John Hope circa 1732 — ?

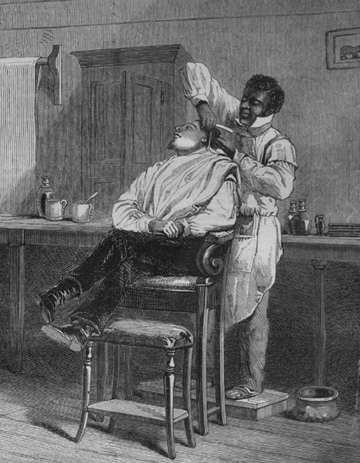

At about the age of ten, John Hope a.k.a. Barber Caesar, became a victim of the transatlantic slave trade when he was captured and sold in Virginia, in North America, in 1742. He was sold to Benjamin Catton of Yorktown and given the slave name of Caesar. Catton brought the frightened young man before the York County justices to have his age determined for tax purposes. In addition to operating a tavern, Catton hired men from London to make wigs. He also advertised the sale of hair and haircuts for men and women. Caesar may have learned his barber skills from his owner or other workers in the establishment.

After Catton’s death in 1749, his son, Doctor Benjamin Catton Jr., inherited Caesar as his slave. Following Dr. Catton’s death in 1768, Dr. Riddell purchased Caesar for £150, which indicates that Caesar possessed highly valuable skills. Apparently, Caesar’s barbering skills and character were exceptional. His occupation exposed him to important conversations among gentlemen of the gentry class.

In 1775, on the eve of the American Revolution, Virginia Governor Lord Dunmore attempted to restore order in the colony by declaring martial law and issuing a proclamation that offered freedom to slaves belonging to rebel (American Patriot) masters who joined the British cause. To discourage enslaved people from joining the British forces, the Patriots used the Virginia Gazette newspapers to emphasize that Dunmore’s promise of freedom could not be trusted. The newspaper featured an interview with “Caesar, the famous barber of York.” The interviewer asked Caesar, described as “An honest negro,” about Dunmore’s proclamation. Caesar replied that “he did not know anyone foolish enough to believe him, for if he intended to do so, he ought to first to set his own free.” Beyond his words, his actions demonstrated loyalty to the Patriot cause. A legend survived after the war which indicated that Barber Caesar acted as a spy, when he provided false information to the British gentlemen he was barbering.

When Dr. Riddell died in 1779, his wife Susanna Riddell inherited all of his enslaved property. Later that year, Susanna petitioned the Virginia Assembly to free Caesar. The General Assembly had only approved about a dozen manumission petitions since 1723. Her petition was joined by the signatures of at least thirty-two residents of Yorktown in support of Caesar’s freedom.

Now a free man, Caesar—calling himself John Hope—appeared on the Williamsburg 1784 tax lists, paying taxes on himself and two black males, including his son Aberdeen, whom he purchased from Hugh Nelson in 1783. Without manumission papers, Aberdeen was legally John’s slave. Fortunately, a new manumission law passed in 1782, allowing John to free his son.

John Hope sought new clientele when he moved to the new Virginia capital, Richmond. The 1787 tax records identify him by the name of Caesar and his occupation as a barber. In addition to paying taxes on himself and a horse, he paid taxes on four black males under the age of sixteen. During the 1790s, Hope purchased a lot on Shockoe Hill, just a few blocks west of the Capitol building.

Records indicate that the number of blacks in Hope’s household fluctuated through the years. It is possible that some of the people in his household were either family or apprentices. He had, for example, an enslaved apprentice who ran away with some tools. Hope also appeared in newspaper advertisements and on the Richmond City property tax list, as he accumulated a lot, home, stable, and garden.

John married another enslaved woman and had two children with her. His daughter, Judith, later petitioned the legislature for her freedom. She claimed that her father had requested his executor, Edmund Randolph, “to purchase with a portion of the estate both your petitioner and her brother, and to have them emancipated.” Randolph may have been unable to carry out this wish before dying in 1813, or perhaps he refused to honor John Hope’s request. Clearly, Hope was unable to purchase the freedom and manumit his children before he died.

John Hope, or Barber Caesar, was part of a long tradition of black barbers in the Atlantic world who exclusively served white male clientele. The tradition continued into the twentieth century in the United States. Barbering skills allowed a ten-year-old African boy access to some of the most powerful and influential gentlemen of his time. His mastery of European genteel society afforded him a means to earn a living and motivated his mistress to petition for his freedom. His fame as the “Barber Caesar of York” permitted him to raise a family and to own property. It is also possible that Hope secretly supported the free black and slave community throughout his life by passing along information or “intelligence” gleaned from the conversations he overheard among his white male clientele.