Page content

Personable Pooches

by Graham Hood

The Lightfoot House in Colonial Williamsburg's Historic Area, home of Philip Lightfoot II, the likely owner of the dog buttons, below. (Dave Doody, Hans Lorenz)

It has been said that upper-crust Englishmen had more time for their dogs than for their children. Dogs were vital to the rituals of hunting, which were pleasurable; children made demands, which were tiresome. If this was true in England, it must also have applied to some of the colonial American gentry. William Penn, for example, wrote in his Reflexions and Maxims that "men are generally more careful of the breed of their horses and dogs than of their children." I suspect many also thought what it took a Frenchman to articulate: "The more I see of the representatives of the people the more I admire my dogs." Yet references to dogs in colonial Virginia life are as few as those in England in the period are many. So the recent appearance of a set of silver coat buttons, made in the mid-eighteenth century and engraved with individual dogs, evidently commissioned by a scion of Tidewater's Lightfoot family, is noteworthy. Rare and charming, the buttons are humble in their purpose perhaps but afford an unusual glimpse of life and values in colonial Virginia.

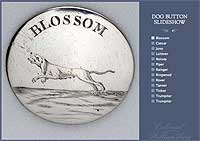

There are thirteen buttons in the set, each one slightly concave and measuring 1 3/8 inches, with a little loop soldered to the back so the button could be sewn to a coat. Each has a maker's mark and the London lion passant for 1739–56. Ten are engraved with a hound running from right to left, seven with its head in the air as if baying. Two show standing dogs, obviously baying. One dog is lying on the ground, its head raised. Each is engraved with the dog's name—Loiterer, which is lying down; Noisey, Ringwood, Rainger, Juno, Tinkerer, Tanner, Caesar, Blossom, Rover, and Piper, which are standing; and two Trumpiters, one running and one standing. They appear to be foxhounds, some of their names allusive, though less saucy perhaps than George Washington's Sweet Lips and True Love.

The last private owner of the buttons, Mary Allen, claimed descent from the Lightfoot family of Sandy Point, Teddington, on the James River, halfway between Richmond and Norfolk. There may have been a portrait of Philip Lightfoot wearing a hunting coat embellished with these buttons, but its location is unknown. Given the date of the buttons, it is likely they were made for Philip Lightfoot II, a prominent merchant and landowner and York County clerk from 1707 until his appointment to His Majesty's Council in 1733. Among his residences was a brick house in Williamsburg, one of the most handsome of the city's surviving structures, which in recent years has housed emperors, kings, presidents, and prime ministers visiting Colonial Williamsburg.

Such a rich and socially prominent man is likely to have run to the hounds as a diversion. He may have participated in the fad of the 1740s of importing a pack of specially bred English foxhounds. Members of the Fairfax family, newly removed to the Northern Neck from England, probably introduced this conspicuous consumerism. Fifty years before, the Rev. John Clayton wrote, Virginians "never Hunt with Hounds ...because there are so many Branches of Rivers, that they cannot follow them. Neither do they keep Grey-hounds, because they say, that they are subject to break their Necks by running against Trees."

We learn from the Colonial Williamsburg publication Colonial Virginians at Play, written by historian Jane Carson in 1965 and since reprinted, that from the colony's early days Virginians hunted game and bred dogs to help them. Though deer were the most prized targets, they were hunted so wantonly that as early as 1705 the General Assembly declared a nine-month closed season on killing them. Practically everything else that moved was fair game, from bears and wolves to possums and squirrels—Vermine Hunting it was called.

Virginians developed local breeds for the purpose and called them Virginia Hounds, then and now. Similar to the English foxhound, the Virginia Hound is a characterful dog. In the early 1970s, soon after my family and I moved into Colonial Williamsburg's Historic Area, a young male Virginia Hound, which looked as if his name could not be anything other than Jack, appeared on our doorstep. He stayed and for twelve years condescended to accept board and lodging with us. He answered to the name of Jack when he chose, chased deer along Francis Street through mid-day traffic, and never let us forget that his first principle in life was "Give me liberty or give me death."

By the mid-eighteenth century, enough land in Virginia was cleared that hunting foxes with packs of dogs was possible, and a smart way to play. By the end of the century, there was fox hunting from the Piedmont to the Eastern Shore. In 1799, a wry New England minister gave a glimpse of the sport:

From about the first of Octor. this amusement begins, and continues till March or April. A party of 10, and to 20, or 30, with double the number of hounds, begins early in the morning, they are all well mounted. They pass thro' groves, Leap fences, cross fields, and steadily pursue, in full chase wherever the hounds lead. At length the fox either buroughs out of their way, or they take him. If they happen to be near, when the hounds seize him, they take him alive, and put him into a bag and keep him for a chase the next day. They then retire in triumph, having obtained a conquest to a place where an Elegant supper is prepared. After feasting themselves, and feeding their prisoner, they retire to their own houses. The next morning they all meet at a place appointed, to give their prisoner another chance for his life. They confine their hounds, and let him out of the bag—away goes Reynard at liberty—after he has escaped half a mile—hounds and all are again in full pursuit, nor will they slack their course thro' the day, unless he is taken. This exercise they pursue day after day, for months together. This diversion is attended by old men, as well as young—but chiefly by married people. I have seen old men, whose heads were white with age, as eager in the chase as a boy of 16. It is perfectly bewitching. The hounds indeed make delightful musick—when they happen to pass near fields, where horses are in pasture, upon hearing the hounds, they immediately begin to caper, Leap the fence and pursue the Chase—frequent instances have occurred, where in leaping the fence, or passing over gullies, or in the woods, the rider has been thrown from his horse, and his brains dashed out, or otherwise killed suddenly. This however never stops the chase—one or two are left to take care of the dead body, and the others pursue.

Fox hunting's popularity translated quickly to the colonies. Here, James Seymour's English Fox Hunting: In Full Cry, circa 1745. (Hans Lorenz)

Noting the phrase "delightful musick" of the hounds, I wonder whether the good reverend knew his Shakespeare. Did he recall the passage from A Midsummer Night's Dream, when Theseus, duke of Athens, tells Hippolyta of "the music of my hounds," "matched in mouth like bells / Each under each. A cry more tunable / Was never holloed to nor cheered with horn"?

Did Philip Lightfoot, I wonder, coursing through Virginia's leafy glades, thrill across oceans and ages to the "musical confusion ...the gallant chiding ...and sweet thunder" of his Trumpiters, his Piper, his Noisey? Modest little things like old buttons can lead to such ruminations.

Another rare piece of Caniniana has recently come to Colonial Williamsburg's collections. In it are linked the leading painter in England of the early and mid-eighteenth century, one of France's great sculptors, and a fledgling English porcelain factory that produced some of the most artistic of wares in this exotic new medium. It touches the hearts of dog lovers everywhere.

William Hogarth is the quintessentially English artist of the eighteenth century. As a young man, he judged that English art had had enough of gods and goddesses and virtuous Romans, as well as too steady a diet of the elite. He had the ability and the stamina to change all that. He portrayed not only the toffs but their hangers-on, retainers and servants, tradesmen and workmen, pimps and whores, beggars and destitute. An engraver, he saw that prints of his paintings would be more affordable across a wide social range. Indeed, they sold well throughout Britain and the colonies. It is fair to guess that by the middle of the century most literate Virginians would at least have recognized his name.

Best known today perhaps are his moralizing series—sets of prints on such themes as The Harlot's Progress, The Rake's Progress, Marriage á-la-mode, and Industry and Idleness. Each print teems with the life of the times, not always wholly literal, but carefully composed for narrative clarity and visual impact. In them, Hogarth shows us some of the idyllic and a lot of the earthy side of the Augustan age. And dogs abound, often urinating, defecating, or copulating—doing the animal things that polite society also did, though mostly behind closed doors. Dogs after all are symbols of the animal self, of natural instincts, of all those things our natures make us want to do before our applied manners exert their constraints.

Painter and pug, Hogarth and hound. William Hogarth's 1745 self-portrait places beast, his pug Trump, before man. (Tate Gallery)

One of three surviving porcelains of Trump, modeled on a terracotta figure by Roubiliac, is owned by Colonial Williamsburg. (Hans Lorenz)

Hogarth had three pet dogs over the years, all pugs, named Pugg, Trump, and Crab. For someone who was described at the time, and is still often characterized, as short and pugnacious, it is typical and symbolic that he had pugs. In 1745, at the height of his career he engraved a self-portrait, a bust-length view of himself in informal dress, with his pug Trump seated on a ledge in front of him.

Prickly and dogmatic, Hogarth was gregarious with other artists. He was one of those "of all Languages and Nations" who gathered at Old Slaughter's Coffee House in St. Martin's Lane, London, in the early 1730s. By the middle of the decade he had revived the St. Martin's Lane Academy, gathering his artist friends there to become a kind of clearing house for, and certainly the greatest influence in the rise of, the Rococo style in England. One of the members of this group was a recent French immigrant, the sculptor Louis François Roubiliac, who sculpted a terracotta bust of Hogarth, revealing "the dogged, fiery little man . . . with an intimacy and remorseless realism."

Presumably about the same time, Roubiliac modeled a terracotta figure of Trump recumbent. Illustrated and identified as early as 1799 as Hogarth's pet fashioned by the sculptor, the clay figure disappeared in the nineteenth century. But soon after it was made it was copied in porcelain, almost certainly through the agency of Nicholas Sprimont, a Huguenot goldsmith and close friend of Roubiliac's family, who took charge of the new Chelsea porcelain factory in the late 1740s. Three examples of this figure, identical in size, are now known, of which Colonial Williamsburg's version is one.

Early Chelsea porcelain is rare and highly collectable. Figural pieces in this soft paste are even rarer, large ones almost as rare as hens' teeth—especially ones that have the living, breathing quality of life about them, as Trump does. Remarkably, the fledgling factory fired a piece of this size without its cracking or warping in the kiln. To walk around this figure is to see a sculptor bringing clay to life. It is more remarkable that this survived the transplant into porcelain. No one who has ever lived with a dog can look at Trump's profile, even more at the back of his head, and not recognize that this is the essence.

The set of engraved silver buttons for Philip Lightfoot is the only one known with a Virginia history. The figure of Trump is one of three. They are rarities indeed, the first of charm, and the second of animation. They are the kinds of things that most museums would treasure, and the kinds of things that surface frequently in Colonial Williamsburg's collections.

Graham Hood, Colonial Williamsburg's vice president for collections and museums and Carlisle H. Humelsine Curator until his retirement in December 1997, writes from his home beside the Chesapeake Bay. He contributed to the spring 2006 journal an article on commemorative cups.

For further reading:

- 18th Century Goes to the Dogs in the Autumn 2004 Journal