.

It stands majestically erect in front of a stairway at the north end of a 300-meter long plaza together with a dozen other larger-than-human-size monoliths at the Maya ruins of Copan, Honduras. On one side the image of the great eighth-century king of Copan, Waxak-Lahun-Ubah-Kawil (wah-shóck-lah-hoón-oob‡h-kah-whéel), adorned in ceremonial costume and holding the implements of high office, looms in bold relief; on the other side eight neatly squared off hieroglyphic images confront the eye as it scans the stela from top to bottom—see opposite page. Each glyph depicts a humanoid figure who looks to be engaged in some sort of wrestling match with an animal—a bird in frame A2, a toad in A3, a tortoise in B1, an elephant-like creature in B2, a grotesque humanoid in B3, an amorphous mass—could it be the pelt of a jaguar?—in B4, and so on.

Look more closely at the imagery and you will see that the action is more akin to carrying. Each figure seems to be a porter caught in the act of transporting his animal. The men in frames B1 and B4 employ tump lines, common devices used by Maya peasants today for carrying a load of wood or a sack of grain by tying one's pack to a band that presses tightly about the forehead. That leaves the bearer's arms free to swing and perform other tasks as, hunched forward, he carts his burden. The porter in B2 cradles his conveyance under his arm, bearing most of the weight on his left shoulder. In B3, a youthful carrier grips his load by its ultralong deformed left limb, its talons protruding in front of the bearer's face. The old man in A2 almost seems to be making love to his avian cargo.

Maya epigraphers—those who decode script—tell us the porters are numbers. Number nine, which is B1, is distinguished by the markings on his youthful chin; he wears a jaguar claw for an earplug. Below him lies the number five, to the left of whom is the number fifteen. Just as five resembles fifteen when we speak it, so too Maya teen and ordinal numbers are near look-alikes. Five and fifteen wear the same cap, except that the fifteen's jaw is without flesh. The pair of bearers in row three is also identical. The telltale hand over the jaw indicates that they are zeroes, symbols of completion of a cycle. That is quite a different concept from "emptiness," which is the way we think of zero.

What burden do the Maya number gods carry? Time—1,405,800 days' worth of it—approximately 3,851 of our seasonal years, the duration between the last creation of the world and the date the monument was set in place to honor a ruler the citizens of Copan believed descended from the gods. His titles and major accomplishments—conquests, accession to office, marriage, etc.—take up the rest of the space on the stela, and on most of the monuments that share the space on Copan's North Plaza.

Place value and the concept of zero are two advanced features that the Maya number system shares with our modern Arabic notation. But Maya numbers were written vertically, with place value increasing from bottom to top, and the base of the system was twenty instead of ten, making the higher places 20, 400, 8,000, 160,000, and so on, rather than 10, 100, 1,000, 10,000, and so forth.

When counting time, however, like their counterparts in the ancient Middle East, the Maya developed a variant of this system. They altered the third place to 360; the fourth became 20 x 360, etc. This so-called vigesimal system presumably originated from the prenumerate habit of counting digits on both the hands and feet. It seems reasonable that such a system would develop among tropical cultures, where most people go barefooted. For us time is linear, like an unending thin wire studded with beads that represent events—Columbus's landing October 12, 1492, President Kennedy's assassination November 22, 1963, the 9/11 attacks, and so on. But for most Native American cultures, from the Hopi-Navajo to the Inca, time is cyclic. Events, albeit with a different spin, repeat themselves. That includes creation, which happens every 5,100 years for the Maya.

The next such event is to happen December 23, 2012, and it is already being heralded in the media as a possible doomsday—excellent fodder for our cataclysmically fixated contemporary culture. I recently asked a Maya daykeeper what was in store for us on that momentous occasion. He said: "It will be a renewal, a rebirth in how we think—there will be peace in the world."

For our native forebears on these shores, numbers had a life of their own, a notion that would never occur to us. Take July 4, 1776. That date gives the number of month cycles (1–12), day cycles (1–30, or 31), and years elapsed since the birthdate of the Christian savior. Unlike Copan's Stela D, it shows no bonding between the numbers and what they represent. We would think it silly if the sevens in our depiction of the year of American Independence bore United States' flags or fireworks popped out of the word "July."

Our numbers are abstract. They are not related to the thing they count, except to give the quantity of it: seven days, seven people, seven bags of groceries. Seven is seven—no more, no less—though like thirteen it retains, for some of us, a veiled meaning from another age when numbers were believed to possess mystical qualities.

We can learn quite a lot about Native American concepts of number by the way people say them. Take the number seven in Quechua, a language spoken today by more than six million descendants of the Inca Empire who live in the high Andes of South America. It is qanchis, thought by anthropologists who have studied the system to represent the image of excess compulsiveness and loutish behavior.

Quanchis acquires this negative quality, informants say, because it is one unit in excess of six, or suqta, which is double the number three, or kinsa, which in turn is considered to be the essence of wholeness and sufficiency. Events, they say, frequently happen in repetitions of three. No wonder the foolish braying burro bellows insistently and excessively: qanchis, qanchis, qanchis ...

The Jivaro of Ecuador and Brazil still use number words that link with the human body; for example five means "I have finished one hand" (wéhe amukei), ten means "I have finished both hands" (mai wéhe amúkahei); fifteen means "I have finished one foot" (huini n‡wi amúkahei), and twenty means "I have finished both feet" (mai n‡wi amúkahei). Six, seven, and eight in Inuit use the term arviniliit, which means "at the edge of the right hand," because they are counted with the little finger, the ring finger, and the middle finger of the right hand. Likewise, the Ojibway words for the same numbers use the term waaswi, which means the same thing.

The habit of retaining the link between quantification and the human body is common among cultures that have no need of tallying massive quantities. A contemporary Maya anthropologist tells the story of two men from a remote area who approach a vendor in the marketplace. "I want me-and-my-brother worth of sacks of dried maize," he says. Translation: forty sacks.Testimony in a lawsuit brought by the Cree Indians of James Bay in Canada against Hydro-Quebéc over a water resource allocation project reflects the role of counting and numbers in native life.

A Cree hunter who appeared as a defense witness was asked: "How many rivers are there in your territory?" The hunter said: "I do not know." The lawyer turned to the judge, thinking he had demonstrated the ignorance of the natives. But because the hunter possessed an intimate knowledge of every kink and bend in every river in his territory, he had no need of knowing how many rivers there were nor even, in numerical terms, the length of each of them.

The point is that we count things when we do not focus on their individual identity, or when there are too many of them to get to know individually. Hunters and gatherers are not ignorant. They do not need the complex kind of mathematical thinking that is a necessity in our society. Take the hunter's tally of a kill of deer or bison carved on a rock in northwestern Mexico and dated approximately to the first millennium. Each dot stands for an animal killed. Here the total count—for the sake of subsistence planning—is all that need be known, that is to say, one animal does not need to be distinguished from the next. Likewise, arithmetic operations such as addition and multiplication of number values of objects started as a shortcut to manipulating the objects themselves.

The Powhatan kept their base-ten tallies on notched sticks and knotted strings. "They count no more but by tennes," Captain John Smith tells us, using words up to a hundred. They also had a word for thousand, but needed nothing beyond that.

One of the main functions of the Native American notched sticks was to keep track of time. A Chippewa woman told a nineteenth-century ethnographer:

When I was young, everything was very systematic. We worked day and night and made the best use of the material we had. My father kept count of the days on a stick. He had a stick long enough to last a year and he always began a new stick in the fall. He cut a big notch for the first day of a new moon and a small notch for each of the other days. I will begin my story at the time he began a new counting stick. [Pointing to the first notch] After my mother had put away the wild rice, maple sugar, and other food we would need during the winter she made some new mats for the sides of the wigwam...

Keepers of calendar sticks are among the most exalted members of the Ojibway tribes, serving as shaman and sky watcher. Other sticks were used to keep track of the number of warriors slain in tribal wars, or the number of skins bartered in a fur trade.

The Inca, fifteenth-century ancestors of today's two million Quechua speakers, kept track of things by tallying their numbers on knotted strings known as quipu, a combination of tactile and visible numeration. Quantity was conveyed by feeling the number of windings on a special knot arrayed from top to bottom on a given string. The base of the system is ten, like our own, with a blank space on the string standing in for zero. There is no number-word for zero in Quechua, probably because numbers for them need to possess "thing," and "nothing" by definition cannot possess anything—therefore it cannot be named. And so, anthropologists tell us, they just say mana kanchu—"there is nothing." Different colors and cord windings on quipus conveyed additional information, perhaps the kinds of things being tallied by the quipucamayoc, or keeper of the strings, for example bushels of potatoes, bales of cotton, or numbers of llama or alpaca.

Sub-cords hanging from main cords, often down to the fifth order, represented lower orders in the count. Some believe quipus were solely intended for accounting, but the system has yet to be deciphered. An intriguing statement by one of the sixteenth-century Spanish chroniclers leaves us wondering whether there was not much more to them: "By the use of his quipu he could read off his history better and faster than a Spaniard with a book...."

Numbers figured in reading the future, too, in native prophecy and fortune-telling. One anthropologist tells of a Maya daykeeper seated at his cardinally oriented table, which is adorned with bowls of incense and lighted candles. He arranges piles of seeds and crystals drawn from his divining bag, adding and subtracting them from one another in an attempt to "borrow from the days" the answers to questions posed by his clients: Will I be cured of the disease which plagues me? Will my daughter's marriage be successfully consummated? Will my crop tide the family over this dry season? For the daykeeper, time is not without content. Nor, as we have learned, is number void without reference to context.

This native intimacy with numbers stands in contrast to Galileo's attack on Pythagoras, who believed that the number three was more perfect than four or two. Galileo said, "These mysteries which caused Pythagoras and his sect to have such veneration for the science of numbers are the follies that abound in the sayings and writings of the vulgar, I do not believe at all."

While we may elevate Galileo to heroic status for helping to erect the foundations of modern science, an enterprise in which number plays a purely descriptive role in relation to physical reality, we also can cite him for his lack of appreciation of a once equally valid and complex world view in which number, like word in the Old Testament, was believed to have a power all its own.

Anthony Aveni is the Russell Colgate Distinguished University Professor of Astronomy, Anthropology, and Native American Studies at Colgate University. Known for his research into Native American archaeoastronomy, he is the author of fifteen books, including The First Americans (Scholastic, 2005), a book for children. He contributed to the winter 2006 journal the story "Telescopes and Almanacs: Colonial Era Astronomy."