A Field Spacious and Untrodden: The Virginian Society for the Promotion of Usefull Knowledge

by Robert Doares

If the capital of Virginia did not shine as a center of scientific endeavor in British North America, it was not for the want of trying by eight individuals who met in Williamsburg in 1772 to organize a forum for gentlemen with inquiring minds. The "Virginian Society for the Promotion of Usefull Knowledge" was likely the brainchild of future patriot and future governor John Page, the most active member of the association. During the four years of its activity, Page's political star rose, but the press of events eclipsed his scientific society, today a curiosity of Virginia history.

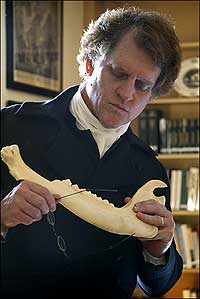

Examining specimens and apparatus, including a vacuum machine, are, from left, interpreters John Barrows, Alex Clark, and Ron Carnegie.

Science had flourished nowhere in America during the seventeenth century. By the 1730s, however, Benjamin Franklin was asking whether America might benefit from a formal organization of the colonies' scientific minds. The first such societies had sprung up in the bustling urban centers of Italy, France, and England in the previous century. By the end of the eighteenth century, they had become indispensable for collecting and publishing scientific knowledge and for encouraging the work of amateurs and professionals. For Americans, the most influential was the Royal Society of London. Chartered by King Charles II in 1662, the Royal Society had an impressive international membership in the 1770s. Its 450 correspondents included eminent scientists and potentates.

In Pennsylvania, in 1743, Franklin, himself a fellow of the Royal Society, initiated the forerunner of what would become the most important scientific society in the early English colonies, the American Philosophical Society. Franklin's organization merged in 1768 with a rival society to form the American Philosophical Society at Philadelphia. The most important scientific workers in America joined, and it soon became the nucleus of scientific activities on the seaboard. Virginians Dr. James McClurg and Dr. Walter Jones were members.

From the 1730s onward, the Virginia Gazette published news of the Royal Society of London, the Royal Academy of Sciences in Paris, the Society for Encouragement of Learning in London, and budding American institutes. Virginia's pattern of rural settlement, however, worked against the establishment of a cohesive scientific community in the colony. Williamsburg was the principal social, cultural, and intellectual center of the Old Dominion, but it could hardly compete with the likes of Philadelphia, Boston, and Charles Town, where a few scientific or medical institutes coalesced. Most Virginians with a scientific bent lived and worked in relative isolation.

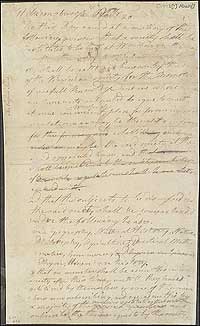

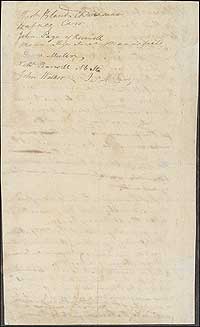

The draft resolution for the Society for the Promotion of Usefull Knowledge, in the Colonial Williamsburg collections.

A notable example was John Clayton, clerk of Gloucester County court. The English-born Clayton formed a close friendship with naturalist Mark Catesby, who worked in Virginia before 1720. Catesby piqued Clayton's interest in natural history, and the clerk soon began a scientific correspondence of his own. Clayton developed a botanical garden and, through introductions by William Byrd II, became well known to members of natural history circles on both sides of the Atlantic. He compiled a highly regarded Flora Virginica, published in Europe by the Dutch botanist Gronovius. Clayton would be the first president of the Virginian Society for the Promotion of Usefull Knowledge.

William Small's scientific society at William and Mary was a forerunner of the society. City of Birmingham Assay Office.

John Page probably fathered the idea for the society and was its most ardent supporter, serving as its second, and last, president. Charles Willson Peale captured his look of friendly curiosity in this portrait. Independence National Historical Park.

Professor of law, mentor to Jefferson and Marshall, signatory to the Declaration, George Wythe promoted the sciences and kept a scientific instruments collection in his home. John Trumbull sketched him in 1791.

The first attempt at forming a scientific society in Virginia was at the College of William and Mary. The college had been a lively center of scientific pursuit between 1758 and 1764, when Dr. William Small, a graduate of the medical college of Glasgow, was professor of mathematics and philosophy. In 1759, Small inaugurated a society modeled upon the new Royal Society of Arts of London. Governor Francis Fauquier lent his prestige to the Williamsburg group, which investigated the medicinal properties of native plants. Young Thomas Jefferson, a student at the college, came under the organization's influence.

In 1766, two years after Small's return to England, Dr. Arthur Lee, member of the Royal Society and a Virginian with a medical degree from Edinburgh, settled at Williamsburg. Lee's two-year residence was too short to revive Small's society. Nevertheless, attention to science, particularly natural science, persisted. Near Williamsburg lived the Carters, Randolphs, Byrds, Lees, Custises, and others with interests in gardening, some of whom corresponded with botanists and nurserymen in Britain. Such men could be counted as prospective members when Page and his seven compatriots started their group November 20, 1772.

A mostly legible rough draft of the resolution produced at the organizational meeting survives in the collections of the John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library at Colonial Williamsburg. The first of the document's three articles called for the institution of a society known as the "Virginian Society for the Promotion of Usefull Knowledge to be held at Williamsburg." The signatories agreed to meet again for "forming such regulations as may be thought necessary to establish the said society." The second section proposed the subjects of inquiry: "Geography, Natural History, Natural Philosophy, Agriculture, Practical Mathematics, Commerce, Physic, American History." The final article stipulated "that no member shall be admitted in society after this time, until they have petitioned by themselves or some of the members now subscribing, and are admitted by a majority of the members constituting this society and subscribe to the terms agreed to by the society."

Besides John Page of Rosewell, burgess from Gloucester County and soon-to-be member of the Governor's Council, the signers of the resolution were: Theodorick Bland, committee chairman; Dabney Carr; Mann Page Jr. of Mannsfield; George Muter; Nathaniel Burwell of Carter's Grove; and physicians John Walker and James McClurg. Burwell, a recent graduate of William and Mary, was the college's first winner of the Botetourt Medal in Natural Philosophy.

The formation of the society was made public in the Virginia Gazette in May of 1773, after its first formal meeting and election of officers. The notice said that a philosophical society of one hundred members had formed "for the Advancement of Useful Knowledge in this Colony." Officers were the botanist John Clayton, president; John Page, vice president; Professor Samuel Henley, secretary; law student St. George Tucker, assistant secretary; and David Jameson, a Yorktown merchant and future Virginia state senator, treasurer. Most of the publicly announced associates of the society had ties to William and Mary. Meetings would be announced in the Virginia Gazette and conducted, for convenience, during sessions of the legislature, when many gentlemen came to the capital anyway.

Not long after the first public announcement of the society, the members published their aims in the newspaper:

The object of their Hopes is to direct the Attention of their Countrymen to the Study of Nature, with a View of multiplying the Advantages that may result from this Source of Improvement.... It is therefore the Intention of this Society to rescue from Oblivion every useful Essay, and they hope that the Efforts of their Members will furnish them with a Collection which may at once both amuse and instruct.... Hence, those who are engaged in different Pursuits may receive from the casual Observation of others such Information respecting their own Inquiries as might otherwise have escaped their Attention.... Virginia furnishes a Field both spacious and mostly untrodden. Who can tell what may accrue to the Inhabitants from an Acquaintance with the Nature and Effects of the Climates and Soils? The minerals, fossils, and Springs, in which the Country abounds, may yield the greatest Emolument both to their owners and the Publick. The Multiplicity of Vegetables and Animals may conduce to the Purposes of Commerce and the Comforts of Life, in Modes with which, at present, we are not acquainted.

Critics suggested Virginians lacked sufficient experience in scientific inquiry to produce concrete results. To counter the argument, an anonymous newspaper essayist, "Academicus," enumerated the accomplishments of earlier such societies and pointed to potential benefits of immediate consequence to Virginians in areas such as agriculture, commerce, navigation, and natural history. He highlighted the isolation of gentlemen with scientific interests and argued the need for centralized collection and publication of scientific findings. The author chastised Virginians for their economic dependence on the staple tobacco, with its disastrous effect on agriculture. He saw the most promise for practical contributions by the gentlemen planters of Virginia in the improvement of agriculture. Noting Virginia's lack of cities, he said that planters could at least "make Experiments in Agriculture, without Detriment to the usual course of their business."

For a time, the Society for the Promotion of Usefull Knowledge commanded much attention. Lord Dunmore, the royal governor, assumed the post of patron. The hundred Virginians who joined, "in humble imitation of the Royal Society," seemed ready to support the promotion of any useful knowledge that might benefit their sagging economy.

The organization met regularly in its first year, as evidenced by frequent newspaper calls for meetings at the Capitol. At the beginning of the society's second year, after the death of John Clayton, members elected new officers: John Page, president; jurist George Wythe, who kept scientific instruments in his home, vice president; Professor James Madison, and the Reverend Robert Andrews "of York," secretaries; David Jameson, treasurer; and Madison, curator. The society also elected corresponding members, among them Benjamin Franklin and Dr. Benjamin Rush from the Philadelphia society, a Marylander, and Englishmen.

At this meeting, members awarded a monetary prize and gold medal to John Hobday for the invention of a "most ingenious threshing machine." Called a "cheap and simple" device, it could thresh 120 bushels of wheat in three days and could be replicated cheaply. In his study Science in the Virginia Gazette, 1736-1780, Richard Overfield says this was the first medal awarded by an American scientific society for a practical invention. It is the Virginia society's only concrete evidence of accomplishment. Hobday's invention was older than the society and was perhaps the catalyst for its establishment. In 1772, John Page had sought subscribers to finance the distribution of models of Hobday's machine.

During its life, the society collected a few papers, meteorological journals, and other observations. It generated some useful information published in the newspaper, such as a Virginia planter's description of a lightning strike on his house and his treatment of slaves who suffered injuries from it. By 1775, though, the fledgling group was struggling with its own relevance in the midst of war.

In May of 1777, on the fourth anniversary of the founding, John Page acknowledged the society's decline in the Virginia Gazette. It had not met for two years because of the "critical situation of our country and the difficulty of convening so large a number of members as were required to constitute a meeting." The officers decided that a committee of seven, with the president or vice president, should carry on the business of the organization. Calling for submissions of observations for a printed journal and further gifts of specimens for the formation of a "cabinet" or museum, Page reaffirmed the importance of the sciences in support of "all the arts and manufactures we are now so much in need of... which never more require their assistance and attention than in the present situation of America."

Page's appeal rallied none of his fellows from their preoccupations with war and politics, and he, too, entered the fray. The Virginian Society for the Promotion of Usefull Knowledge never revived.

ADDITIONAL IMAGES

Bob Doares's story "Tailoring the Tenant House" appeared in the winter 2002-2003 issue of the journal. Doares is an instructor in Colonial Williamsburg's department of Historic Area training.